Expanding the “Cradle of Humankind”

Developing a broader idea of the habitats and capacities of early hominins

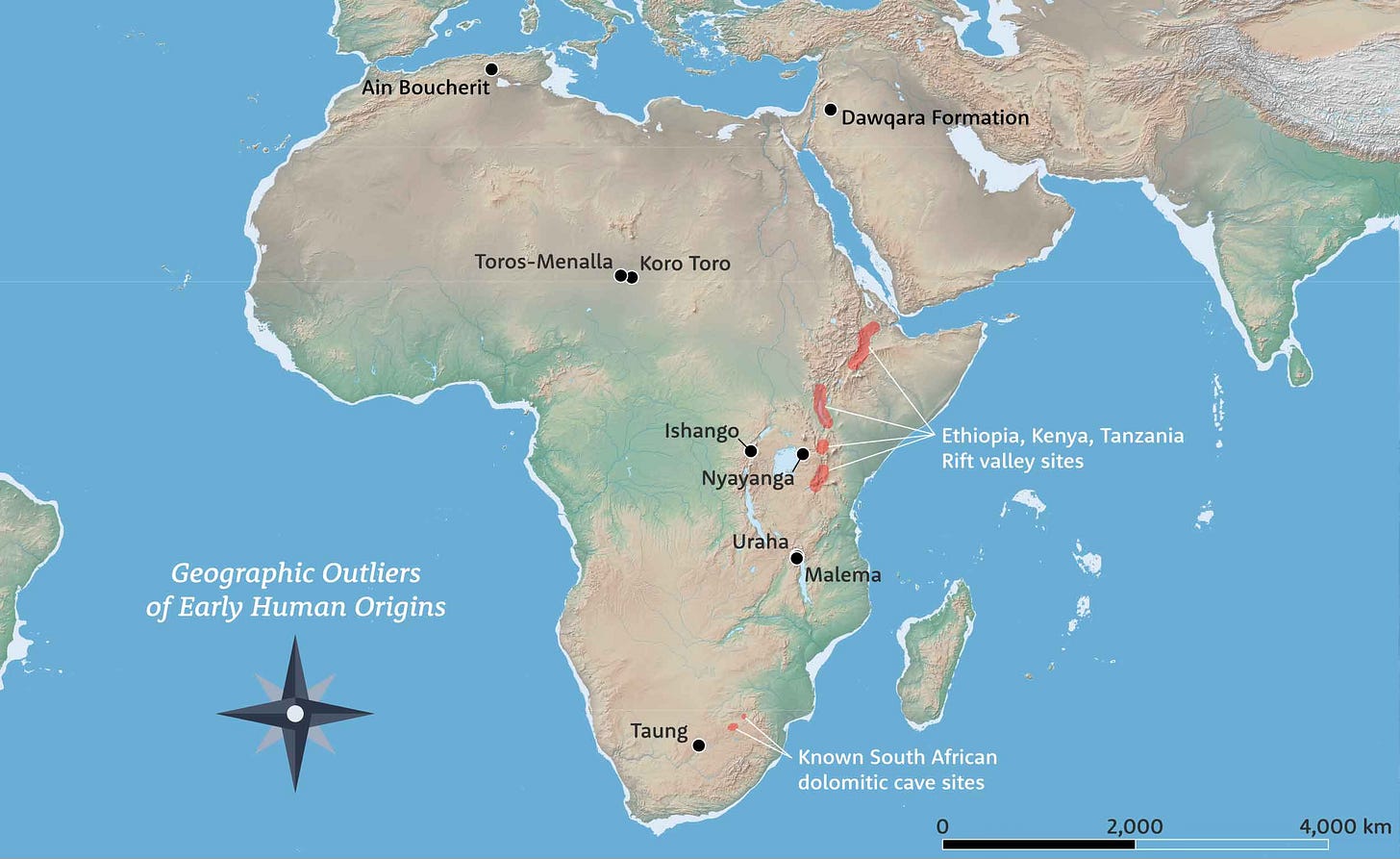

Anthropologists have found hundreds of hominin fossils from before two million years ago, representing twelve or more species. It’s an impressive haul. Yet almost all this evidence has come from only two geographic regions: the dolomitic cave systems of South Africa and the sedimentary exposures of the East African Rift System within Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania.

These narrow windows cover at most one percent of the 35-million-square-kilometer area of the African continent.

To be sure, these two areas tell us intricate local stories of climate change, animal and plant communities, altitude and water availability. But scientists’ ability to project beyond these local stories to understand the big picture is limited.

Every textbook discusses the reasons why these two areas have yielded so many fossil discoveries. The downward ratcheting of Earth’s crust within the East African Rift System has given rise to rivers and large lakes, preserving fossils within sedimentary layers and later yielding them up to erosion. The dolomitic caves of South Africa were habitats for ancient hominins and predators, keeping their bones like time capsules across millions of years. Still, these geological circumstances are not unique. Many other parts of Africa have favorable situations for the formation of fossil and archaeological sites.

I want to feature a few places beyond the usual areas where early hominins have been found. Some of them are within the East African Rift System, but in areas like Malawi that have received less attention. Others are thousands of miles away, like the Djurab Desert of Chad. I’m calling them geographic outliers. I’m focusing here on sites earlier than 2 million years ago that all help to expand the old idea of the “Cradle of Humankind”.

Chiwondo Beds

The most well-known discoveries from the East African Rift System are from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania, but the system continues farther toward the south. The Malawi Rift is the host geology of Lake Malawi today, and near the current lake’s northwestern shore is a sedimentary sequence known as the Chiwondo Beds. The deposits represent times as early as 4.3 million years ago, and as recently as 600,000 years ago. Subsequent deposits are represented in the area in the Middle and Late Pleistocene Chitumwe Beds.

Frank Dixey, a British colonial geologist, surveyed the geology of this area in the 1920s and 1930s recognizing the archaeological potential, which was followed up by several archaeologists. In the 1960s the archaeologist J. Desmond Clark worked in the area, characterizing several sites including some at Uraha Hill.

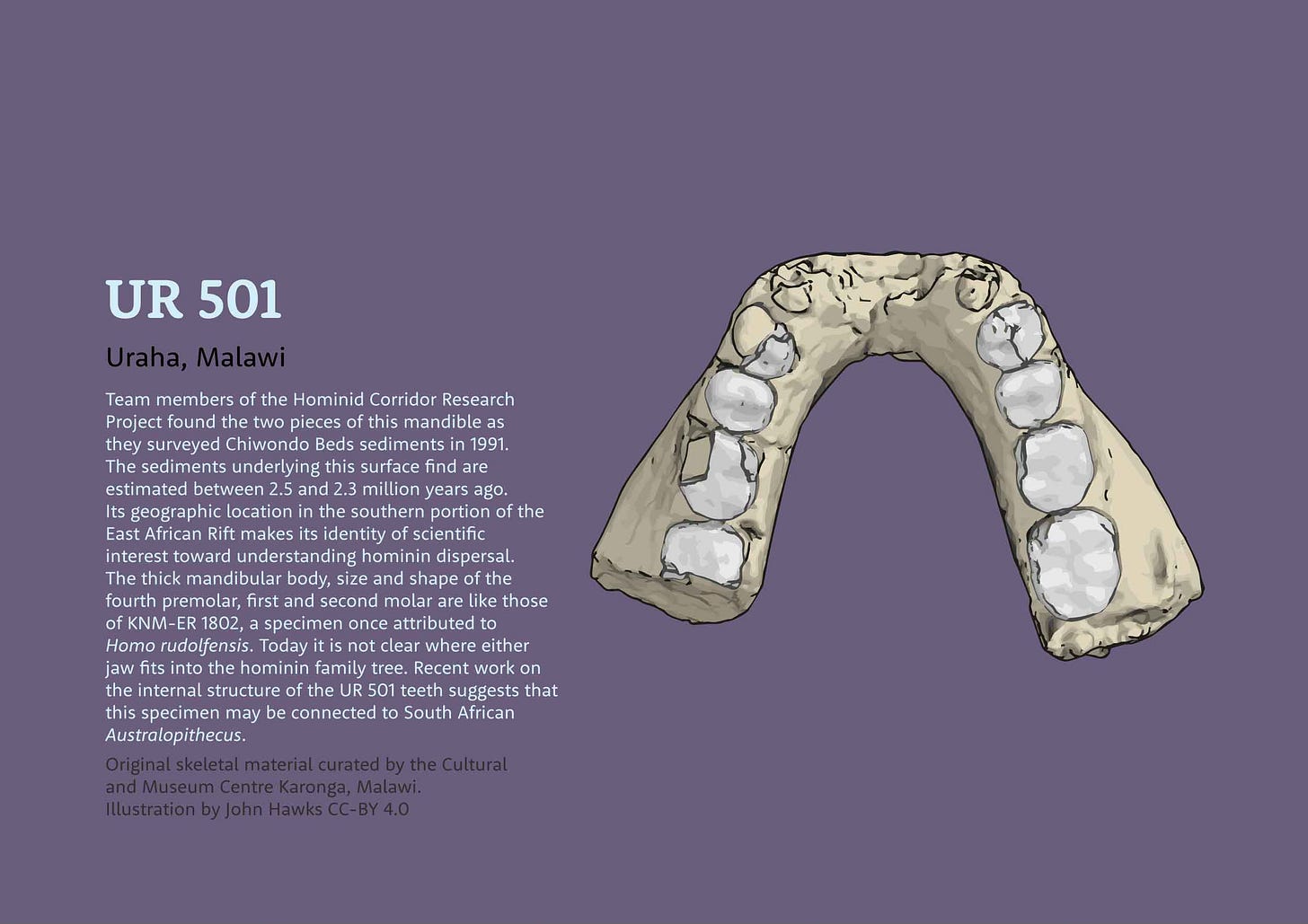

It was at Uraha that the first fossil hominin discovery was made by a team led by Friedemann Schrenk in 1991. The UR 501 fossil is a partial mandible dating to around 2.4 million years ago. The team suggested that the jaw is an early representative of Homo, emphasizing its similarity to the KNM-ER 1802 jawbone from Koobi Fora, estimated around 1.9 million years old. Later work by Clément Zanolli has suggested that the jaw may better be attributed to Australopithecus; the size and form of its teeth and mandibular corpus lie in the range of overlap of the two genera.

Schrenk and collaborators have identified two other sites from the Chiwondo Beds with hominin fossil material. The Malema site has a partial maxilla, HCRP RC 911, with massive molars characteristic of Paranthropus boisei. A nearby site, Mwenirondo, has produced a partial molar attributed to Homo. These sites are of roughly similar age to the Uraha Hill hominin mandible.

The Chiwondo Beds sites are located roughly halfway between the hominin sites of northern Tanzania and the caves of South Africa. They provide an opportunity to look at the connections between these regions. The presence of P. boisei in this area tends to reinforce that a biogeographic boundary between South African Paranthropus robustus and East African P. boisei may have existed south of the Malawi Rift.

Nyayanga

Lake Victoria formed upon a high plateau that separates the two main branches of the East African Rift System, the Eastern and Western Rifts. The lake’s level more than 1100 meters above sea level is 500 meters higher than the floor of either rift, and its surface area is more extensive than North America’s Lake Huron. A peninsula juts into the lake near its northeast corner, formed by Mount Homa and its slopes.

The Homa Peninsula of Kenya has sedimentary deposits that formed across the last 2.6 million years as rivers flowed from the mountain’s slopes. The area has many valuable archaeological sites. The Kanjera area was a target of Louis Leakey during the 1930s, and much later from the 1980s excavations began at Kanjera South, where many localities preserve stone tools and animal bones from 2 million years ago or earlier.

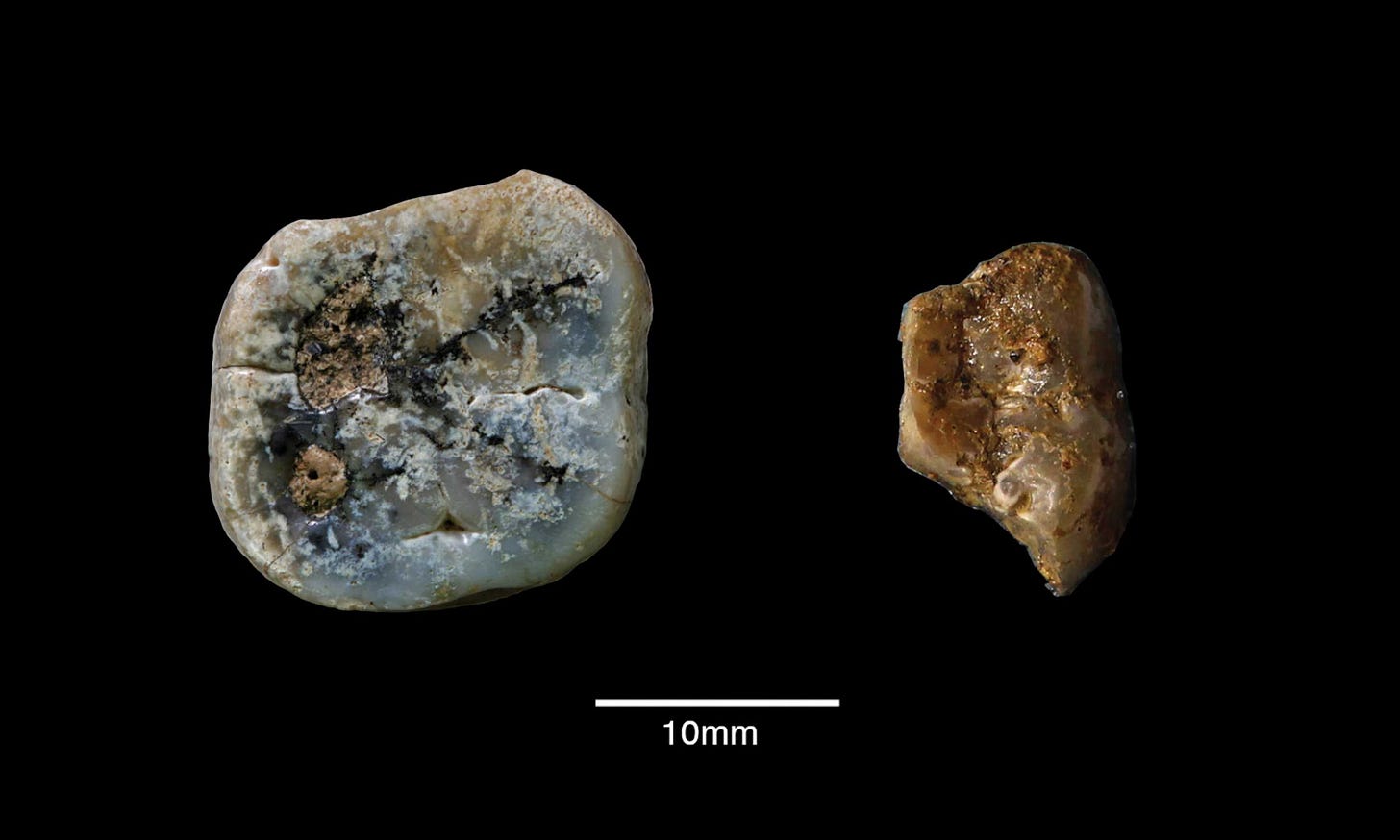

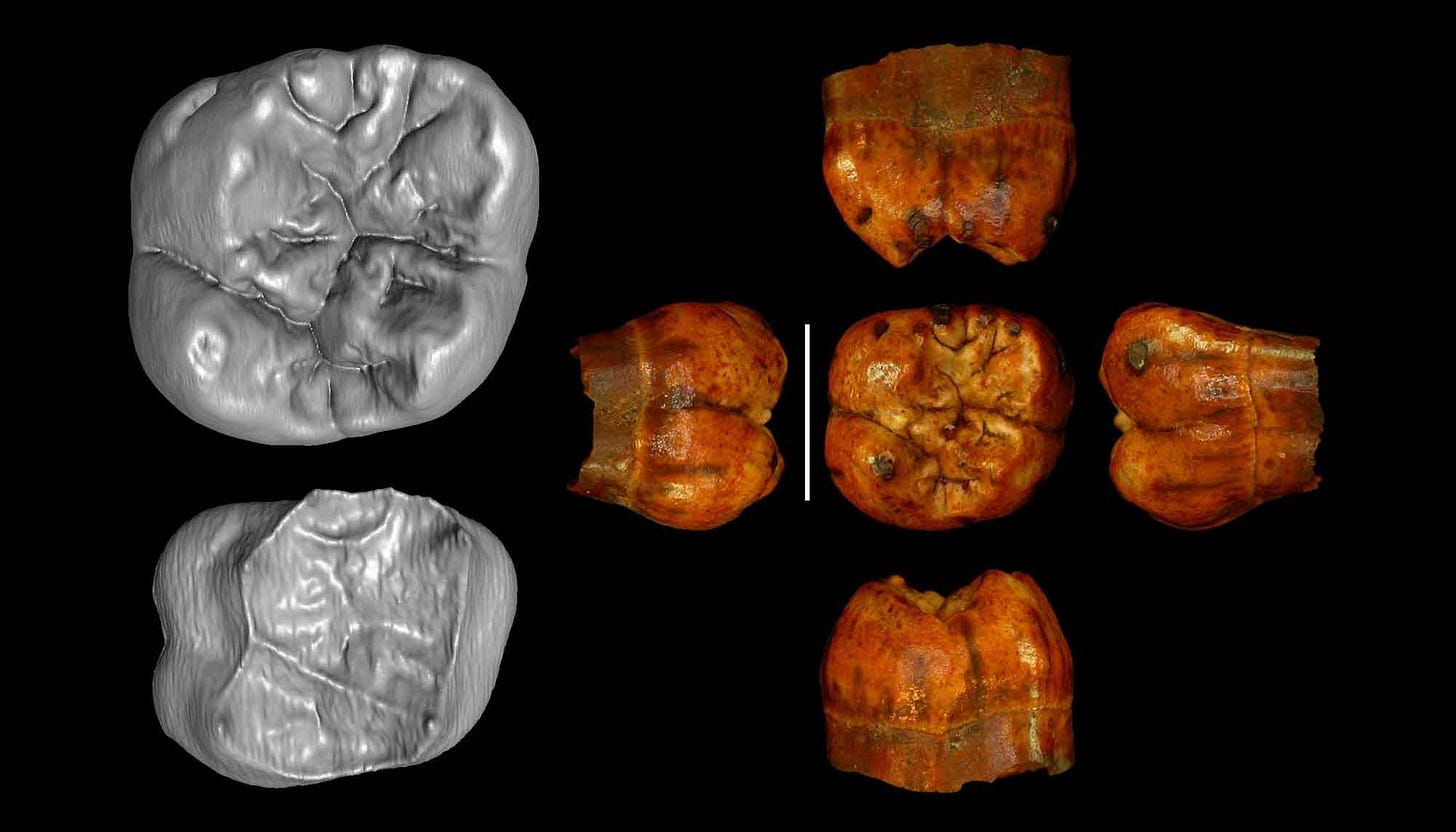

In 2023 Thomas Plummer and collaborators reported on work from a relatively small site called Nyayanga. This site formed between 3.0 million and 2.6 million years ago and preserves some of the earliest Oldowan stone tools, as well as animal bones with marks from ancient butchery, including a hippopotamus. This is currently the earliest site attributed to the Oldowan Industrial Complex.

The site also has two hominin teeth: an upper molar and a fragment of a lower molar. The teeth are large, and their form enabled Plummer and coworkers to identify them with the genus Paranthropus—although with such slim evidence, there is not enough to suggest whether they belong to an existing species like Paranthropus aethiopicus or whether they may be something new. These are the earliest examples of Paranthropus yet identified anywhere in Africa.

Ishango

North of Lake Malawi, the East African Rift System bifurcates into two branches. The Eastern Rift proceeds northward across central Tanzania and Kenya toward Lake Turkana. This branch is the one familiar to students of human evolution, studded with well-known fossil and archaeological sites from Isimila, Olduvai Gorge, and Laetoli in Tanzania, up through the Tugen Hills and Lake Turkana Basin in Kenya, then northeast toward the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia.

Starting from the northern end of Lake Malawi, the Western Rift arcs for a few hundred kilometers toward the center of the continent, forming the bed of Lake Tanganyika before turning northward against the eastern wall of the Virunga Mountains. At the northern shore of Lake Edward, the Semliki River exits flowing north toward Lake Albert. On the river’s western shore are sedimentary deposits with fossils and archaeology, near a small village and airport called Ishango.

Belgian paleontologists began to investigate these deposits in the 1930s. Their archaeological finds, including many bone harpoons, represent ancient people who lived in this region within the last 100,000 years. In the 1950s the geologist Jean de Heinzelin worked in the Ishango area, characterizing many archaeological and fossil sites, including a famous artifact known as the Ishango Bone, a counting device dating to around 20,000 years ago.

De Heinzelin recovered fossils from some sites that today are recognized in the span from 2.6 million to 2.0 million years old. One of those fossils, not recognized at the time of discovery, is a large molar of a hominin numbered #Ish25. Isabelle Crevecoeur and collaborators reexamined this tooth in a 2014 study, using methods that enabled them to look inside the tooth at its enamel-dentine junction. Their work shows that in size and form the tooth is similar to those attributed to Australopithecus or to early Homo.

Toros-Menalla

In the Djurab Desert of central Chad are a number of fossil sites, including the earliest attributed to any possible hominin. The Toros-Menalla area was investigated by members of the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Tchadienne starting in 2001. At a locality numbered as TM 266, the field team collected fossils from the surface including a skull of a hominoid, a mandible, and isolated teeth which Michel Brunet and coworkers named as Sahelanthropus tchadensis in a 2002 research article.

Over subsequent seasons of work in the Toros-Menalla area the researchers collected additional jawbones attributed to Sahelanthropus at other localities, TM 247 and TM 292, joining the fossils from TM 266. Work on the geological context of these sites showed that they all date to around 7 million years ago—more than double the age of the “Lucy” skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis.

In recent years some Sahelanthropus fossils have gained attention due to their omission from the early scientific record. The shaft of a femur and two ulnae recovered in the early days of exploration of Toros-Menalla were at last described in 2020 and 2022 by two teams, both indicating important differences from those of Australopithecus and other hominins. These bones suggest that the way that Sahelanthropus moved may have been quite different from most human relatives.

Was Sahelanthropus a human relative, or does it instead belong to another lineage of extinct apes? The evidence makes it hard to say.

The base of Toumaï’s skull does suggest that the individual kept a more vertical habitual posture than living great apes. The femur and ulnae are clearly well suited for climbing and quadrupedal movement. This mix doesn’t look like any of the hominins from the last four million years. But it might be more consistent with Ardipithecus. Certainly more evidence will be needed to understand the way that Sahelanthropus fit into its environment and into our family tree.

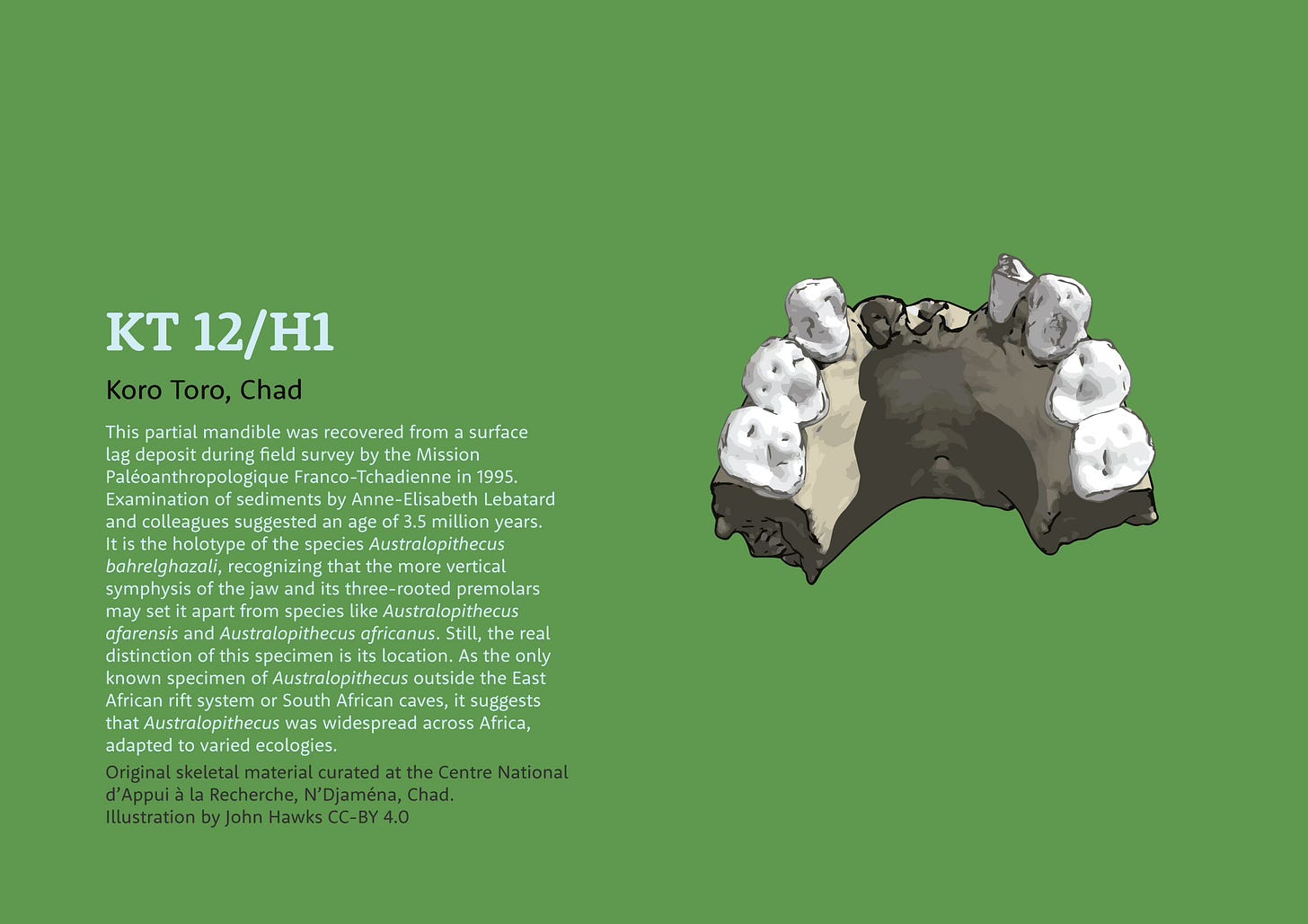

Koro Toro

Before researchers found Toumaï, they found Abel. Near the eastern extreme of the Djurab Desert is a settlement called Koro Toro, which today is the location of a maximum security prison. The Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Tchadienne in 1994 and 1995 surveyed fossil deposits to the west of Koro Toro, finding a number of places with fossils either on the surface or eroded from the underlying layers during the last highstand of Mega-Lake Chad. Some of those fossils were from a locality numbered KT12, including a partial hominin jaw and an isolated premolar, now estimated between 3.8 million and 3.2 million years old. Michel Brunet nicknamed the jaw with the Biblical name, “Abel”.

The KT12 jaw is very similar to jawbones of Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, in most ways. But a couple of details differ, including its three-rooted third premolars and a less sloping, more vertical chin region. Brunet and collaborators proposed recognizing the jaw as a different species, Australopithecus bahrelghazali. Many researchers continue to recognize the fossil within A. afarensis, already known from sites across Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania from the same time period.

Further work by the team uncovered additional hominin jaw fragments from two other localities, KT13 and KT40. Data from these fossils has appeared in a handful of studies, but the fossils remain unpictured and undescribed, nearly thirty years after discovery.

Taung

It may seem out of place for me to list one of the best-known hominin fossils as an outlier. But the Taung site, in South Africa’s Northwest Province, is different in important ways from the dolomitic caves in which many other South African fossils occur.

The hominin fossil skull from Taung was found within the breccia of a tufa cave, the only fossil hominin from such a context. Tufa is formed when groundwater emerges from springs, enabling dissolved carbon dioxide to escape and causing dissolved calcium carbonate to precipitate into layers. These layers can give rise to natural cavities and caves either while they are forming or after the springs move and they are exposed to rainfall and dissolution.

The story of the skull’s discovery in 1924 has been told many times, including by me. The fossils were recognized by a workman in the process of intensive quarrying of the tufa deposits, and conveyed to Raymond Dart by rail shipment by the geologist R. B. Young. It took a very long time to come to an appreciation of the skull’s context, which was destroyed by the mining. The geological age of the skull is now thought to be older than 3 million years. Periodically new teams of geologists return to the question to find new clues from the fossil or site.

Evidence without fossils

Beyond fossil bones and teeth there are other sources of evidence showing the presence of human ancestors outside the well-known fossil regions. Stone tools are one of these kinds of evidence.

Every stone tool is a sign that somebody was once present. But who? Decades ago, archaeologists often presumed that stone tools were only produced by the genus Homo, making them a kind of type fossil of our genus. That hasn’t been true for a long time. Early stone tools have been found in contexts with fossils of many kinds of hominins, and the anatomy and dietary evidence of both Paranthropus and Australopithecus suggest that they sometimes included tools within their foraging activities. So tools without fossils don’t tell us which hominins were present.

At or before two million years ago, there are a few geographic outlier sites where stone tools have been found, but without hominin fossils—at least, not yet.

Kanjera South, Kenya, near the Nyayanga site, is an area with abundant early archaeological finds, estimated at just around 2 million years of age.

Ain Boucherit, Algeria. This site is around 50 km from the present Mediterranean coastline. The Oldowan stone artifacts and cutmarked animal bones include some dating to around 2.4 million years ago.

Dawqara Formation, Jordan. In the valley of the Zarqa River northeast of Amman, the Early Pleistocene Dawqara Formation dates to between 2.5 and 2.0 million years ago. Stone artifacts from this formation attest the presence of Oldowan-making hominins.

The presence of hominins along the Mediterranean coast of North Africa and into the Levant before 2 million years ago is fascinating. So far, no one knows which species may have been present there.

Adding to the map

Among the fossils from these outlier sites are the holotypes of three hominin species—two of which have only been found at the outlier sites where they were first discovered. They represent diversity that has been seen nowhere else. They are some of the most valuable hints of how widespread hominins were, and what environments they could inhabit.

In the time after two million years ago, scientists have found more fossils. Starting by 1.8 million years, the record includes hominins from Eurasia. Still, within Africa the East African Rift System and South African caves provide most of the evidence, well into the last million years when a broader geographic range of sites start to become important.

Lots of times people ask me, why haven’t archaeologists or anthropologists done more to survey some of the broader parts of Africa that might have been home to ancient humans or their ancestors?

The stories that people may read about fossil discoveries don’t often convey what it takes to add to the hominin record. Even paleontologists themselves tend to focus in their stories mostly on the moment of discovery. Nobody wants to hear about all the times they went to the field, worked hard, and didn’t find as much as they hoped.

That’s a reason why I’ve pointed here to some of the early history of exploration at these geographic outlier sites, which often started in the 1920s or 1930s. Archaeologists have spent a lot of time surveying places with favorable geology, identifying interesting sites in the process. In a few cases a hominin discovery was made early in the site’s history. In others, it took long years of follow-up work.

There are many more fossils out there to find. Broadening the map will take sustained effort. The parts of the map with many discoveries are places where scientists today have developed sustainable collaborations for field and laboratory research.

Imagine what diversity of extinct human relatives may have existed in other parts of Africa! That’s one of the questions that keeps me going. We need to do everything we can to open new windows into the crucial times and places of our ancestors’ evolution.

Notes: One site I didn’t discuss above is the possible footprint site of Trachilos, on the island of Crete. I’ll be writing up another post looking at the most recent updates on that site and its geology.

Several other archaeological sites in Eurasia possibly predate 2 million years ago. Stone tool occurrences at Riwat, Pakistan, Ain al Fil, Syria, and Yiron, Israel all have been suggested at ages up to 2.4 million years ago or more. In each case there are arguments that the context of the artifacts was inadequate to ensure they were not somewhat more recent. The ability to assess such early sites continues to grow.

It’s quite often the case that I’m frustrated when I don’t have great images to share for sites and fossils. This post hit me more than most because of how few site images are available, none with licenses that can be shared. Thank goodness for NASA’s archive.

References

Brunet, M., Beauvilain, A., Coppens, Y., Heintz, E., Moutaye, A. H. E., & Pilbeam, D. (1995). The first australopithecine 2,500 kilometres west of the Rift Valley (Chad). Nature, 378(6554), Article 6554. https://doi.org/10.1038/378273a0

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Mackaye, H. T., Likius, A., Ahounta, D., Beauvilain, A., Blondel, C., Bocherens, H., Boisserie, J.-R., De Bonis, L., Coppens, Y., Dejax, J., Denys, C., Duringer, P., Eisenmann, V., Fanone, G., Fronty, P., Geraads, D., … Zollikofer, C. (2002). A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature, 418(6894), Article 6894. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00879

Cazenave, M., Pina, M., Hammond, A. S., Böhme, M., Begun, D. R., Spassov, N., Gazabón, A. V., Zanolli, C., Bergeret-Medina, A., Marchi, D., Macchiarelli, R., & Wood, B. (2025). Postcranial evidence does not support habitual bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis: A reply to Daver et al. (2022). Journal of Human Evolution, 198, 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103557

Daver, G., Guy, F., Mackaye, H. T., Likius, A., Boisserie, J.-R., Moussa, A., Pallas, L., Vignaud, P., & Clarisse, N. D. (2022). Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad. Nature, 609(7925), Article 7925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04901-z

de Heinzelin, J. (1962). Ishango. Scientific American, 206(6), 105–118.

Kullmer, O., Sandrock, O., Kupczik, K., Frost, S. R., Volpato, V., Bromage, T. G., & Schrenk, F. (2011). New primate remains from Mwenirondo, Chiwondo Beds in northern Malawi. Journal of Human Evolution, 61(5), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.07.003

Parenti, F., Varejão, F. G., Scardia, G., Okumura, M., Araujo, A., Ferreira Guedes, C. C., & Neves, W. A. (2024). The Oldowan of Zarqa Valley, Northern Jordan. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-023-00168-6

Plummer, T. W., Oliver, J. S., Finestone, E. M., Ditchfield, P. W., Bishop, L. C., Blumenthal, S. A., Lemorini, C., Caricola, I., Bailey, S. E., Herries, A. I. R., Parkinson, J. A., Whitfield, E., Hertel, F., Kinyanjui, R. N., Vincent, T. H., Li, Y., Louys, J., Frost, S. R., Braun, D. R., … Potts, R. (2023). Expanded geographic distribution and dietary strategies of the earliest Oldowan hominins and Paranthropus. Science, 379(6632), 561–566. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo7452

Sahnouni, M., Parés, J. M., Duval, M., Cáceres, I., Harichane, Z., van der Made, J., Pérez-González, A., Abdessadok, S., Kandi, N., Derradji, A., Medig, M., Boulaghraif, K., & Semaw, S. (2018). 1.9-million- and 2.4-million-year-old artifacts and stone tool–cutmarked bones from Ain Boucherit, Algeria. Science, 362(6420), 1297–1301. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau0008

Schrenk, F., Bromage, T. G., Betzler, C. G., Ring, U., & Juwayeyi, Y. M. (1993). Oldest Homo and Pliocene biogeography of the Malawi Rift. Nature, 365(6449), 833–836. https://doi.org/10.1038/365833a0

> well into the last million years when a broader geographic range of sites start to become important.

I think statistics for Eurasian fossils began to pick up after 1.5 mY ago, and stays on par with the African one for any large time period, and after 500 kY leads the African one. At least if one too quantify the list from here, for example https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_human_evolution_fossils

It is not complete, of course, but I think it represents the trend reasonably well

Great article! Thanks for your insights. It’s difficult for an enthusiast to keep up with everything going on in your field.