Bizarre foods: Neanderthal edition

Scientists propose a maggot-fueled hypothesis for the diets of ancient hunters

New research out this week suggests that Neanderthals may have been like many recent hunting societies that eat their meat aged. Well, to be perfectly candid, “aged” in this context means slimy and maggot-ridden.

This is the sort of thing that makes me love paleoanthropology.

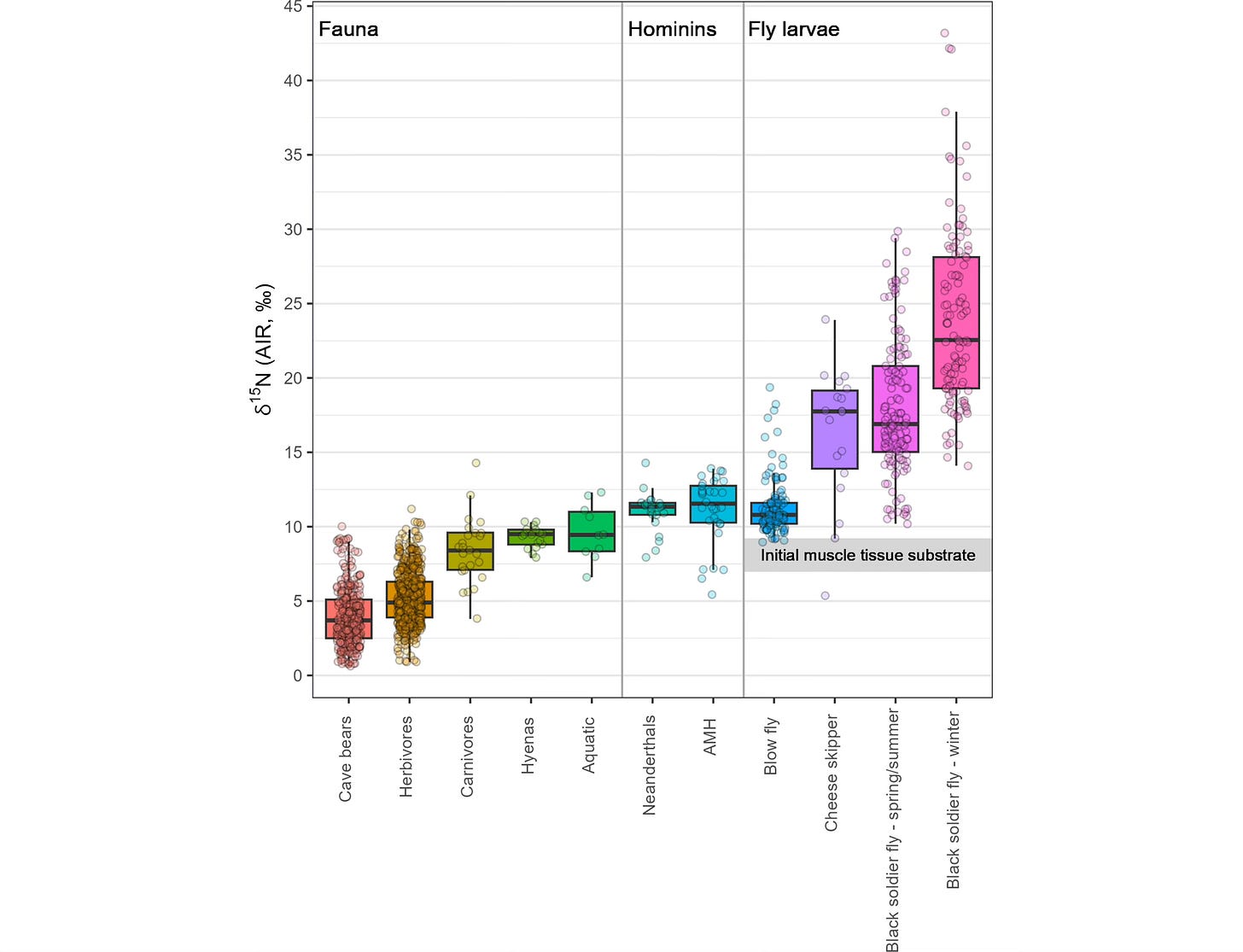

The research, from Melanie Beasley, Julie Lesnik, and John Speth, set out to solve a conundrum related to nitrogen stable isotopes in Neanderthal bone collagen. How can ancient humans end up with bone chemistry that makes them look more carnivorous than hyenas or wolves?

Beasley and coworkers point to one possible solution that had been overlooked: insects.

Taking a 2017 article by Speth as a starting point, they looked at customs of hunter-gatherers around the world who eat meat that has begun to undergo fermentation or putrifaction.

“Indigenous peoples almost universally viewed thoroughly putrefied, maggot-infested animal foods as highly desirable fare, not starvation rations.”—Melanie Beasley, Julie Lesnik, and John Speth

Old meat gathers fly larvae, fly larvae convert lean fat-poor mammal meat into fat-rich maggot meat, Neanderthals win. Maybe this seems like a stomach-turning story. But Beasley, Lesnik, and Speth find that stable isotope biology supports the idea of putrifaction and maggot attraction, which—as they memorably relate—is part of the diets of many historic and current groups around the world.

The road to hypercarnivory

Chemistry reflects an animal’s place in the food chain in various ways. One of the most visible is nitrogen, which all animals obtain from their food, incorporating some into their proteins and excreting the rest as urea. Nitrogen-14 is the most common form in nature. The alternative isotope nitrogen-15 is stable but makes up under 0.4% of atmospheric nitrogen. Animals excrete a slightly higher proportion of nitrogen-14 in their urine than they take in, and this tends to concentrate nitrogen-15 slightly in their tissues.

Nitrogen-15 thus tends to percolate up the food chain. Animals have more than plants; carnivores more than herbivores.

By now more than twenty years of results from nitrogen isotope sampling of Neanderthal skeletal remains has shown a consistent result: Neanderthals had a higher fraction of nitrogen-15 than most of the other mammals in their environments. Neanderthals average even more nitrogen-15 in their bone collagen than most carnivores.

On this basis many researchers have argued that Neanderthals were hypercarnivores, with their protein derived almost exclusively from eating meat.

When the first stable isotope results from Neanderthals were being published in the late 1990s, finding evidence of hypercarnivory seemed like a triumph. From the nineteenth century into the 1960s, archaeologists had understood Neanderthals to be hunters. But archaeologists led by Lewis Binford from the 1960s into the 1990s championed an attitude of skepticism of all early hunting evidence.

Binford and others also argued that the hunting implements known to have been used by Neanderthals, especially thrusting spears, were not suitable for effective and routine hunting. They also voiced skepticism that broken and burned bones of prey animals found at most sites were hunted. Many faunal remains, in their view, could have resulted from opportunistic scavenging and “power scavenging” by driving predators away from kills.

So the stable isotope results seemed to confirm that the Neanderthals were not so clueless as Binford had suggested. They had primary and reliable access to large mammal prey.

Yet with Neanderthals, I find that almost every win is secretly a loss. That turned out to be the case with hypercarnivory. Traditional hunters in temperate climates tend to eat more of a balance of plant foods in combination with meat. If Neanderthals relied so strongly on hunted meat, some suggested, they may have been incompetent at foraging for plant foods. One thing everyone seemed to agree on: Neanderthals were weird.

Is hypercarnivory a myth?

Archaeologists now have a lot of evidence that Neanderthals ate a wide range of plant foods. That evidence comes from direct microfossils of plants in Neanderthal dental calculus, from charred bits of cooked plant foods in Neanderthal fires, and in at least one case, from the chemistry of Neanderthal fecal material. It’s tough to say how much of the caloric intake of Neanderthals came from plant foods, but clearly most Neanderthals knew and used a wide range of plants.

If they ate plants, why did Neanderthals’ nitrogen isotopes look like hypercarnivores? How would that dietary strategy even work?

Some of the first detailed considerations of the importance of fat and carbohydrates in the diets of ancient hunters were provided by John Speth himself more than thirty years ago, and the basic math has not changed. Lions and wolves have the metabolic equipment to subsist almost exclusively on meat from lean, wild animals, but humans don’t. Even people today who are seeking to lose weight on a carb-free “keto diet” need to take in fat with their protein, and lean meat from wild hunted animals often lacks sufficient fat.

Only societies in Arctic landscapes really fit the hypercarnivore niche among contemporary hunter-gatherers, and those societies rely upon marine mammals with year-round blubber, not the lean terrestrial prey species that Neanderthals mostly hunted.

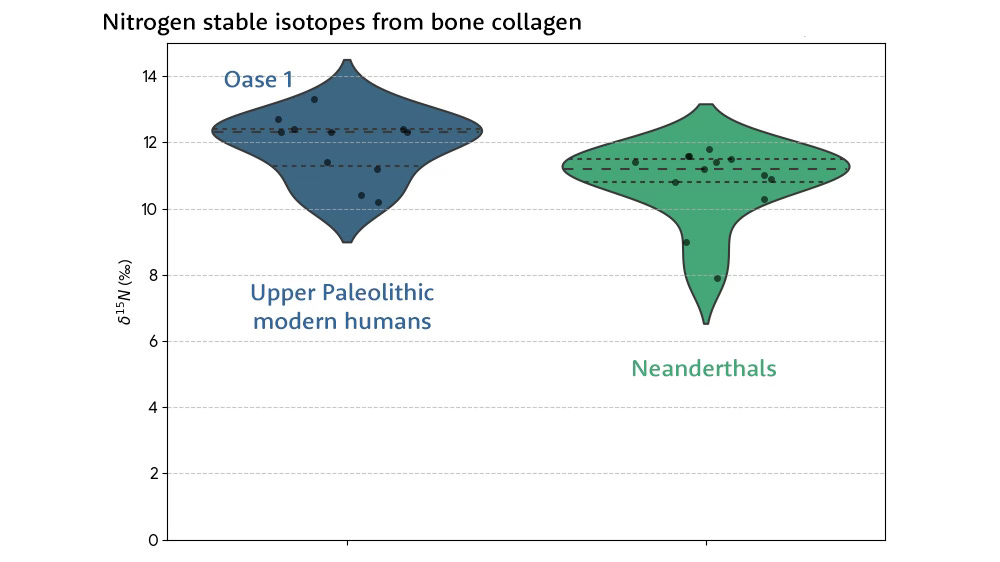

For me, a central observation is that it’s not just Neanderthals that look like hypercarnivores. In 2009, Michael Richards and Erik Trinkaus provided one of the first large-scale comparisons of Neanderthal collagen stable isotopes with the people who immediately followed them in Upper Paleolithic times. They confirmed that Neanderthal nitrogen-15 values look like top-level carnivores. At the same time they found that the Upper Paleolithic-associated people were even more extreme.

The highest value of nitrogen-15 found by Richards and Trinkaus was from the Oase 1 mandible, representing an individual who lived around 40,000 years ago in Romania. We know today from the ancient genome of Oase 1 that this individual was a fifth or sixth generation descendant of at least one Neanderthal, with around to 10% Neanderthal genetic ancestry. He happened to belong to a group that had little or no input into today’s European people. And his collagen had more nitrogen-15 content than the most extreme wolves and hyenas.

Oase 1 is the highest of the Upper Paleolithic-associated humans, but not out of step with the others. Richards and Trinkaus suggested that aquatic foods such as freshwater fish might explain their high nitrogen-15 values. Aquatic food chains tend to be longer than terrestrial ones, so that medium- and large-sized fish often have higher nitrogen-15 than land carnivores.

It’s never been clear to me why aquatic foods are not considered more often as part of the Neanderthal diet. Use of fish and marine mammals has been documented in sites from Gibraltar, Italy, and France—reviewed well by Bruce Hardy and Marie-Hélène Moncel in a 2011 paper. Fish tend to be less visible in the archaeological record of caves and rockshelters than large herbivores, because a person who catches a fish doesn’t tend to be transport it back to the cave, and often eats it raw. Freshwater fish can be caught by hand in shallow streams, a job that can be aided substantially by the construction of simple weirs. Birds that eat aquatic species, too, may have been part of many Neanderthals’ diets.

Eating foods of aquatic origin would make the nitrogen stable isotope measures less relevant as a measure of overall meat versus plant consumption. But as a dietary strategy, aquatic foods certainly make a great deal of sense even for people who eat a very high fraction of meat.

So frankly I’m bullish on the idea that fish, crayfish, and other aquatic species were eaten commonly enough by Neanderthals to make a difference to their nitrogen stable isotopes.

But aquatic foods are not the only game in town.

Adding insects

Nitrogen stable isotope values for insects are hugely variable, not surprising considering the varied diets and positions in the trophic hierarchy of different kinds of insects. As I reviewed papers, I was fascinated to see that the honeybees of some regions have nitrogen-15 values comparable to mammalian carnivores—making bee brood a possible source of nitrogen-15 enrichment for both humans and other species that eat them, including brown bears.

Compared to most insects, carrion-eating fly larvae have a head start. Their food is enriched in nitrogen-15 compared to plants, and they build up an increased level of the isotope as they feed on the meat. Maggots came to Speth’s attention as he examined the historical and ethnographic descriptions of meat-eating from hunters in Siberia, North America, and other parts of the world.

I can write nothing that could compare with the vivid descriptions of these foods in Speth’s articles, including the open-access 2017 article in PaleoAnthropology and the new article with Beasley and Lesnik.

“[C]ounterintuitive as it may seem, even meat that is so putrid that it literally reeks and is filled with maggots may nonetheless be perfectly safe to eat, the smell notwithstanding. In other words, just because meat is putrid does not mean it contains unsafe levels of pathogens—‘putrid’ and ‘pathogenic’ are not synonymous. And as will become eminently clear in what follows, many, perhaps most, northern foragers, at least until quite recently, actually considered foods in just that sort of thoroughly putrefied state—maggots and all—as rewarding and delicious. And they appear to have been utterly unfazed by odors that would almost certainly trigger an instant gag reflex among most Westerners.”—John Speth

In the new article, the authors discuss situations where drying meat on racks yields abundant infestations of maggots that are themselves gathered and eaten. In other situations, parasitic fly larvae that live within the hides of prey animals are eaten—“fat and salty, a spring treat”.

An observation that cross-cuts many of these stories is that societies that live on hunting and fishing wild foods often prize the taste of meat that has fermented or putrified. There’s nothing too odd about this. Tastes vary. An interesting aspect of the examples is that they are means of extending the value of a kill over a longer period of time.

Dead mammoths

Possibly the largest meat resource available to Neanderthals and many other ancient humans were megafaunal carcasses. In Eurasia, mammoths, straight-tusked elephants, and rhinoceros existed in large numbers.

There is substantial evidence for hunting of these megafauna by Neanderthals and by earlier hominins. In the early days of stable isotope studies, Hervé Bocherens and coworkers suggested that mammoth meat—itself somewhat enriched in nitrogen-15 compared to other herbivores—was a likely explanation for what they were finding in Neanderthal bone collagen.

In the years since then, Ran Barkai and collaborators have written a great deal about the importance of elephants as a prey species for Middle Pleistocene hominins. A good open-access paper describing their ideas was led by Miki Ben-Dor in 2011, titled “Man the Fat Hunter”.

Putrifying meat comes into the description of hunting societies in another way: People often made use of whale carcasses, which could remain viable sometimes for weeks after a hunt. For example, Charles Willoughby in 1886 described the diet of the Quinault, including details about whale beachings.

“Any putrid flesh that floats ashore is eagerly devoured. The beaching of a whale creates the greatest excitement, and the largest amount possible of the decaying blubber is secured to be eaten or dried for future use.”

Imagine the spring thaw in Pleistocene Europe and Central Asia when mammoth carcasses and other large mammals emerged from ponds and rivers. Many, including Clive Gamble, have written about the utility of fire in helping make chilled and frozen meat from the large carcasses available to Paleolithic hunters. But nearly all who have written about megafaunal consumption have emphasized that meat will spoil rapidly.

As Beasley, Lesnik, and Speth reflect, stinking meat may not be spoiled. Large megafaunal carcasses can be valuable for weeks when defended from scavengers. The insect life that inevitably colonized such carcasses would have been a valuable nutritional resource for ancient people. Drying great strips of elephant flesh, even partially or imperfectly, would elongate the utility of the carcass and attract maggots that might have more nutritional value than the meat.

Final thoughts

The struggle interpreting the stable isotope data is a fundamental challenge of overdetermination. There are really only a small number of measurements researchers can take on any individual, and many different combinations of foods that might be part of ancient diets. That means the equation has many more possible solutions than the data can test.

I was reading some online comments about the fly larvae story, and one person suggested it is a great story, if only there were some proof. That’s a common refrain with studies of ancient behavior.

“Neanderthals are not dietarily special as a hominin. But hominins are dietarily special as an omnivore who processes, stores, smokes, salts, putrefies, leaches, mixes foods with nonfood substances, and cooks.”—Melanie Beasley, Julie Lesnik, and John Speth

I like the idea that putrifaction of food was one of many factors influencing the nitrogen stable isotopes of ancient people. Sure, not every meal was fly larvae. But as part of a complex picture of dietary preferences across the entire Neanderthal range, it’s important to consider the solutions that historic and recent humans have found, understanding how those solutions might apply to ancient cultures with similar nutritional needs and challenges. The work by Beasley, Lesnik, and Speth is part of that process.

A valuable offshoot of this kind of work is to inspire better approaches to the study of ancient animal remains and artifacts. How might processing of putrifying carcasses look different from fresh kills? What are the signs of insect activity on skeletal material that would be visible in archaeological bone? How did any of this really taste?

Answering those kinds of questions will be a task for the next generation of graduate students!

References

Beasley, M. M., Lesnik, J. J., & Speth, J. D. (2025). Neanderthals, hypercarnivores, and maggots: Insights from stable nitrogen isotopes. Science Advances, 11(30), eadt7466. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt7466

Ben-Dor, M., Gopher, A., Hershkovitz, I., & Barkai, R. (2011). Man the Fat Hunter: The Demise of Homo erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant. PLOS ONE, 6(12), e28689. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028689

Bocherens, H., Drucker, D. G., Billiou, D., Patou-Mathis, M., & Vandermeersch, B. (2005). Isotopic evidence for diet and subsistence pattern of the Saint-Césaire I Neanderthal: Review and use of a multi-source mixing model. Journal of Human Evolution, 49(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.03.003

Cachel, S. (1997). Dietary Shifts and the European Upper Palaeolithic Transition. Current Anthropology, 38(4), 579–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/204647

Crezzini, J., Modi, A., Cannariato, C., Caramelli, D., Ronchitelli, A., Boscato, P., Moroni, A., & Boschin, F. (2025). Neanderthal had a “crush” on fats. Macronutrient estimation in Middle Paleolithic (Late Mousterian) hunter-gatherers of southern Italy. Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fearc.2025.1558698

Hardy, B. L., & Moncel, M.-H. (2011). Neanderthal Use of Fish, Mammals, Birds, Starchy Plants and Wood 125-250,000 Years Ago. PLOS ONE, 6(8), e23768. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023768

Richards, M. P., & Trinkaus, E. (2009). Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(38), 16034–16039. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903821106

Schoeninger, M. J. (2014). Stable Isotope Analyses and the Evolution of Human Diets. Annual Review of Anthropology, 43(Volume 43, 2014), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-025935

Sistiaga, A., Mallol, C., Galván, B., & Summons, R. E. (2014). The Neanderthal Meal: A New Perspective Using Faecal Biomarkers. PLOS ONE, 9(6), e101045. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101045

Speth, John D. (2017). Putrid Meat and Fish in the Eurasian Middle and Upper Paleolithic: Are We Missing a Key Part of Neanderthal and Modern Human Diet? PaleoAnthropology, 2017, 44–72. https://doi.org/10.4207/PA.2017.ART105

Willoughby, Charles Clark. (1886). Indians of the Quinault Agency, Washington Territory. In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 267–82. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Putrefied meat with maggots is all very well if you ignore the bacteria that builds up in the decay. These bacteria cause mild to severe gut distress and food avoidances in primates as well as other animals with long guts adapted to diets of fruit, leaves, flowers, small live prey, and insects. Cooking makes scavenging a possible dietary source of protein which kills bacteria --leaving meat with and without maggots edible. Some of this is I discussed in a paper on scavenging and hunting and again in Diet and Food Preparation: Rethinking Early Hominid Behavior. SONIA RAGIR, 2000 Anthropology Today online). The high protein diet of Neanderthal may have only been possible with cooking--for which there is ample evidence among archaic homo and especially Neanderthals. The other high protein food made available to homo with food preparation such as grating, pounding, soaking & fermentation--and incidentally cooking are underground root stocks which are relatively indigestible without some preparation. The early dietary transition that included underground root stocks may have triggered an initial shift in body/brain development.

Food preparation would also include shifts in social organization--preparation includes a delay between foraging and eating--collecting bystanders to share the proceeds of the days root, nuts, berries and greens prepared by, perhaps mostly female, foragers--similar to the redistribution of the less reliable days hunt.