A deep record of unknown hominins from Sulawesi

A cave known as Leang Bulu Bettue provides a record from the Middle Pleistocene across the arrival of modern people.

Sulawesi has become one of the most exciting areas for discoveries in human evolution. Last year, archaeologists led by Budianto Hakim showed that hominins have been on the island for at least a million years—although whether continuously or intermittently is not clear.

Unknown also is who the first inhabitants were. Maybe they were descendants of the Homo erectus population that inhabited Sundaland from 1.5 million years ago or earlier. Without fossils we cannot be certain.

The earliest skeletal evidence of hominins from the island is vastly younger, a mere 25,000 to 16,000 years old. A fragmentary upper jaw of a modern person of this date comes from a cave called Leang Bulu Bettue, near Maros in south Sulawesi.

This cave has been heating up for the last decade as excavations reach deeper into the its sediment floor.

In an open access paper from late 2025, Basran Burhan and collaborators give the first report of much earlier finds from the deepest-known layers of Leang Bulu Bettue. The oldest artifacts they report come from between 208,000 and 132,000 years ago. They make Leang Bulu Bettue the first site on Sulawesi with a record spanning from the Middle Pleistocene across the arrival of early modern people.

Such a record has high value. It may reveal what happened to the earlier inhabitants. Comparable sites in the region are Callao Cave, on Luzon, and Liang Bua on Flores—both showing evidence of an early island hominin species followed by modern humans.

Leang Bulu Bettue

The Leang Bulu Bettue cave has a long tunnel leading from a rockshelter entrance at the base of a cliff. The researchers note that the cave’s name in the Bugis language means roughly “cave of the tunnel through the hill”. It sits within the highly karstic landscape of the Maros regency, where steep, narrow valleys cut between tall, isolated towers of limestone.

The cave is near some of the earliest figurative rock art in the world, dated to more than 50,000 years ago, at Leang Karampuang and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4.

Many of the finds from later, higher levels in the cave have been previously reported in other papers. Those include:

Rock art on the cave’s ceiling, including hand stencils, apparently dating to a similar period as art from nearby sites like Leang Karampuang. These are overlain by black pigment drawings from the era when Austronesian language-speaking people lived on the island, a few thousand years ago.

A modern human bone fragment, Maros-LBB-1a: the right half of a maxilla with three molars, from layer 4a of the site with an age estimated between 25,000 and 16,000 years ago.

Layers dating to between 30,000 and 22,000 years have ochre blocks, animal bone with traces of ochre, and a few artifacts that were personal ornaments or part of the production chain for ornaments. These may show some of the portable components of the art tradition reflected by cave paintings.

In the new study, Burhan and coworkers probe more deeply. The rich and dense record of the last 40,000 years becomes spotty and intermittent going further back.

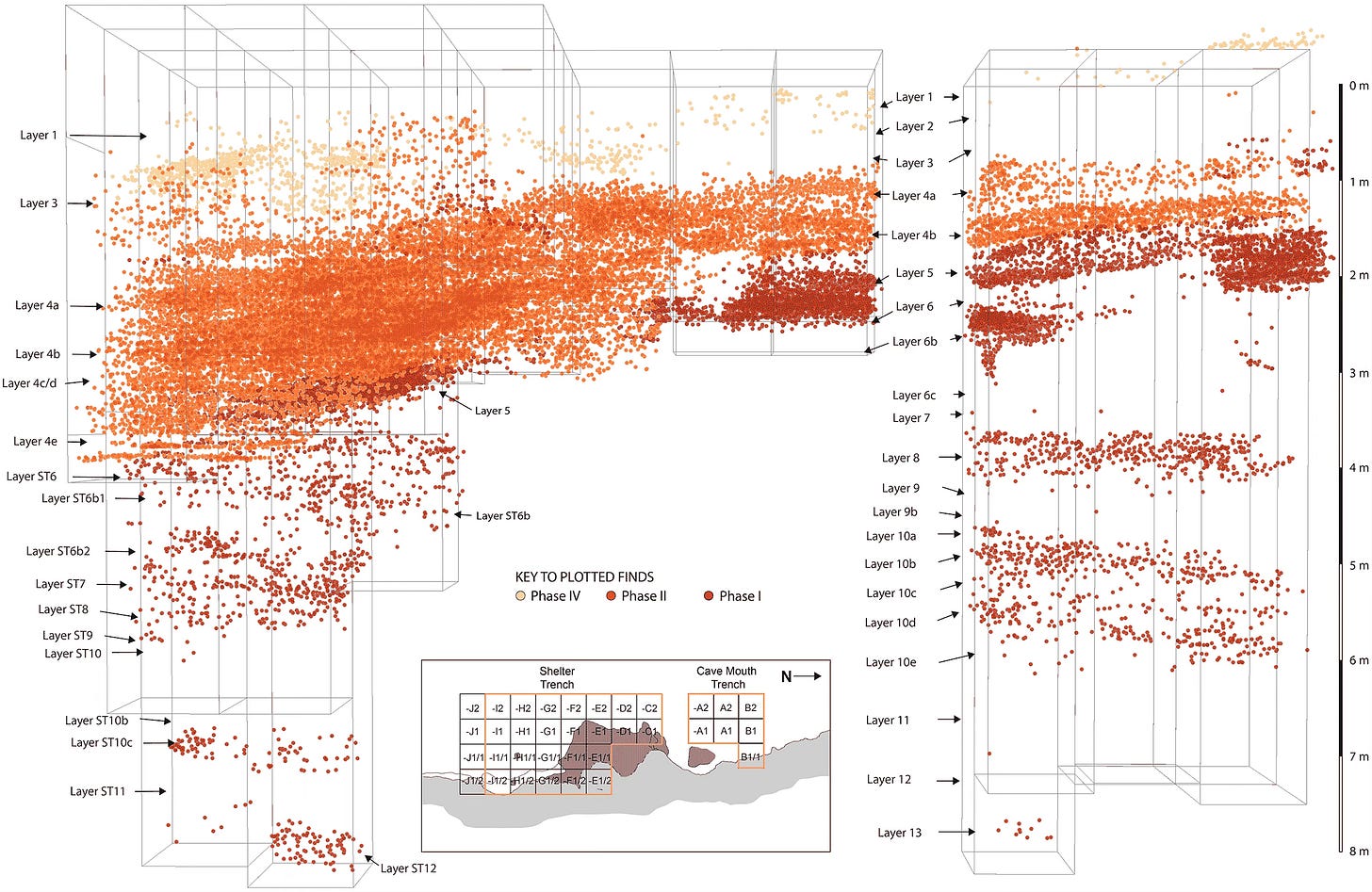

In the paper is a great figure showing the spatial distribution of artifacts, bone, and other objects plotted throughout their two excavation areas. The finds plotted in yellow come from Austronesian culture and Neolithic periods, all within the last few thousand years. The orange dots represent finds from the period between 40,000 and 16,000 years ago, which Burhan and coworkers denote as “Phase II”, while the darker red dots represent “Phase I” finds in layer 5 of the site and below, all older than 40,000 years.

The finds reaching back to lowest parts of the excavation are older than 132,000 years. Clearly a key time in the site’s history is the intensification of site use that started around 40,000 years ago.

A tale of two industries

In an earlier paper led by Yinika Perston in 2022, working from the higher layers, the team could already see that something different was happening before 40,000 years ago.

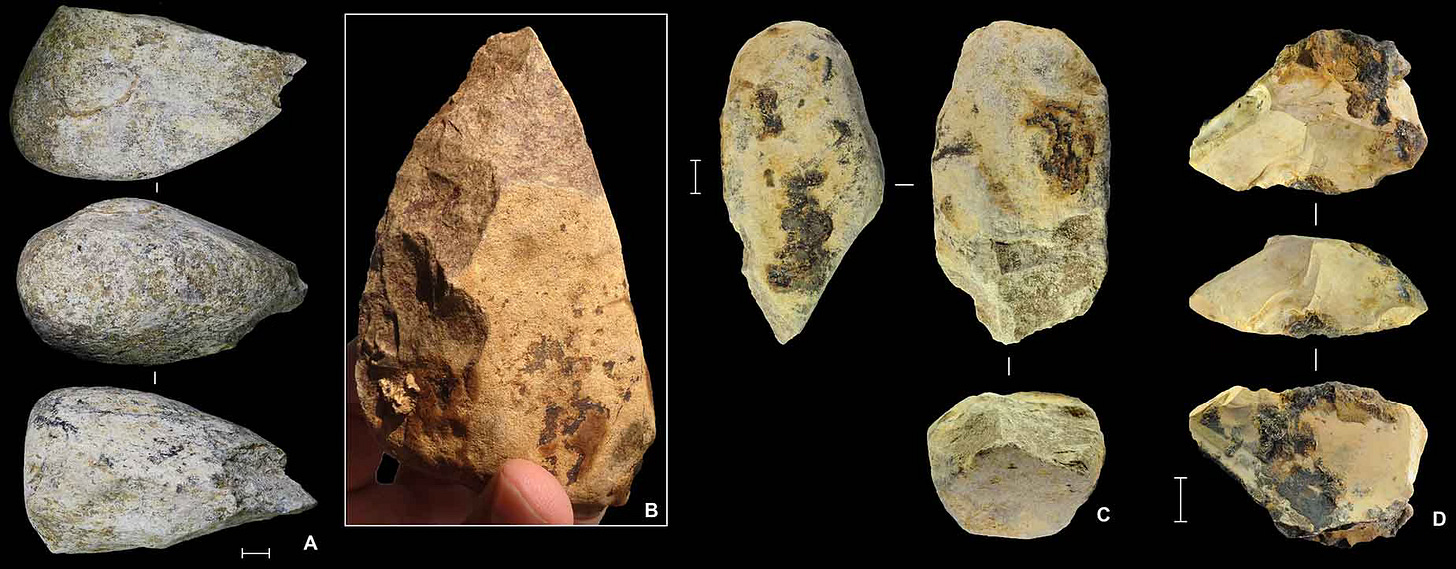

An “Upper Industry” after 40,000 years ago includes many large, elongated flakes and many microblades. Some of the artifacts are coated with patches of ochre residue, and some are shaped in ways that suggest specialized processing of ochre. The toolmakers of this period used several different flaking methods. Their tools were mostly made from chert, often brought to the site from outside the immediate local area.

The “Lower Industry”—at the time known mainly from layer 5—includes large cores, some flaked from limestone and some made from volcanic stream-rolled cobbles. Nearly all the artifacts are locally available materials, and chert is rare.

The recent study from Burhan and coworkers extends that record substantially deeper into the site. Even so, the Lower Industry in layers 5 and below have only 40 artifacts, compared to more than 25,000 artifacts excavated from layer 4 alone. The current evidence shows that Lower Industry artifacts from Leang Bulu Bettue go back to layer 10, with an estimated age between 208,000 and 132,000 years.

The difference between Lower and Upper industries looks like a cultural break. The tools from the Lower Industry are not only limited in their flaking processes and raw material sources, they reflect a vastly less intensive use of the cave than the Upper Industry.

Perston and coworkers observed that 40,000 years ago is close to the first arrival of modern humans in the region, who were likely the makers of the Upper Industry. The Lower Industry, on the other hand, was likely produced by earlier hominins.

Who were the earlier inhabitants?

Burhan and coworkers note that stone artifacts from Talepu, also in south Sulawesi, are in the same time range and similar in their manufacture. A decade ago, Gerrit van den Bergh and coworkers sunk a deep trench there, finding artifacts more than two meters down, in sediments estimated between 194,000 and 118,000 years old. The artifacts belong to a flake and core industry made from river cobbles and targeted toward production of sharp edges without much shaping or retouching. They resemble the Lower Industry tools from Leang Bulu Bettue.

Who made these tools? There are several possibilities.

Maybe Denisovans reached the island, accounting for their strong legacy within the genomes of people in the Philippines, Papua, and the surrounding area.

Maybe Homo erectus was present on the island. This species certainly existed on Java around a million years ago, the time the first evidence of habitation of Sulawesi is recorded. Sulawesi is a large enough island that a population of H. erectus might have persisted there without necessarily changing much from the earliest inhabitants.

When the island was inhabited a million years ago, possibly by H. erectus, the population may have adapted to local circumstances. If that adaptation went far enough, it may have become an endemic island species along the lines of Homo luzonensis or Homo floresiensis. On a larger island than either Flores or Luzon, its characteristics might look very different from those other hominins.

I wish the stone tools gave more of a clue. But nothing in the cultural evidence gives me a reason to prefer one of these hypotheses over the others.

Cutmarks

One thing I want to highlight briefly is that Leang Bulu Bettue has evidence for cutmarks on animal bones in a lower level than any stone artifacts have yet been identified. In layer 13 of the Cave Mouth Trench portion of their excavation, Burhan and collaborators found four bones with marks from butchery by sharp artifacts: two macaque bones, a bone from an anoa (dwarf buffalo), and an unidentifiable bone fragment. These are older than any stone artifact in the site.

This isn’t strange. The overall intensity of cave use during the Phase I period was very light. Flaking debitage is mostly absent, which means tools of the Lower Industry were mostly not made in the cave. Hominins that carried tools in would usually have carried them back out. Meanwhile, they may have processed animal carcasses outside the cave, only carrying parts inside occasionally. Or in some instances, animal scavengers might move parts of butchered carcasses into a cave opening.

What makes me point to the early cutmarks is that they are part of a larger statistical pattern. The first evidence of hominin presence in many sites—and in some entire regions of the planet—is cutmarked bone.

Of course the Leang Bulu Bettue evidence is not the earliest occupation evidence on Sulawesi. The stone tools from Calio, in the Walanae valley, show that toolmakers got their start on the island by 1.26 ± 0.22 million years ago. This was one of the biggest stories in human evolution that I reviewed in 2025.

In a region where individual hominins may have made thousands of artifacts in their lives, and butchered thousands of animals, both kinds of traces may vastly outnumber the skeletal and dental remains of hominins themselves. But which comes first? The answer may depend what kind of sites archaeologists happen to investigate.

Probing a mismatch

Readers will probably notice what stood out to me in these papers. If rock art at nearby sites is now dated to more than 50,000 years ago, why is the threshold dividing occupation phases reflected in the sediments at Leang Bulu Bettue only 40,000 years old?

Maybe some disconnect is to be expected. Rock art may have been such a part of the lives of the early coastal travelers that people left marks long before actually settling on Sulawesi. It’s clear from the early archaeological record of Australia that pigments and marking were important part of cultures from their arrival. Possibly across the region, paintings tied together the places travelers had been long before new populations grew to densities where a cave like Leang Bulu Bettue would get much use.

Still, the persistence of the Lower Industry into the period after 50,000 years is curious. These artifacts are so few, so differently made than later stone tools. Is it possible that the earlier hominin inhabitants of Sulawesi persisted for up to 10,000 years after the first arrival of modern people? The cave record seems to suggest not only did those hominins survive, they were dominant in their presence in Leang Bulu Bettue, only a stone’s throw from the Leang Karampuang paintings.

My sense is that cultural interchange should have been much more likely than isolation. Earlier publications on Leang Bulu Bettue have emphasized the connections between the wider regional rock art and the evidence for ochre and portable art in the cave. If something impeded such interchange for 10,000 years, I want to understand how.

References

Aubert, M., Brumm, A., Ramli, M., Sutikna, T., Saptomo, E. W., Hakim, B., Morwood, M. J., Van Den Bergh, G. D., Kinsley, L., & Dosseto, A. (2014). Pleistocene cave art from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Nature, 514(7521), 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13422

Brumm, A., Bulbeck, D., Hakim, B., Burhan, B., Oktaviana, A. A., Sumantri, I., Zhao, J., Aubert, M., Sardi, R., McGahan, D., Saiful, A. M., Adhityatama, S., & Kaifu, Y. (2021). Skeletal remains of a Pleistocene modern human (Homo sapiens) from Sulawesi. PLOS ONE, 16(9), e0257273. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257273

Brumm, A., Hakim, B., Ramli, M., Aubert, M., Van Den Bergh, G. D., Li, B., Burhan, B., Saiful, A. M., Siagian, L., Sardi, R., Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Mubarak, A. P., Moore, M. W., Roberts, R. G., Zhao, J., McGahan, D., Jones, B. G., Perston, Y., … Morwood, M. J. (2018). A reassessment of the early archaeological record at Leang Burung 2, a Late Pleistocene rock-shelter site on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0193025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193025

Brumm, A., Langley, M. C., Moore, M. W., Hakim, B., Ramli, M., Sumantri, I., Burhan, B., Saiful, A. M., Siagian, L., Suryatman, Sardi, R., Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Mubarak, A. P., Hasliana, Hasrianti, Oktaviana, A. A., Adhityatama, S., Van Den Bergh, G. D., … Grün, R. (2017). Early human symbolic behavior in the Late Pleistocene of Wallacea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(16), 4105–4110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619013114

Burhan, B., Hakim, B., Sumantri, I., Suryatman, Saiful, A. M., Oktaviana, A. A., Sardi, R., Hasliana, Ramli, M., Siagian, L., Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Syahdar, F. A., Hamrullah, Ilyas, I., Muhammad, P. H., Budi, S. S., Djindar, N. I., Adhityatama, S., … Brumm, A. (2025). A near-continuous archaeological record of Pleistocene human occupation at Leang Bulu Bettue, Sulawesi, Indonesia. PLOS One, 20(12), e0337993. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0337993

Hakim, B., Wibowo, U. P., van den Bergh, G. D., Yurnaldi, D., Joannes-Boyau, R., Duli, A., Suryatman, Sardi, R., Nurani, I. A., Puspaningrum, M. R., Mahmud, I., Haris, A., Anshari, K. A., Saiful, A. M., Arman Bungaran, P., Adhityatama, S., Muhammad, P. H., Akib, A., Somba, N., … Brumm, A. (2025). Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene. Nature, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6

Perston, Y. L., Moore, M. W., Suryatman, N. F. N., Burhan, B., Hakim, B., Hasliana, N. F. N., Agus Oktaviana, A., Lebe, R., Mahmud, I., & Brumm, A. (2022). Stone‐flaking technology at Leang Bulu Bettue, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Archaeology in Oceania, 57(3), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/arco.5272

van den Bergh, G. D., Li, B., Brumm, A., Grün, R., Yurnaldi, D., Moore, M. W., Kurniawan, I., Setiawan, R., Aziz, F., Roberts, R. G., Suyono, Storey, M., Setiabudi, E., & Morwood, M. J. (2016). Earliest hominin occupation of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Nature, 529(7585), 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16448