Bringing emotional cognition to deep time

In a new article, my coauthors and I draw upon cognitive science to draw out archaeological traces of ancient social lives

I am really pleased to see that my first article from 2026 has been released in the Journal of Archaeological Science. The article is a synthesis bringing together ideas from cognitive science and social behavior, and applying those to better understand the Pleistocene archaeological record. The article was led by Agustín Fuentes, together with Jennifer French, Marc Kissel, and Penny Spikins—all amazing collaborators whose work is helping to enable a clearer view of hominin behavior in the deep past.

The article is open access, and I hope everyone feels free to check it out. Here I’ll share my thoughts on some of the main ideas. What I’ll write isn’t necessarily the view of all my coauthors, but I think we’re in pretty broad agreement on these aspects of the work.

Emotional is rational

First, a quick setting of the scene. Natural selection is a calculus of survival and reproduction. Any individual’s time and energy are limited, and following one course of behavior may foreclose the possibility of others.

Behavior thus often involves trade-offs: Choosing to forage in more open habitats may improve food quality but increase the risk of predation. By delaying weaning, a mother may increase her infant’s chance of survival but may prolong the time until her next child can be born.

Humans today have faster spacing between births than any of our close living relatives. Chimpanzee and bonobo mothers tend to have an interval of five years between births, gorillas more than four, orangutans up to eight. For human mothers in natural-fertility societies the spacing between births is closer to three years.

This is possible because human mothers are supported in childrearing by other people, a practice known as allocare. Many anthropologists and behavioral ecologists have thought about allocare and what it means for the behavior of living people and our ancient relatives:

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has long been a thought leader in this area, first with her analysis of maternal support networks, and in her more recent book Father Time focusing on fathers and paternal care.

Kristen Hawkes has written about the role of grandmothers in allocare, with a focus on the trade-off for older mothers between investing in another—possibly risky—pregnancy and investing in the growing families of their existing daughters.

The late Frank Marlowe wrote about provisioning as an important aim of hunting in social groups of hunter-gatherers, as well as the role of men in protection.

For ants, bees, and other social insects, allocare is a matter of chemical signaling, including chemical controls on gene regulation that drive the development of workers. Humans are built different. We rely on the signaling and cognitive systems used by other primates for regulation of social relationships, and these center around emotion: anger, fear, surprise, sadness, joy, trust, disgust. A wider participation by other people in allocare required changes in emotional cognition: a greater ability to control or regulate emotions in some contexts, as well as changes to the interpretation or meanings of facial, vocal, and other signals of emotions.

Emotional changes overlap with some human-specific cognitive innovations that have been noted by Michael Tomasello, Richard Wrangham, and many others: Humans tolerate the proximity of other individuals, including strangers, vastly more than any other primates do, and humans can direct other individuals’ attention in ways that other primates rarely do. Such abilities rely upon emotional regulation, and they underlie most human collaboration and cultural learning.

This is all mainstream social psychology and behavioral ecology. What we observe in our new paper is that this cognitive background matters to the archaeological evidence left by Pleistocene hominins.

This idea bucks some long-held conceptions of “rationality” in Paleolithic archaeology. Actualistic research in archaeology—the kind that examines living hunter-gatherers as a model for past ways of life—has for decades focused upon measuring of the costs and yields of decisions made by foraging peoples: Measurements of caloric cost of locomotion, measurements of caloric returns of hunted animals and gathered plant foods, measurements of the distances and energy expenditure of raw material transport, measurements of the energetic and nutritional content of cooked food versus raw, of food supplementation for infants versus breast milk, of the energy yield of high-ranked and low-risk prey animals versus lower-ranked, higher-risk prey animals. Researchers may assume that ancient people strived to minimize costs and maximize returns in their decision-making.

Such analyses may be valuable and important but it is a mistake to limit consideration of “rational” behavior to those things that can be weighed or quantified with an oxygen mask on a treadmill. Human behavior engages social networks, and relies upon our mechanisms for social collaboration and cooperation. These involve emotional cognition. Consequential decisions entail the management of emotions, often of many people. People don’t avoid or minimize emotions in their behavior. They manage them.

Archaeological traces of emotional and social cognition

Signs of emotional management are not hard to see in the archaeological record once you start looking. The manufacture of stone tools to specific shapes, such as the iconic teardrop-shaped handaxe, would be impossible without the ability to share joint attention. Macaques and capuchin monkeys learn to crack nuts or shells by watching from a distance, and Lomekwian hammering might conceivably require little more. But young chimpanzees learn to crack nuts and making many other kinds of tools by close observation of their mothers, and it’s likely that the selection of appropriate raw material and rotation of cores by Oldowan toolmakers would have required a higher tolerance of close observation by older children or adults.

In our article, we point to healthcare as strong evidence of emotional cognition. Humans often help the sick and injured, sometimes for prolonged periods of time and at great cost. Healthcare in this sense has been present across societies worldwide, although there are cultural differences that affect who may be eligible for such help, and how it is delivered. In these aspects healthcare is like allocare of infants and children—it matters who they are, how they are related to others in the group, and what forms of care may be provided.

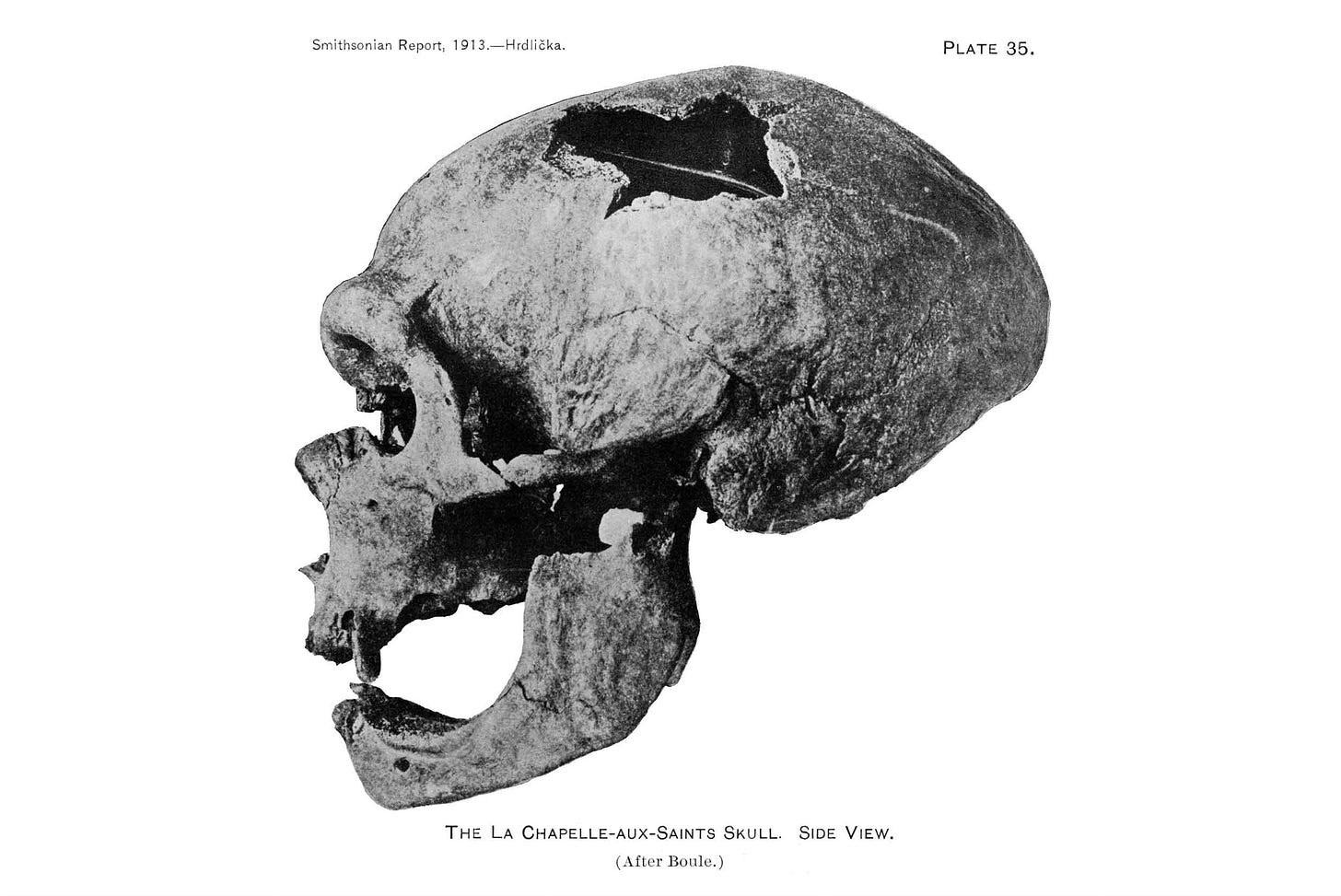

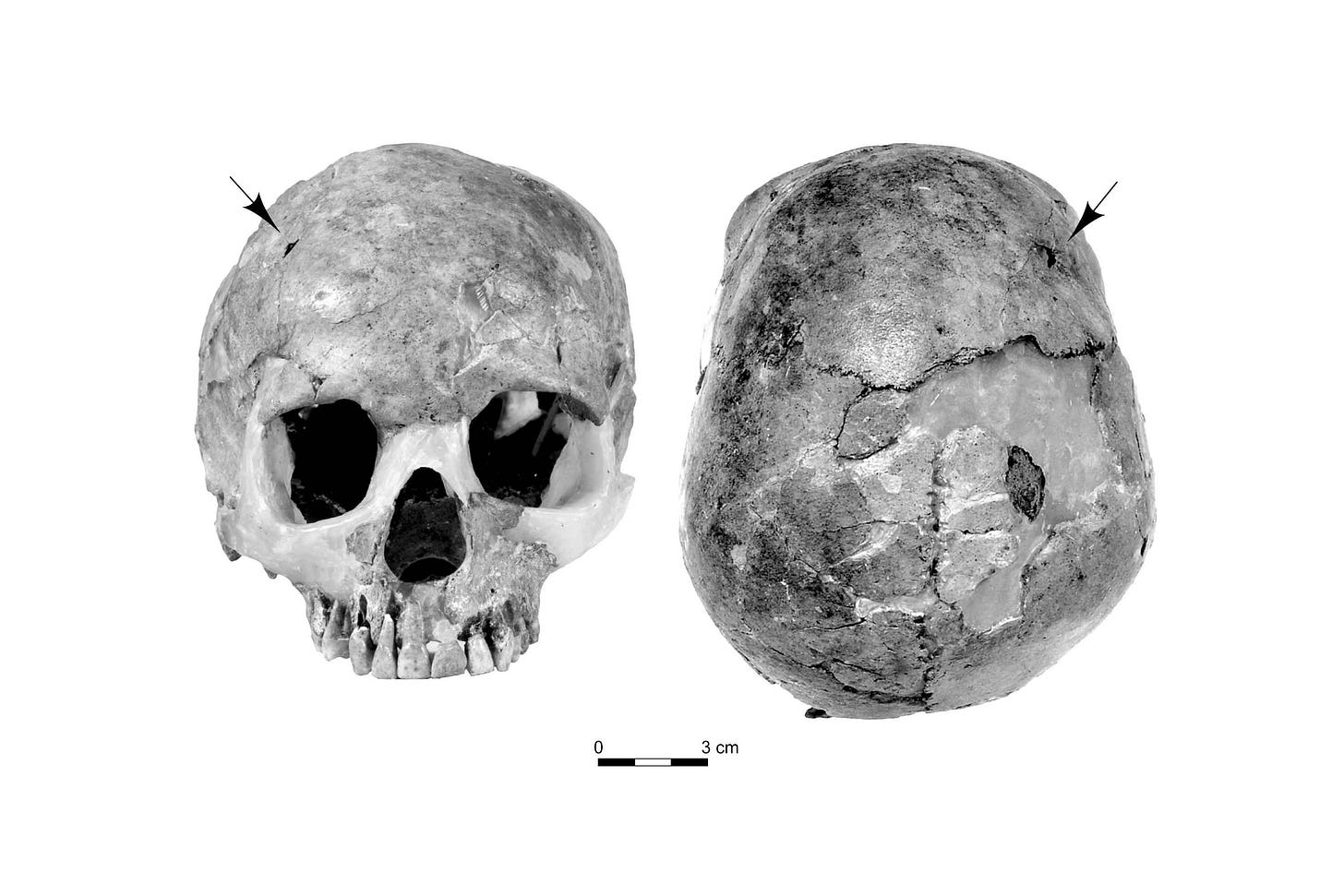

There is growing evidence of healthcare in the archaeological and skeletal record of hominins. In our article we point to some of the famous cases, like the KNM-ER 1808 individual, who lived around 1.6 million years ago and survived for some time with debilitating and painful periosteal reaction and cortical bone thickening. In the Middle Pleistocene, the case of craniosynostosis of the Cranium 14 individual from Sima de los Huesos is notable; in the Late Pleistocene record, Neanderthals with evidence of extensive osteoarthritis, losses of limbs, and near-complete loss of teeth are also very well known.

The point of these examples is not to suggest something extraordinary or unique about the specific individuals involved. After all, sick and injured individuals sometimes survive or overcome disabilities in societies of nonhuman primates. Instead, what is interesting about the pattern in Pleistocene hominins is how they reveal the umbrella of caregiving extending beyond allocare of infants and young children across a broader segment of society, at least in some contexts.

Why do we care for the sick? I don’t know how many times I’ve read previous writers suggesting that ancient people were sneakily rational: Sure, they cared for aging individuals, but their real motive was that the cultural knowledge of older people had great value. But I think it is short-sighted to see Pleistocene healthcare as a quid pro quo. Empathy is a building block of social cognition in hominins. I doubt that it’s possible to build a system of social collaboration without that empathy sometimes manifesting as care.

Likewise, mortuary behavior is universal across human societies today. Many—although far from all—kinds of mortuary behavior leave traces that can be archaeologically visible. One form of mortuary behavior is burial, and the burials of many Neanderthals in Late Pleistocene contexts have gotten a great deal of attention, as has the evidence of burial that I’ve helped publish on the Middle Pleistocene species Homo naledi.

There are many other ways that mortuary behavior may be manifested in archaeological sites. From the evidence for curation and handling of the skulls from Herto, Ethiopia, to the cutmarks on the face of the Bodo 1 skull, also from Ethiopia, to the occurrences of cannibalism at several Neanderthal sites, all these are doorways into the practices surrounding death in their respective hominin groups.

As Emma Pomeroy and others have reviewed, mortuary behaviors are manifested in many other living species of mammals. From our close relatives like chimpanzees and gorillas, to more distant social mammals in many orders including orcas, elephants, and horses, individuals alter their behavior when encountering dead bodies of their own species. They may exhibit profound grief or sadness, they may show fear, and in some heartbreaking cases they continue to manifest care—intervening to try to revive or sustain a juvenile or adult group member—days or weeks after death has occurred.

Humans and our close hominin relatives have often elaborated these natural reactions to death into shared rituals that integrate emotion and memory within our social groups. Culture gives us a shared setting for grief, and emotional cognition enables us to empathize more widely. Such funerary rituals are a part of the collaborative construction of new futures, providing some structure in the absence of the valued deceased.

No behavioral modernity

In our article we don’t get much into pigments, ornaments, cave art, or other signs of “symbolic” culture. But these, too, reflect the growing importance of emotional regulation and social collaboration in our evolutionary history.

Steven Kuhn and Mary Stiner have emphasized that ornaments have a primarily social function. Wearing a distinctive bauble, having a visible tattoo, or marking one’s garments or skin pigment all have the effect of making strangers aware of the wearer’s status and rank within society. Archaeologists are increasingly focusing upon the demographic aspect of these kinds of behavior: As the population grows there are not only more people, there are more social groups, more need for communication among strangers, and more encounters between people who may not share a common language.

There is also a greater chance in a larger population that a new skill or idea may be transmitted forward to other people. The half-life of information depends on how many people there are. It also depends on how willing people are to share space with each other. Emotional cognition and social collaboration are at the core of these abilities. Markers of social identity, rank, and status are some of the best indicators of this system in the archaeological record.

Back in the 1980s, some archaeologists imagined that recent humans were products of a “cognitive revolution” that set them apart from earlier people like Neanderthals. This “great leap forward” was marked by blades, ornaments, and above all, cave art. It was inevitable that some researchers hypothesized that recent people had emerged as a new, anatomically modern set of populations that carried advanced cultural and cognitive abilities.

There was a problem with this idea even at the time. There were archaeological sites like Skhūl, Israel, where people with so-called “modern” anatomy seemed to have had indistinguishable cultures from those at other sites with burials of Neanderthals. Some researchers suggested that anatomical modernity was not the important dimension. What mattered was behavioral modernity: the real revolution was in the brain, not the body.

By 2000, Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks could detail the gradual appearance in Africa of many innovations that had once been assumed to have emerged suddenly in Europe. There was no “human revolution”, they wrote. There was a gradual evolution of material culture piecemeal across Africa through much of the later Middle Pleistocene. Even so, many archaeologists took as their working assumption that the African archaeological record documents the gradual transition to behavioral modernity, which includes symbolic culture shared by all living people.

We think that the idea of behavioral modernity has obscured the deeper causes of evolution of behavior in humans and other hominins. Again and again, archaeologists have fallen back on the notion of a “transition”—whether fast or slow—with the implicit idea that the transition was singular and progressive.

Biologists study evolutionary change by understanding phylogeny. The phylogeny of Pleistocene Homo involves the divergence of some groups over many hundreds of thousands of years, and networks of contacts and interbreeding connected many of those groups.

All of them were social species. As we write, individuals did not “live outside social groups, at least not for long or typically”. As children they met their ecologies through the interface of other individuals; they rarely survived without others. Their niche was learned socially and propagated by construction of rules, conventions, and habits.

Even if archaeologists could recognize “symbolic” culture from artifacts—which is far from clear—the fact is that symbolism is not the primary basis of collaboration and cooperation in living humans. I would go a bit further than we do in the article. My personal view is that much that has been called “symbolic” in the archaeological record should instead be understood to reflect shared emotional regulation. It is fascinating that some ancient people and other hominins ventured far into caves to make marks on their walls. But the important bit is not the marks—which are, after all, found fairly widely across the Pleistocene world. What’s actually fascinating is the shared journey.

We are not our ancestors. Humans today are often innovative, creative, and strategic in ways that we do not see in deep time. These aspects of human behavior do draw upon emotional cognition but they require integration with other kinds of cognition also. Besides this, we are aided by communication systems that never existed in any Pleistocene society, extending the reach of our attention and forethought.

How can we get at the evolution of these abilities, which we continue to invent? My thought is that what matters today is not well correlated with the kinds of archaeological traces that have been grouped as “behavioral modernity”. The data tell us that those very traces are shared by many Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other ancient groups. However, better understanding the basis of social collaboration among Pleistocene groups is certainly a valuable start.

References

Mayer, D. E. B.-Y., Groman-Yaroslavski, I., Bar-Yosef, O., Hershkovitz, I., Kampen-Hasday, A., Vandermeersch, B., Zaidner, Y., & Weinstein-Evron, M. (2020). On holes and strings: Earliest displays of human adornment in the Middle Palaeolithic. PLOS ONE, 15(7), e0234924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234924

Fuentes, A., French, J. C., Hawks, J., Kissel, M., & Spikins, P. (2026). Social and emotional cognition in Pleistocene hominin evolution: The role of biocultural processes. Journal of Archaeological Science, 185, 106441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106441

Hawkes, K. (2003). Grandmothers and the evolution of human longevity. American Journal of Human Biology, 15(3), 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.10156

Hrdy, S. B. (2005). Comes the Child before Man: How Cooperative Breeding and Prolonged Postweaning Dependence Shaped Human Potential. In Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods. Routledge.

Hrdy, S. B. (2026). Father Time: How Nurturing Is Natural for Men. Princeton University Press.

Hrdy, S. B., & Burkart, J. M. (2020). The emergence of emotionally modern humans: Implications for language and learning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1803), 20190499. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0499

Kuhn, S. L., & Stiner, M. C. (2007). Paleolithic Ornaments: Implications for Cognition, Demography and Identity. Diogenes, 54(2), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107076870

Marlowe, F. (1999). Showoffs or Providers? The Parenting Effort of Hadza Men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 20(6), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00021-5

Mcbrearty, S., & Brooks, A. S. (2000). The revolution that wasn’t: A new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. Journal of Human Evolution, 39(5), 453–563. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2000.0435

Pomeroy, E., Hunt, C. O., Reynolds, T., Abdulmutalb, D., Asouti, E., Bennett, P., Bosch, M., Burke, A., Farr, L., Foley, R., French, C., Frumkin, A., Goldberg, P., Hill, E., Kabukcu, C., Lahr, M. M., Lane, R., Marean, C., Maureille, B., … Barker, G. (2020). Issues of theory and method in the analysis of Paleolithic mortuary behavior: A view from Shanidar Cave. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 29(5), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21854