Fossils from the Grotte à Hominidés, Morocco, and crossroads of human evolution

Jaws, teeth, and a hyena-chewed femur may be close to the common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern people.

Neanderthals, Denisovans, and African ancestors of modern people are a deep trident of populations whose tendrils spanned Africa, Europe, and Asia. The Neanderthals and Denisovans began to differentiate around 600,000 years ago from a small ancestral group. That group, the “Neandersovans”, began an estimated 825,000 to 700,000 years ago as one small thread from a tangle of populations. Some larger strands from this tangle lead to later African populations, including ancestors of modern people.

This much we know from genomes. Maybe paleoanthropologists have already found fossils of those ancestral populations. But which fossils could they be?

In a new study, Jean-Jacques Hublin and collaborators highlight the fossil hominins from Grotte à Hominidés, Morocco. Their new work places the fossils’ geological age in the time shortly before 773,000 years ago. The Grotte à Hominidés fossil teeth and jaws share some patterns of shape with humans and Neanderthals that are not seen in Homo erectus. Hublin and coworkers describe the fossils as a “basal lineage” to our species, Homo sapiens.

That place in the hominin tree is the big tangle.

Could the Grotte à Hominidés fossils be a thread that led to modern people or Neandersovans? You can be sure I have an opinion.

Context of the fossils

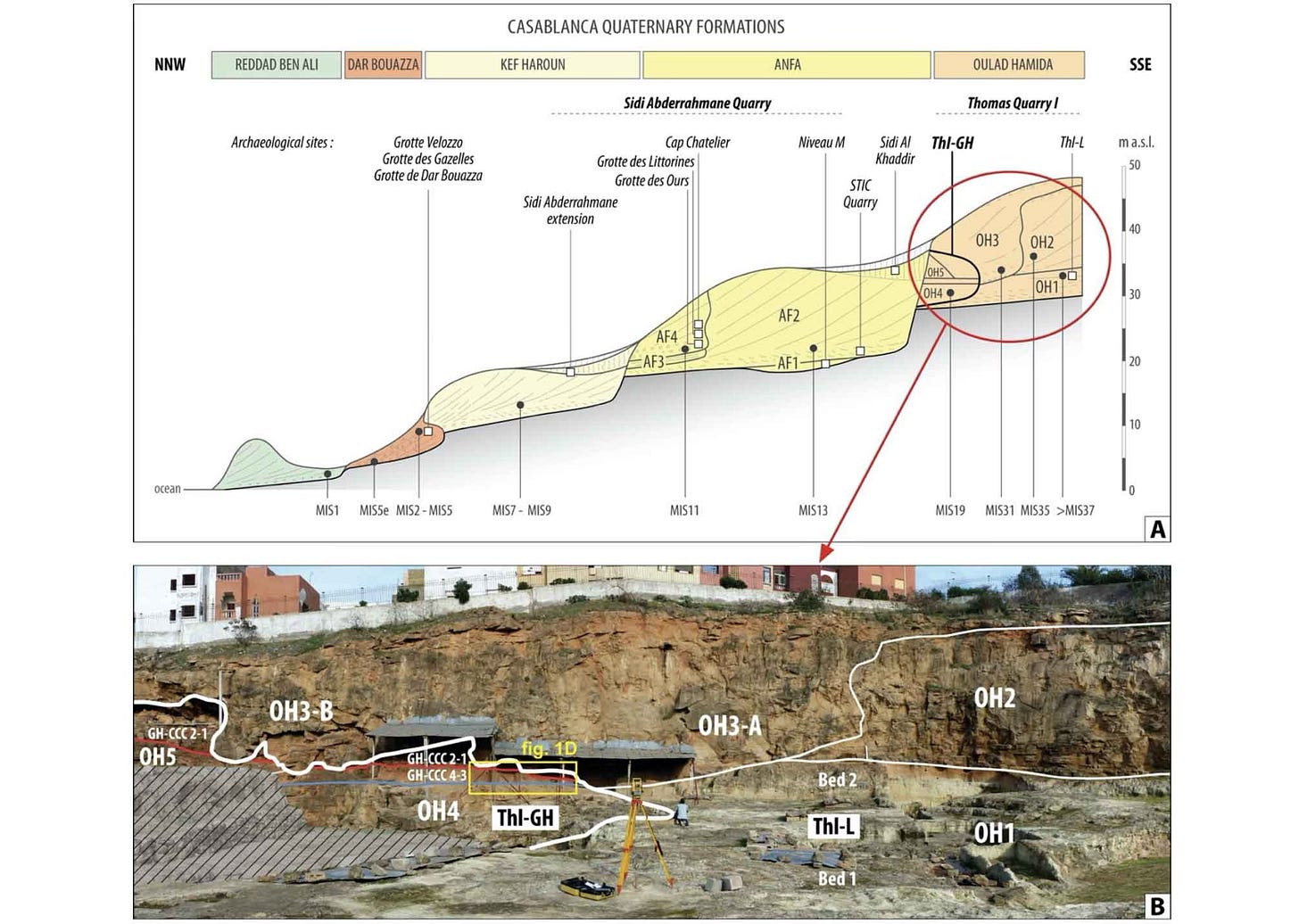

The Thomas Quarry I (ThI) site in general and the Grotte à Hominidés (ThI-GH) are not new discoveries. This and other sediment deposits are exposed on the wall of a large quarry, which archaeologists have investigated for more than 60 years.

The quarry is within the outskirts of the city of Casablanca, near the present-day Atlantic coastline. The sediments are partially cemented together by calcite, some deposited by wave or water action and some carried by wind. Today the site is around 28 meters above sea level, but sometime in the later Early Pleistocene, when the sea was at a higher level than today, wave action carved a cave into the existing sediment deposits and cliff face. This cavity is the Grotte à Hominidés.

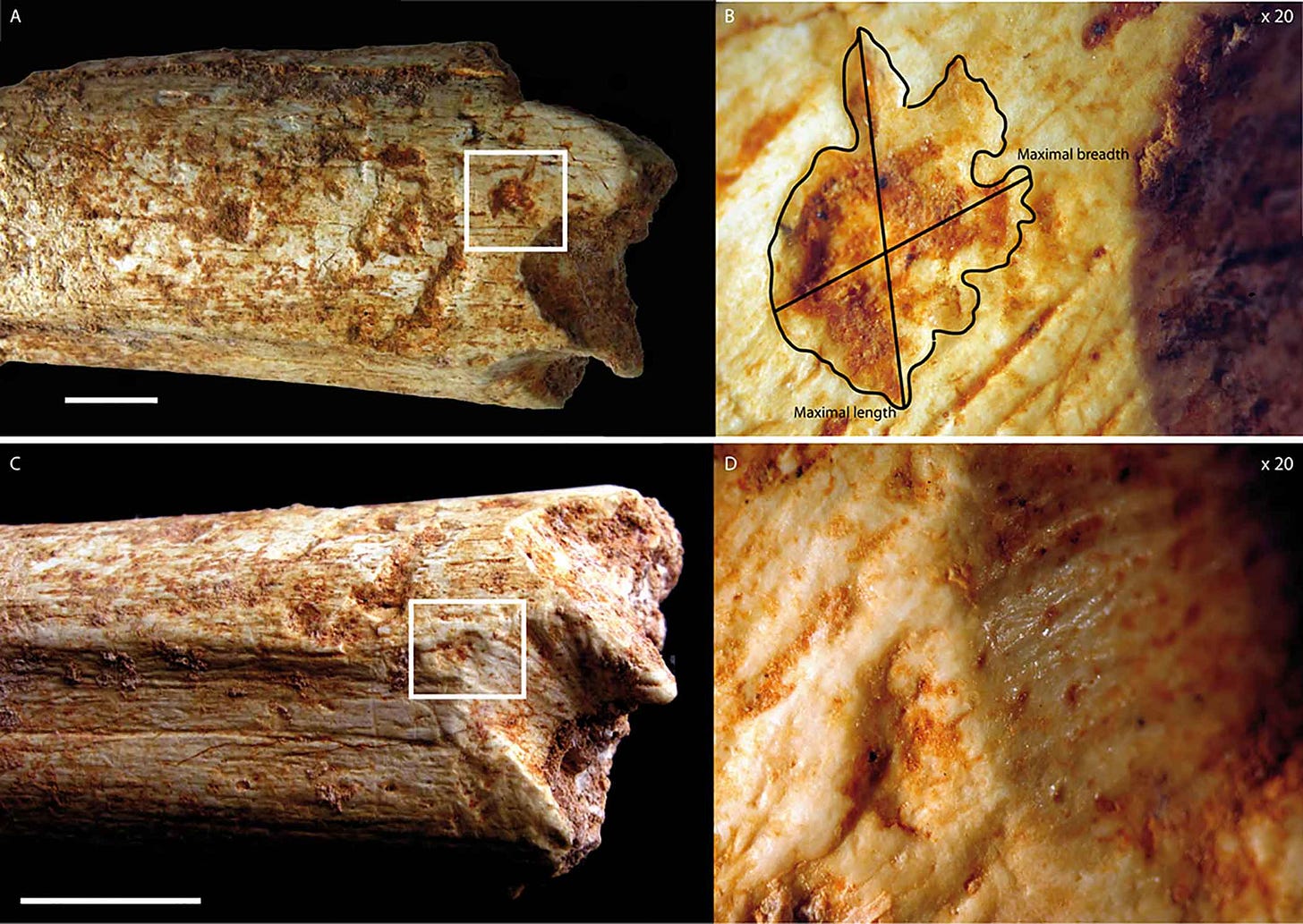

Half a hominin mandible was discovered in 1969, which would draw archaeologists’ attention to this part of the quarry, where they found the cave. By 2011, teams had uncovered many stone tools and ancient animal remains from the ThI-GH sediments. Under the leadership of Jean-Paul Raynal they reported some isolated hominin teeth in 2012, and in 2016, they described a human femur shaft fragment that had been chewed by a large carnivore, likely a hyena.

Other hominin remains recovered in the excavations from before 2011 are reported in the new study by Hublin and coworkers. They include a complete mandible excavated in 2008, ThI-GH-10717, and a series of vertebrae found near it that may represent the same individual. They also include a small section of juvenile mandible and teeth, ThI-GH-10978.

The stone tools within the GH deposit include cores made from quartzite or silicite beach cobbles, flaked bifacially. The flaking techniques and a few handaxes mark the assemblage as Acheulean. There’s little evidence that anyone made stone tools within the cave.

The large assemblage of animal bones appears mostly to have been accumulated by carnivores, with jackal-sized tooth marks especially common. None have cutmarks from hominins.

How did the hominins arrive? There is no occupation floor or significant activity that could be attributed to one group’s lifetimes. At least one individual was ravaged by carnivores, like most of the nonhuman remains. The occasional tool may have been discarded in the cave when people sheltered near the entrance of the cave or used it for shade when foraging closer to the shoreline.

Geological age

Hublin and coworkers report that the fossils come from individuals who lived close to the major Matuyama-Brunhes paleomagnetic reversal, around 773,000 years ago. Their conclusion is based on 119 new samples of magnetic orientation across the sediment layers before, during, and after the Grotte à Hominidés infilling.

An age as early as 773,000 years ago seems to contradict a lot of other work that the geochronologists have done in the site. Electron spin resonance (ESR) combined with uranium-series (US) dating led to estimates for animal teeth from the hominin-containing layers as old as 700,000 and as recent as 400,000 years ago, and ESR-US reported on one of the hominin teeth gave an age between 595,000 and 426,000 years. Those approaches guided earlier interpretation of the site, including the 2016 study that reported the hyena-chewed GH femur, which has “500,000-year-old” in the title. The ESR-US timeline is seemingly reinforced by optically-stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of sediment samples, which suggested they were between 450,000 and 350,000 years old.

Hublin and colleagues resolve the site’s chronological discrepancies by leaning heavily on paleomagnetism. Because the hominin layers show reversed magnetic polarity, they conclude the site must be older than 773,000 years. They treat the ESR-US dates as minimum ages—citing issues with uranium uptake—and discard the OSL ages altogether.

While this narrows the timeline, the fossils still likely represent populations scattered across thousands of years. Without clear signs of a specific ‘moment’ in time, like a brief cultural occupation, precision is less vital to me than accuracy. I prefer an accurate broad range over a precise range that is potentially incorrect.

Where do these fossils fit?

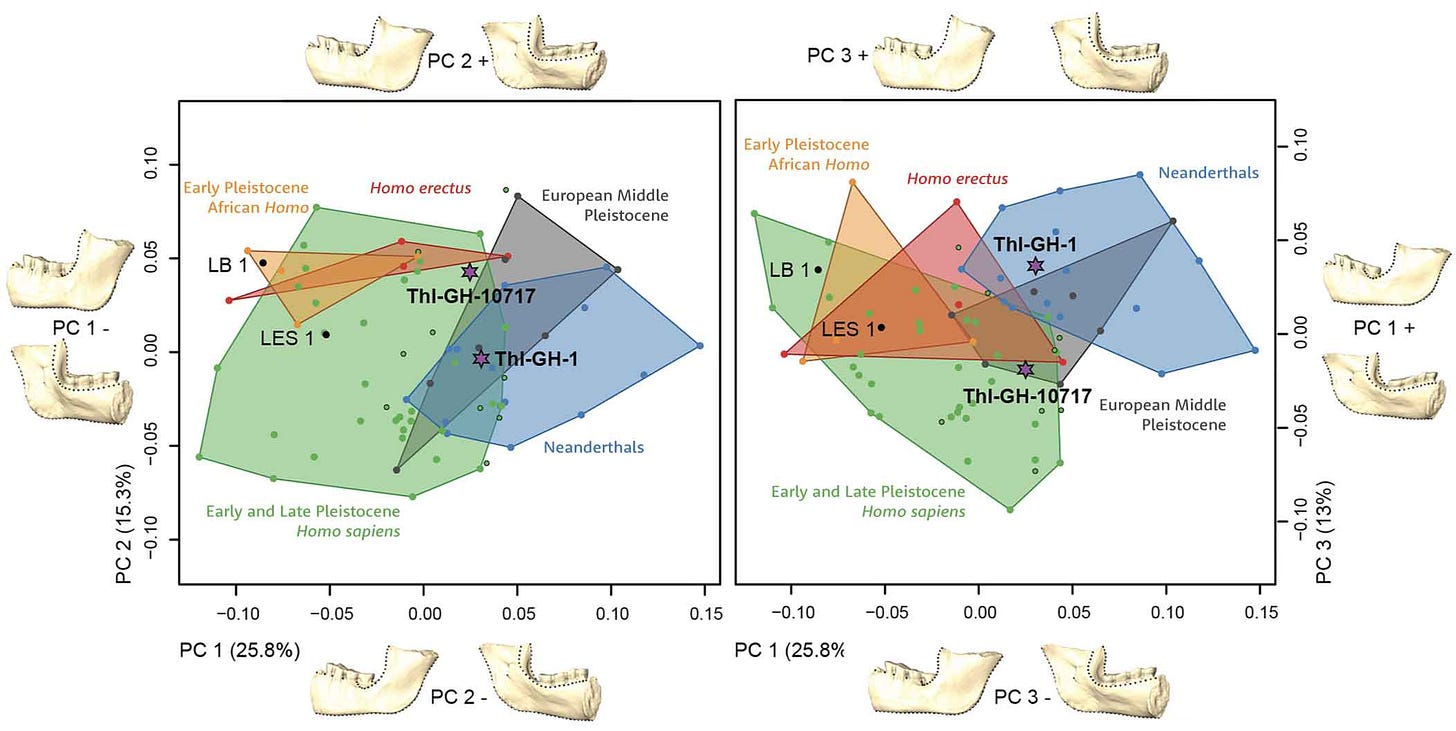

The new study persuades me that the ThI-GH fossils don’t fit easily into the variation of Homo erectus. Nor do they share most of the traits of recent humans or Neanderthals. If I were trying to imagine a population connecting these other groups, I might imagine something like these.

The teeth carry the most information, just because there are more teeth than other parts, and they show an anatomical mosaic. Each graph with one of the ThI-GH teeth is a different picture. Some show ThI-GH teeth are within the range of recent human form, some are like Homo erectus, in a few cases like Neanderthals, and often off by themselves.

Hublin and coworkers present principal components plots to compare the shapes of the two adult ThI-GH mandibles with other groups. In this particular kind of shape comparison, modern humans and Neanderthals are fairly consistently different—I suspect because their samples are the largest—and the Th1-GH mandibles are near the small area of overlap between these groups. The European Middle Pleistocene mandibles, including early Neanderthals from Sima de los Huesos—also are within that area of shape overlap.

Beyond the multivariate methods, the complete ThI-GH-10717 mandible is a very small one. It’s smaller in size than any H. erectus mandible. Its third molars are particularly small compared both to H. erectus and H. antecessor. Its mandibular corpus height and breadth are smaller than any H. erectus or H. antecessor mandibles. Its small size does fall within the range of modern humans and Neanderthals.

The vertebrae are more erectus-like than modern or Neanderthal, but the aspects they share with Homo erectus are all ancestral traits, not derived similarities that would be evidence of a close relationship.

The hypothesis that connects these results is that the ThI-GH fossils come from a group close to the node that connects all these groups on the tree.

It’s never easy to sort out the details of fossil relationships close to ancestral nodes. Without long branches separating them, such groups did not develop much derived anatomical variation of their own. Instead, genetic drift and selection tend to reapportion variation from ancestral populations, leading to a mosaic.

Bottom line

In my way of thinking, these fossils are Homo sapiens. They fall somewhere within that tangle of groups that ultimately gave rise to Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern people.

Until now, the hominin fossils that are closest to the same place in the tree of relationships are the fossils from Gran Dolina, Spain, attributed to Homo antecessor. These hominins lived sometime between 949,000 and 773,000 years ago, overlapping with the time Hublin and coworkers propose for the ThI-GH fossils. Both the anatomy and the protein data from Homo antecessor fossils show them to be closer to the Neanderthal-Denisovan-modern branch than to Homo erectus.

The obvious question is whether these fossils from Grotte à Hominidés and Homo antecessor are simply the same thing. I thought the study would answer this question. It really doesn’t. The ThI-GH dental sample differs only in a handful of traits from the Gran Dolina sample. I don’t think the study rejects the hypothesis that these belong to similar or closely related populations.

More likely than not, both the Grotte à Hominidés fossils and Gran Dolina fossils shared ancestors within the few hundreds of thousands of years before they lived. They may well both be part of the tangle.

We’re now a decade or more into a simmering scientific debate about whether the Neanderthal-Denisovan-modern (N-D-M) ancestral population lived in Africa, or whether instead those ancestors lived in Eurasia. It may seem intuitive that Africa is the ancestral location, since African groups already had begun to differentiate at the time the Neandersovan founders lived. What has prompted the debate is Homo antecessor—the closest known outgroup to the N-D-M branch, but ensconced at the extreme western end of Eurasia. The debate heated up a bit last year with the suggestion that a fossil skull from Yunxian, China, might be a close connection of this ancestral group.

Focusing on one or two fossils at a time is the wrong approach. The last part of the Early Pleistocene has dozens of hominin localities, many of them considered “Homo erectus”, which really just means they lack some derived features found in later humans and Neanderthals. Very few have been well dated.

Some of them really were different lineages. Homo naledi, with its known sample much later in the Middle Pleistocene, must have had ancestors, possibly among the African fossils previously attributed to Homo erectus. This thread had already spun its own way before the N-D-M ancestors lived. Some other fossils from a million years ago may be near the ends of their own long threads, stories we don’t know yet.

For the survivors, who became Neandersovans or early African Homo sapiens, the important points of uncertainty are about connections. How much were groups in far-flung places genetically isolated? How frequent was long-distance dispersal of populations? How much did gene flow connect groups over time?

Populations can travel across thousands of kilometers in space more easily than surviving across thousands of years of time. Crossroads of ancient peoples may have existed almost anywhere. Especially Casablanca.

Notes: I praise the authors of this paper and previous work for their open access publications, which have enabled me to share many images of the fossils, stone tools, and contextual data with readers.

References

Daujeard, C., Geraads, D., Gallotti, R., Lefèvre, D., Mohib, A., Raynal, J.-P., & Hublin, J.-J. (2016). Pleistocene Hominins as a Resource for Carnivores: A c. 500,000-Year-Old Human Femur Bearing Tooth-Marks in North Africa (Thomas Quarry I, Morocco). PLOS ONE, 11(4), e0152284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152284

Hublin, J.-J., Lefèvre, D., Perini, S., Muttoni, G., Skinner, M. M., Bailey, S. E., Freidline, S., Gunz, P., Rué, M., El Graoui, M., Geraads, D., Daujeard, C., Davies, T. W., Kupczik, K., Imbrasas, M. D., Ortiz, A., Falguères, C., Shao, Q., Bahain, J.-J., … Mohib, A. (2026). Early hominins from Morocco basal to the Homo sapiens lineage. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09914-y

Raynal, J.-P., Sbihi-Alaoui, F.-Z., Mohib, A., El Graoui, M., Lefèvre, D., Texier, J.-P., Geraads, D., Hublin, J.-J., Smith, T., Tafforeau, P., Zouak, M., Grün, R., Rhodes, E. J., Eggins, S., Daujeard, C., Fernandes, P., Gallotti, R., Hossini, S., & Queffelec, A. (2010). Hominid Cave at Thomas Quarry I (Casablanca, Morocco): Recent findings and their context. Quaternary International, 223–224, 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2010.03.011

Raynal, J.-P., Sbihi-Alaoui, F.-Z., Mohib, A., El Graoui, M., Lefèvre, D., Texier, J.-P., Geraads, D., Hublin, J.-J., Smith, T., Tafforeau, P., Zouak, M., Grün, R., Rhodes, E. J., Eggins, S., Daujeard, C., Fernandes, P., Gallotti, R., Hossini, S., Schwarcz, H. P., & Queffelec, A. (2011). Contextes et âge des nouveaux restes dentaires humains du Pléistocène moyen de la carrière Thomas I à Casablanca (Maroc). Bulletin de La Société Préhistorique Française, 108(4), 645–669.

I've been reading your work for a few years now, but only recently (today, in fact!) became a paid subscriber. As you write in the intro to this post, our ancestor populations had "tendrils [that] spanned Africa, Europe, and Asia." I'm curious, given what we know about our evolutionary history (and given what we can, perhaps, surmise or guess based on this knowledge), if you were to lead a global tour designed to tell the story of human evolution, to what places and to what sites would you take people? Let's assume this tour can't be exhaustive, and the purpose is to try to fashion some sort of coherent story of our evolutionary past for nonspecialists.