Complex fiber and wood technologies of the first Great Basin peoples

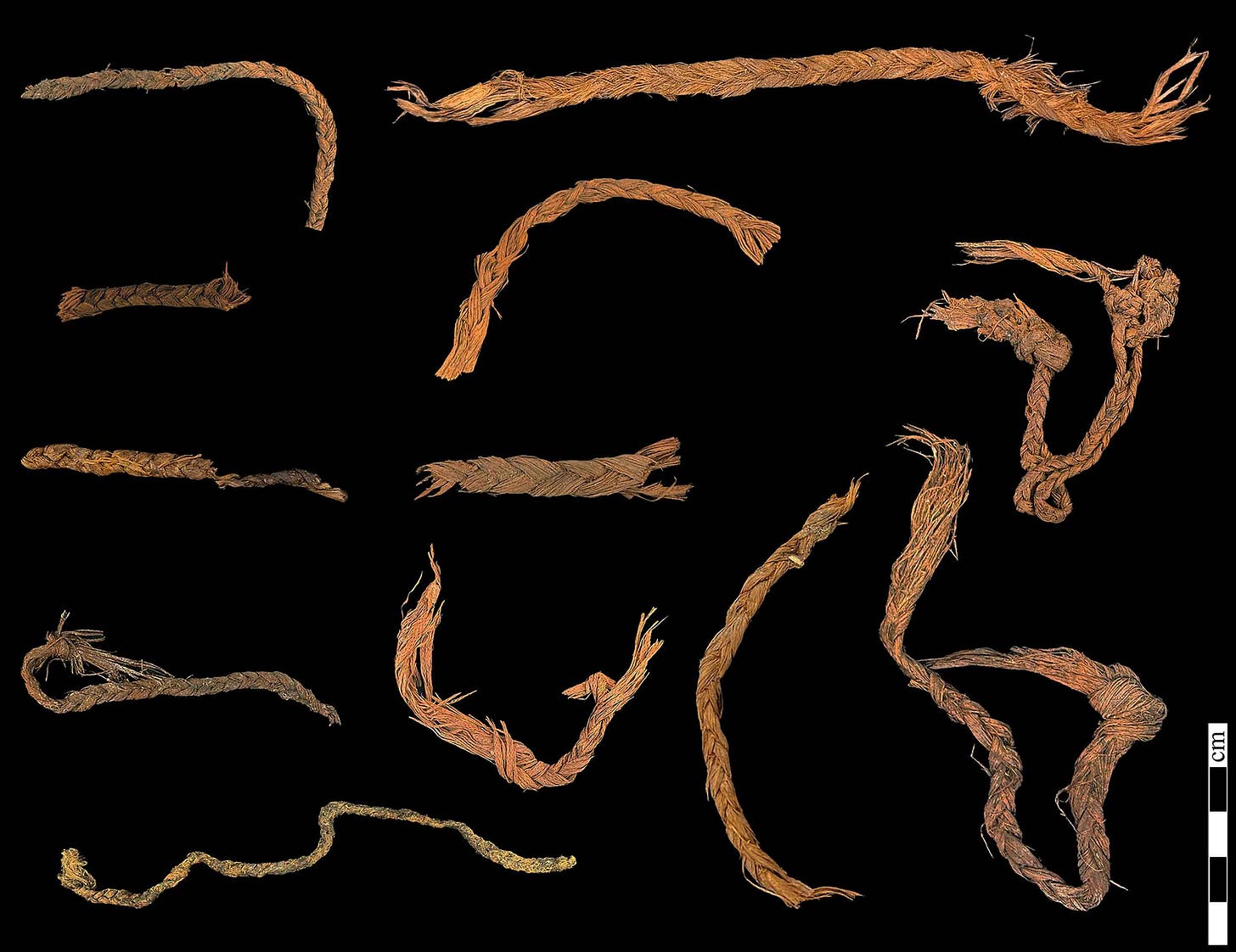

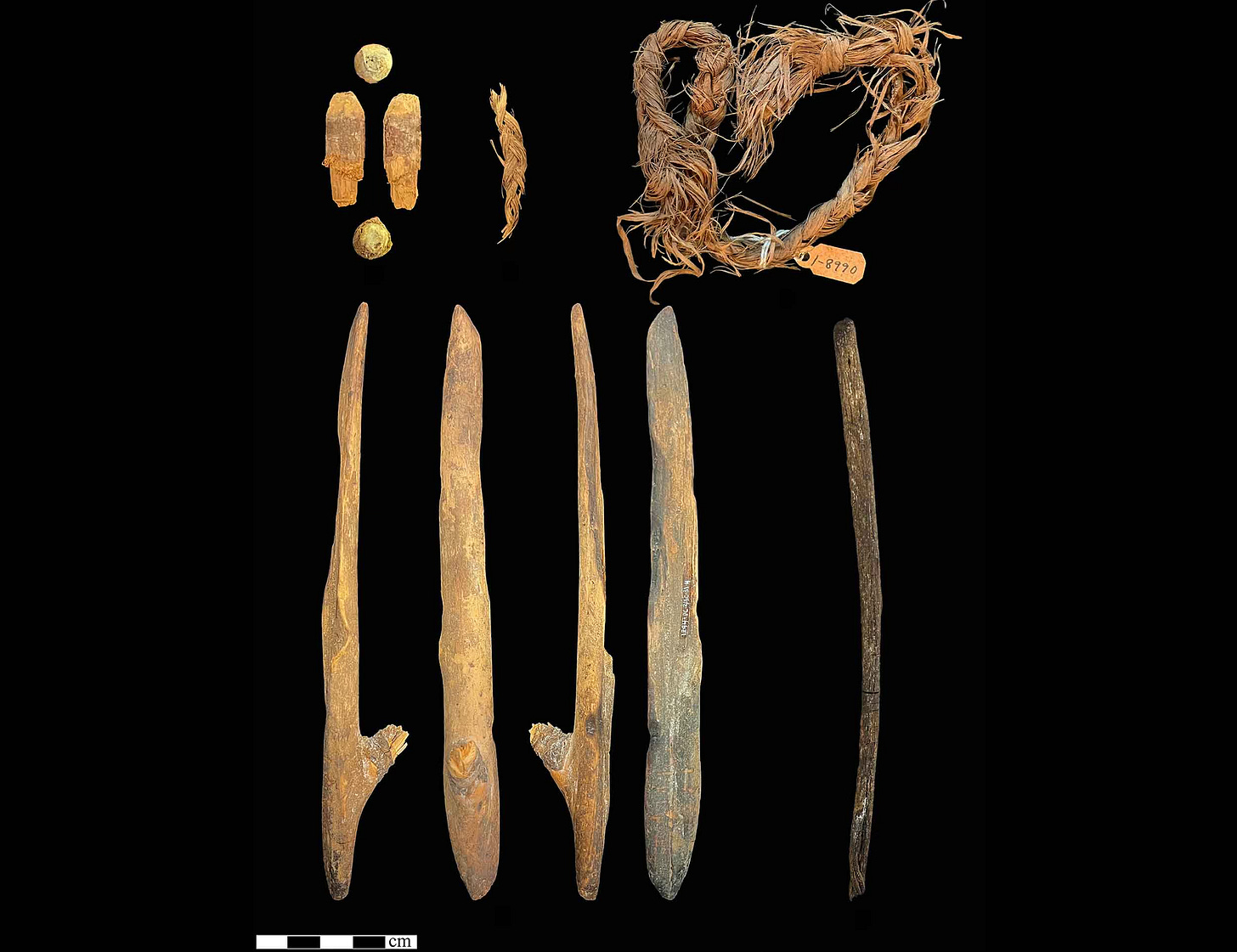

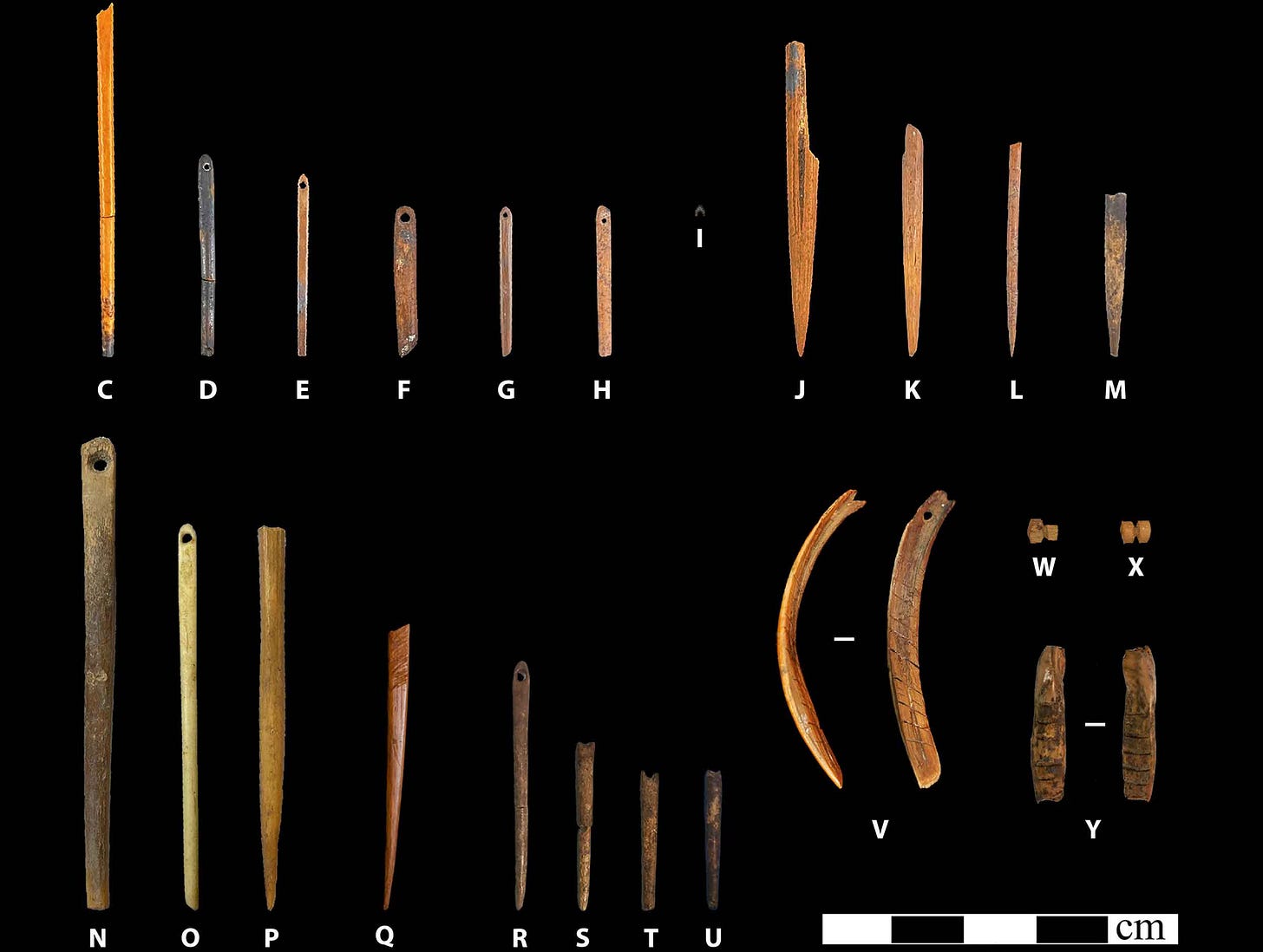

From Cougar Mountain Cave and Paisley Caves, Oregon, come remarkably preserved examples of perishable materials.

Ancient peoples crafted technologies from wood, fiber, bark, leather, sinew, feathers, and countless other organic materials. With these they made all manner of implements, clothing, watercraft, and structures. Some such items were simple, made from only a single piece like a digging stick. But most were complicated, made from many pieces, each piece shaped in ways necessary to the overall function.

Nearly all these things have passed into dust.

Still, a few archaeological sites provide exceptional records of ancient organic technologies. They come only from particular times and places: Desert caves, anoxic peat bogs, or fine silty sediments that preserve impressions of objects long decayed.

I’m fascinated by a new article that reports on some of the preserved organic technologies from caves of the Great Basin of North America. The first peoples to leave traces in these caves lived more than 13,000 years ago. The article, by Richard Rosencrance and collaborators, discusses the ways of life that were supported by tightly sewn clothing, cordage, carved wooden traps, and other perishable technologies. Most of the artifacts described in their work come from Paisley Caves and Cougar Mountain Cave, both in eastern Oregon.

Both Paisley Caves and Cougar Mountain Cave were first investigated by archaeologists more than 60 years ago—Paisley Caves by Luther Crossman in the 1930s, Cougar Mountain Cave by John Cowles in 1958 and later by Thomas Layton in 1966. Recording of the positions and context of material in these early excavations was not as precise as might be wished, and some aspects that might be highly interesting today were not systematically collected and ended up in backfill.

At Cougar Mountain Cave, Rosencrance and coworkers relate Cowles’s reporting that many coprolites were in the deposits, and these were not collected. That’s a pity because at Paisley Caves, more recent excavation led by Dennis Jenkins brought to light many human coprolites, which have provided an abundance of biological information about the ancient people who left them.

The jewel of the earlier excavations were the recognition of artifacts of fiber, leather, bark, and wood. The collection by Cowles and Layton from Cougar Mountain Cave includes a wide range of exceptional material, now housed at the Nevada State Museum. The new work by Rosencrance and coworkers includes a lot of new analysis of this collection, with radiocarbon dating on many of the artifacts.

Both sites cover a range of dates but much of the most interesting material comes from the period of time known as the Younger Dryas, roughly 12,900 to 11,600 years ago. In a world that was generally warming from the Last Glacial Maximum 19,000 years ago, the Younger Dryas represents a resurgence of relatively cold conditions.

Rosencrance and coworkers focus on the pattern of technical complexity represented by these objects. Many involve the application of multiple techniques or tools in their production.

One kind of example is tailored clothing. For example, a fragment of elk hide from Cougar Mountain Cave of Younger Dryas age has a cord sewn into its edge—the oldest example of sewn hide in the world. This is too small a fragment to know whether it was part of a garment or moccasin. But the utility of needles and sewing in producing fitted garments and footwear is widely recognized. Tailored clothing was valuable in cold environments as a means of reducing energy expenditure and avoiding frostbite, and the article presents evidence of bone and wood needles from many sites in addition to the two sites with most of the fiber and hide preservation.

Another example is weaving rushes or plant fibers into mats or baskets. Fragments of woven plant material are evidenced in both the Paisley Caves and Cougar Mountain Cave collections.

A different type of complexity is the production of special parts that must function together within a compound implement or machine. Some of the wooden pieces in the collections are interpreted as parts of deadfall traps, in which a large stone is supported by an intricate set of sticks that trigger the fall of the rock when disturbed by a small animal.

The article discusses a concept rooted in the ecology of northern hunter-gatherers that has a broad utility when thinking about such complex organic repertoire: the idea of “serial specialists”. This term was used by Lewis Binford as a way to think about the ecological flexibility and shifting foraging strategies that are needed in places where resources may have specific seasonal patterns.

“The cold-environment foragers are what I tend to think of as serial specialists: they execute residential mobility so as to position the group with respect to particular food species that are temporally phased in their availability through a seasonal cycle.”—Lewis Binford

The idea is that people move during the year—residential mobility—and pursue specialized foraging or extraction strategies for each of the resources they rely upon. One key requirement is being in the right place at the right time. That means learning the timing of the resource and the affordances of the landscape around it. Another key requirement is knowing how to make the specialized implements or follow the specific procedures that enable exploitation of the resource.

Binford emphasized that this was different from a generalist strategy; it’s a strategy of becoming specialists in multiple distinct survival activities.

The ethnographic record of Great Basin groups like the Northern Paiute provides a lot of evidence for this kind of sequential application of different specialized foraging strategies across an annual cycle. These groups moved to exploit specific resources with seasonal abundance, such as the hatching of brine fly larvae in Mono Lake, the harvest of piñon pine nuts, and the communal driving and capture of jackrabbits.

It’s very hard for any single site to provide evidence about residential mobility. Evidence of different activities at a single site doesn’t quite do this: A forager who can craft a well-balanced spear point for bison and a deadfall trap for a rabbit is mastering two very different technologies, yet may employ them in the same place and time. True, the archaeological record sometimes comes through in surprising ways: at some sites archaeologists can establish that human activity was seasonal, often through the preservation of botanical remains or animals that were killed at a single time of year. Still, piecing together an entire cycle would take an impressive correlation from many archaeological sites across a region, all representing the same range of time.

Sites in the northern Great Basin that share Younger Dryas-age deposits might provide such correlations. They fall within a limited timespan and share a Western Stemmed stone tradition. At Paisley Caves, the coprolites have produced abundant biological evidence including dietary remains and mitochondrial DNA.

These sites have received a lot of attention as part of the long debate over whether they provide evidence of human activity prior to the widespread Clovis tradition. The Clovis phenomenon is named for the distinctive fluted spear tips found at a mammoth kill site at Blackwater Draw, near Clovis, New Mexico, and similar points and associated finds stretch from Canada to Central America, with a strong concentration in the southeastern United States. Sites with Clovis points are concentrated in a narrow band of time just before the Younger Dryas, from just over 13,000 to around 12,750 years BP.

Some of the human coprolites from Paisley Caves are indeed older than Clovis, ranging as much as 14,800 years BP, and are authenticated with mitochondrial DNA and fecal sterol chemistry. Only one of the fiber items described by Rosencrance and coworkers comes from sediments predating the Younger Dryas; the rest are contemporary with Clovis or more recent.

The initial habitation of this part of North America is indeed an important topic. I’m just as interested in the connection between Paisley Caves, Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, and other sites that predate the Clovis phenomenon as anyone.

Even so, the work from these sites has me much more often thinking beyond the question of who was earliest.

What is most valuable in understanding the lives of the ancient people—including their adaptability upon their arrival in new circumstances—is the richness of the record of behavior. In that regard, these sites from the northern Great Basin have few parallels. I can’t wait to see more examination of the biological evidence from these sites, their interrelationships across sites, and their connection to the surrounding environment.

Notes: All dates in this post are in calibrated years BP, and I’ve generally limited to round numbers. In the debate over the timing of sites relative to Clovis more significant digits are sometimes needed, and changing calibration scales sometimes argue for reporting radiocarbon years rather than calibrated years.

References

Binford, L. R. (1980). Willow Smoke and Dogs’ Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation. American Antiquity, 45(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/279653

Jenkins, D. L., Davis, L. G., Stafford, T. W., Campos, P. F., Hockett, B., Jones, G. T., Cummings, L. S., Yost, C., Connolly, T. J., Yohe, R. M., Gibbons, S. C., Raghavan, M., Rasmussen, M., Paijmans, J. L. A., Hofreiter, M., Kemp, B. M., Barta, J. L., Monroe, C., Gilbert, M. T. P., & Willerslev, E. (2012). Clovis Age Western Stemmed Projectile Points and Human Coprolites at the Paisley Caves. Science, 337(6091), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1218443

Rosencrance, R. L., Smith, G. M., Jenkins, D. L., Connolly, T. J., & Layton, T. N. (2019). Reinvestigating Cougar Mountain Cave: New Perspectives on Stratigraphy, Chronology, and a Younger Dryas Occupation in the Northern Great Basin. American Antiquity, 84(3), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2019.22

Rosencrance, R. L., Smith, G. M., McDonough, K. N., Jazwa, C. S., Antonosyan, M., Kallenbach, E. A., Connolly, T. J., Culleton, B. J., Puseman, K., McGuinness, M., Jenkins, D. L., Stueber, D. O., Endzweig, P. E., & Roberts, P. (2026). Complex perishable technologies from the North American Great Basin reveal specialized Late Pleistocene adaptations. Science Advances, 12(6), eaec2916. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aec2916

Shillito, L.-M., Whelton, H. L., Blong, J. C., Jenkins, D. L., Connolly, T. J., & Bull, I. D. (2020). Pre-Clovis occupation of the Americas identified by human fecal biomarkers in coprolites from Paisley Caves, Oregon. Science Advances, 6(29), eaba6404. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba6404