How Sahelanthropus tchadensis moved

Not quite like a hominin, but with extended hip posture similar to Ardipithecus ramidus

I’ve been trying to understand the fossils of Sahelanthropus tchadensis since Michel Brunet led a team in describing its skull—nicknamed Toumaï—back in 2002.

This fossil skull and all other known fossils of S. tchadensis come from the Djurab desert of Chad, where they lived an estimated 7 million years ago. Many accept S. tchadensis as the earliest hominin. But unanswered questions have left some scientists skeptical.

I’ve been one of the skeptics.

One of the most contentious issues has been locomotion. Today, we’re coming closer to an understanding of the early adaptations to upright walking in our relatives. After being hidden for almost two decades, the partial femur and two ulnae of S. tchadensis have now started to clarify how this species compares with known hominins like Australopithecus, as well as with living and extinct apes.

This story has changed a lot over the years. With today’s much better genetic information about human and chimpanzee relationships, the stakes of the question have also changed. Sahelanthropus tchadensis may be just one window into a network of populations that exchanged genes as the human lineage slowly differentiated from our closest relatives.

History of the problem

Did S. tchadensis walk upright? For almost twenty years, the Toumaï skull seemed to be the only evidence. The cranial base and back of the cranium can be informative about posture and movement, but both areas were badly distorted in the course of fossilization. Researchers led by Christoph Zollikofer who reconstructed the skull from CT scans in 2005 suggested it was configured like early hominins, including Australopithecus.

Working with several collaborators, I challenged this interpretation—first in a 2002 comment and then in a longer 2006 research article. One area that impressed us was Toumaï’s elongated attachment area for muscles of the neck, much more like great apes than hominins. To be sure, S. tchadensis shares traits with hominins like Australopithecus—for example, canines worn on the tip instead of the blade-like wear seen in many living apes. But traits like this can also be found in other long-extinct apes. We observed that across the decades many fossils had a similar story: at first interpreted as human relatives, later shown to be extinct apes.

More bones were needed. If none had ever turned up, I’m not sure I’d have much more to say about S. tchadensis today.

But new evidence did turn up, from an unexpected quarter. Just at the time of discovery of the Toumaï skull, members of the same field team also collected a femur shaft and a partial ulna of S. tchadensis at the same locality. Six months later, they found a second ulna fossil.

These could have been gamechangers—if anybody could have seen them. But for eighteen years, they remained undescribed.

The journalist Scott Sayare related the weird story of these fossils last year in a fascinating article for The Guardian. Accounts differ on why Brunet and collaborators omitted these bones from their 2002 description of S. tchadensis and their subsequent 2005 article in which they described two additional mandibles and several teeth recovered from nearby sites. Since posture and locomotion were so important to understanding S. tchadensis, leaving out these bones was a bad scientific decision.

From the first time I saw photos of the femur, I knew it would not be easy to interpret how it functioned. I wrote as much back in 2009 when I was able to share some photos with my readers, courtesy of Aude Bergeret-Medina, who had examined the fossil. I hardly guessed at the time that another decade would pass before I learned any more about it.

Things changed in 2020, when Guillaume Daver and coworkers described the femur and two ulnae in a preprint. Their work, later published in Nature, concluded: “The Toros-Ménalla femur exhibits several hallmarks of selection for bipedalism as a regular behaviour”.

At around the same time, the Journal of Human Evolution released a peer-reviewed article by Roberto Macchiarelli and coworkers, presenting their own interpretation of the femur’s anatomy: “there is no compelling evidence that it belongs to a habitual biped”.

Pretty stark difference.

Whenever fossils are interpreted differently by different groups of smart people, I go looking for an explanation. Often the problem is that one or both groups do not have access to all the data. So I’ve been following the research closely to try to puzzle out the truth.

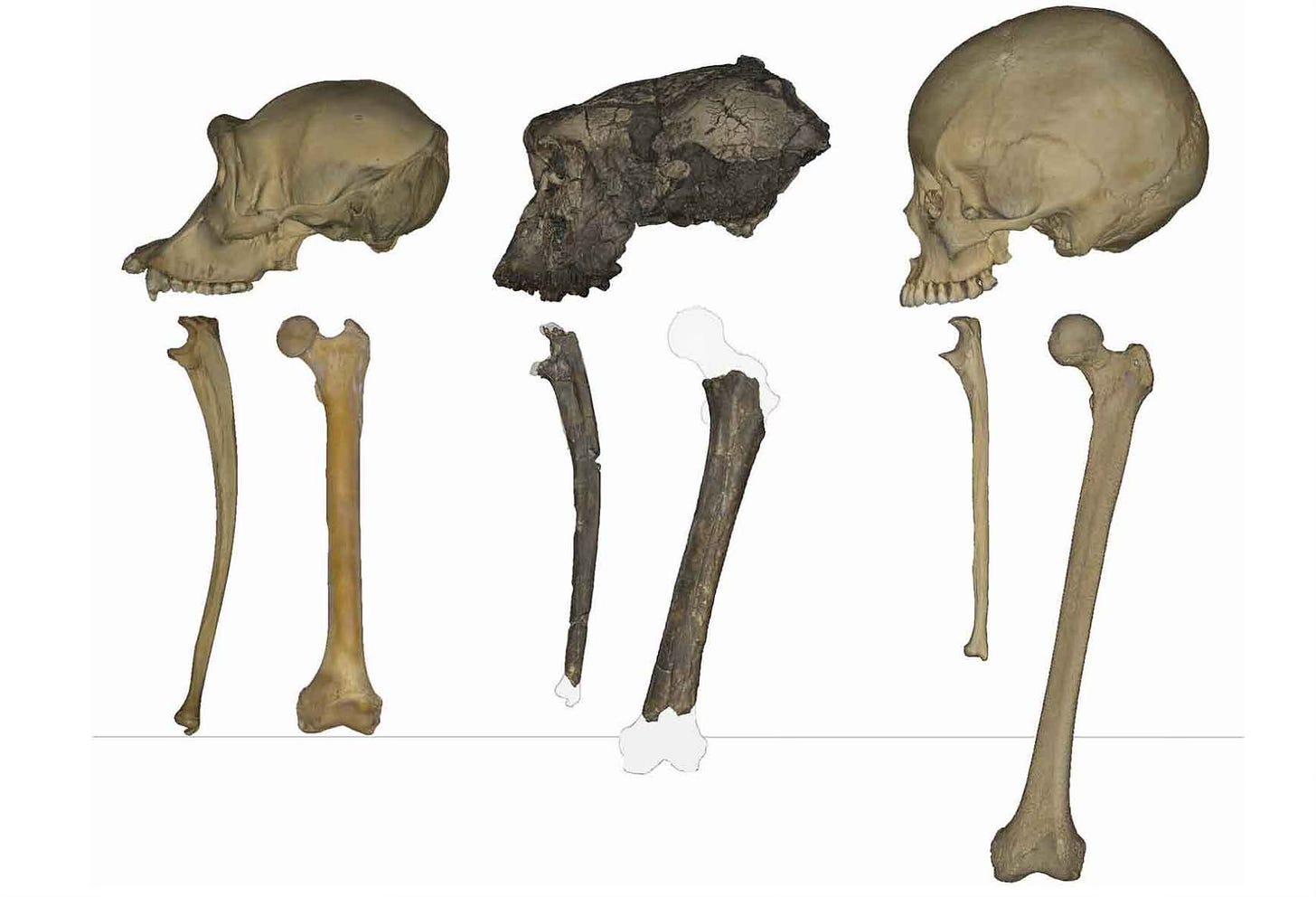

A recent study led by Scott Williams in Science Advances has been helpful. Williams’ team was able to scan and analyze high resolution replicas of the bones, held at Harvard University. Looking at them in person yielded insight into some features that earlier studies had overlooked. With their scans, they also built a better idea of the relative sizes of the bones and their comparisons with other species of apes and hominins.

The most valuable thing about their paper is that Williams and coworkers have provided clear illustrations of the fossils, together with close comparisons with other species. While I’ve read earlier papers closely, the illustrations left much to be desired, and to be quite honest in most cases I don’t think they have shown the fossils in enough detail for me to assess whether they’ve described them accurately. The open access license of Williams’ and collaborators’ work lets me configure those here for readers.

The femur

You wouldn’t think it would be that hard to look at a femur and tell whether an ape was a biped. But most of the things that work for human legs also have to work for ape legs. All living apes can and do stand and walk bipedally—they just aren’t tuned for it to the exclusion of other forms of movement, as humans are. Of the features that set human femora apart from the living great apes, some relate to our taller stature and longer legs. Many hominins like Australopithecus were pretty different from living people in leg length and stature, so their patterns of femoral anatomy were not quite the same as today’s people.

Because of the diversity among bipedal hominins, it takes more than comparing humans and apes to understand how the femoral anatomy of an extinct species related to their pattern of movement. It takes careful attention to muscle and joint function.

Apes tend to keep knees slightly bent when they stand upright. When they walk bipedally, it is with less hip extension, less knee extension, and without the distinctive toe-off of a human stride. They rarely run bipedally, although they may rear up on two legs when charging forward at another individual.

Bipedal walking and running in hominins like Australopithecus involved functional innovations in the hip joint and knee joint. Walking with a more extended hip required massive alterations to the pelvis. The changes to the femur were more subtle. The knee is most strongly involved: Australopithecus had slightly flattened femoral condyles sitting at a distinct angle from the shaft. The femur neck of Australopithecus is longer and angles more forward—called femoral neck anteversion—than in apes. The femur neck is flatter from front to back, orienting the cortical bone and internal trabecular structure to resist vertical force. Several ligament and tendon attachments of the proximal femur important to bipeds also have bony traces, especially involving the gluteus muscles and the iliofemoral ligament.

These are the features I would point out to any introductory student in my courses. As important as they are, neither the distal end nor femoral head and neck are well-preserved in the S. tchadensis femur TM 266-01-063. This is why I had very little to say about the shape from the photos of the specimen. The dark coloration of the specimen also makes photos hard to interpret. What was needed was for someone to make the data available.

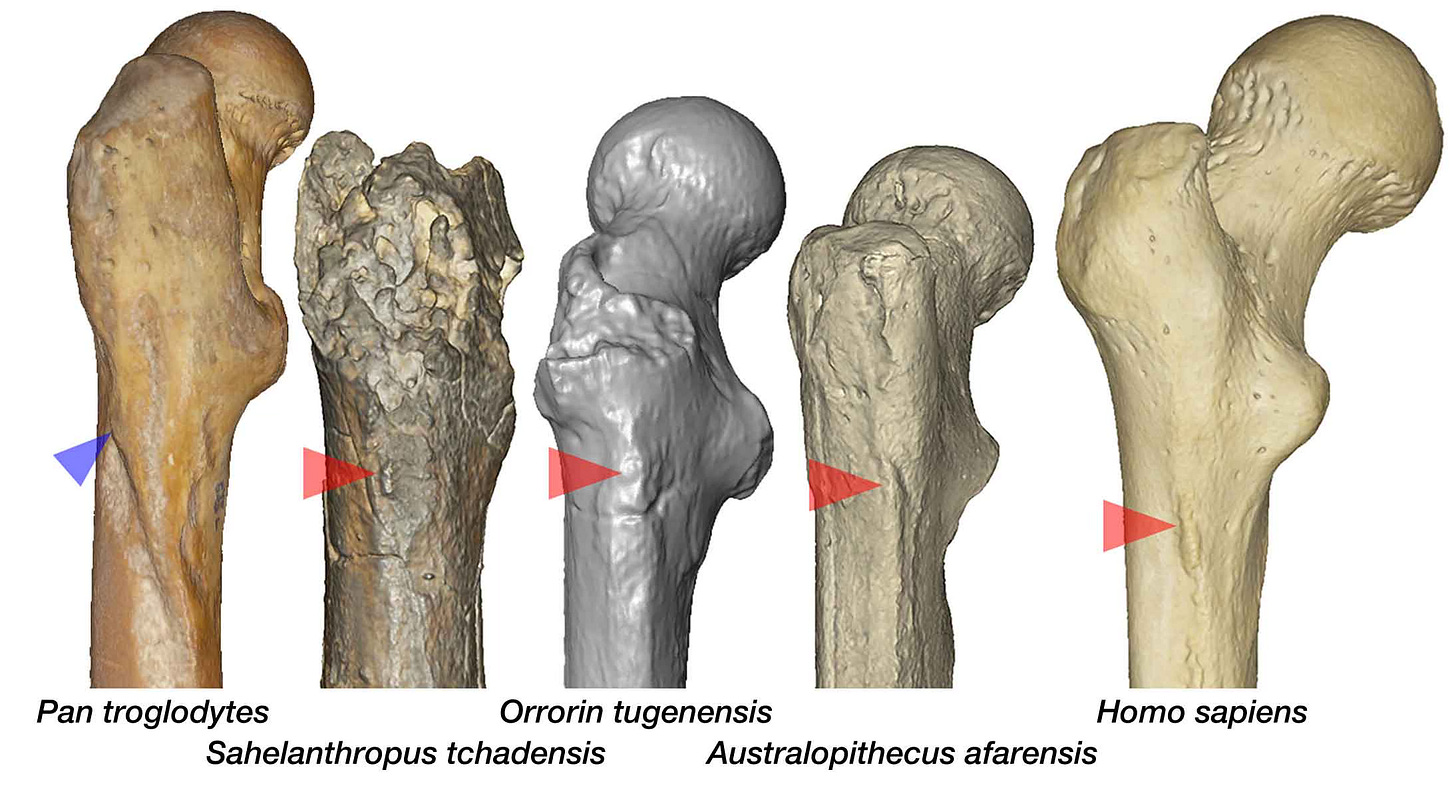

Daver and coworkers pointed out that the base of the femoral neck of the TM 266-01-063 femur seems to have a flatter, or anteroposteriorly compressed nature, similar to humans but also to Miocene apes like Danuvius guggenmosi. Just at the edge where the bone is broken, Williams and coworkers observe a small bump, which they identify as the femoral tubercle. That’s an attachment site for the iliofemoral ligament, which stabilizes the hip joint when the leg is extended. It’s seen in humans and other bipedal hominins, but not in great apes.

The shaft of the femur also matters to bipedal walking. Near its proximal end, humans and chimpanzees differ in muscle attachment configuration. Humans and Australopithecus have a gluteal tuberosity or roughened ridge for attachment of the gluteus maximus, while chimpanzees and other great apes have a more anterior insertion for this muscle with a smooth, more rounded ridge descending from it, called a spiral pilaster. All the researchers who have examined TM 266-01-063 have paid attention to this area, and they express diverging opinions: the papers led by Scott Williams and Guillaume Daver say it’s hominin-like, the papers led by Roberto Macchiarelli and Marine Cazenave say it’s ape-like.

Well, from Williams’ illustrations, I can see what both sides have been seeing. In the image above the red arrows point to gluteal tuberosity, including the bump that Williams and coworkers interpret as this feature in TM 266-01-063. The spiral pilaster curving down the side of the chimpanzee femur is pretty clear in this view. The complication is that the TM 266-01-063 femur appears to have a angled fracture or stress line that almost parallels the spiral pilaster of the chimpanzee. Looking at a photograph and not a 3D replica or scan, I can see how someone might misinterpret the shape here.

I believe I’ve mentioned many times that secrecy and closed access to scans does nothing but hold back scientific work. I have found that the easiest way to get other researchers to see what you are describing is to simply give everyone the data.

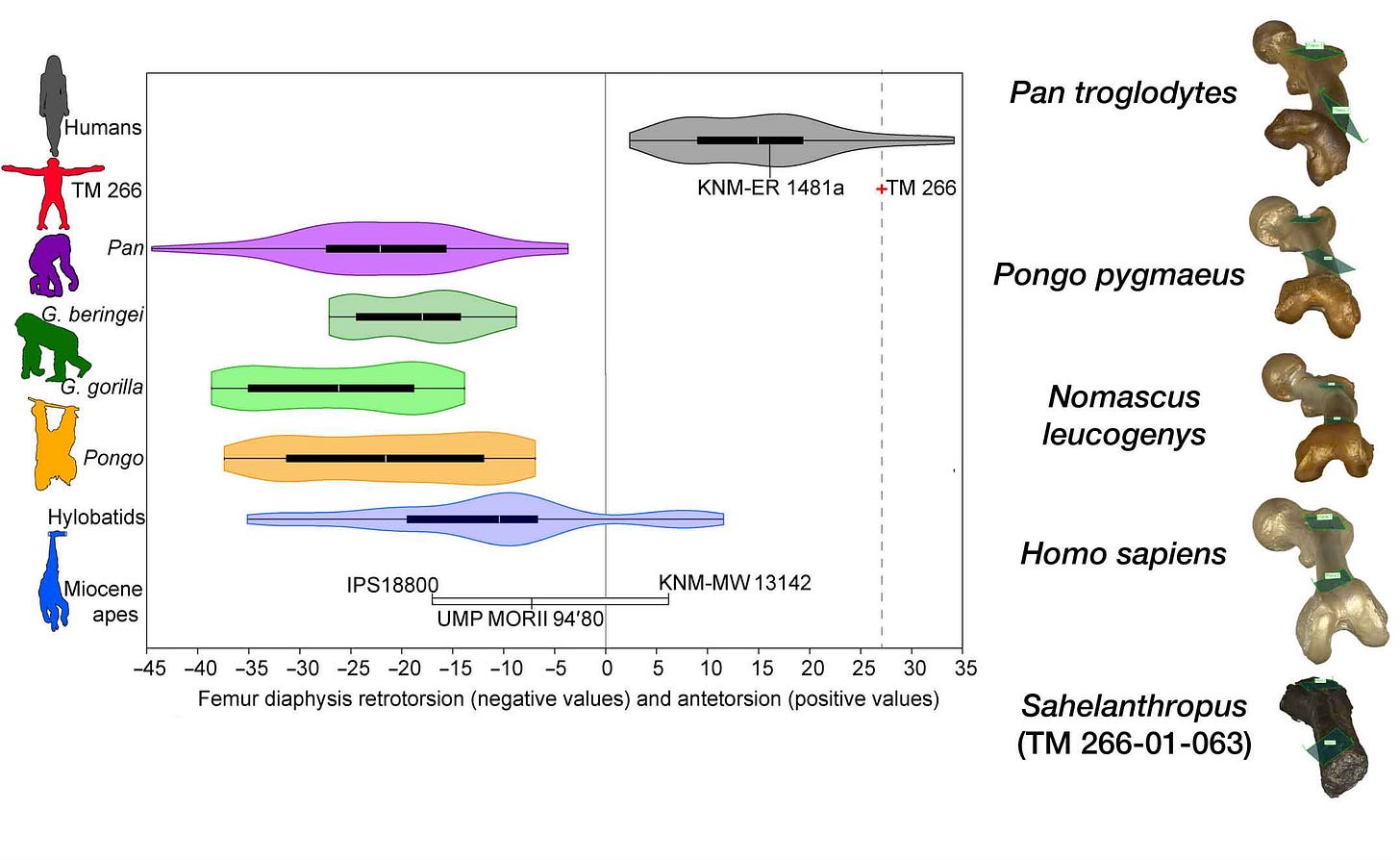

Another thing that is hard to see in a photograph is how twisted the shaft is. The angle between the femoral neck and femoral condyles is positively twisted—neck more forward—in humans, and neutral or negatively twisted—neck to the side—in great apes. That twist is manifested at the base of the femoral neck and the proximal femoral shaft. In S. tchadensis, Williams and coworkers find that the twist is more human than most humans.

Together with the muscle and ligament attachments, that’s a fairly good argument for weight support with an extended hip. The earlier study by Daver and coworkers included data from CT scanning, enabling them to observe the bone tissue inside the femur. A key observation in that study was an alignment of the trabecular bone plates known as the calcar femorale, often found in humans and rarely observed with a similar form in living great apes.

Still, extended hip posture doesn’t necessarily mean Australopithecus-like bipedality. The mention of Danuvius above is a hint that many of these features do overlap either with extinct apes or with the range of variation within living great apes.

The mechanics coming into focus from the TM 266-01-063 femur are generally compatible with the way that Owen Lovejoy, Tim White, and collaborators have described the femoral anatomy of Ardipithecus ramidus. It’s a pity that there isn’t more overlap between the preserved portions of the femur in Ar. ramidus and S. tchadensis. Lovejoy and coworkers do picture the femoral fragment designated ARA-VP-1/701, an isolated find that has a similar gluteal tuberosity morphology, continuing toward what Lovejoy termed a “proto-linea aspera”. With a fairly flat separation of the attachments of the vastus group from the adductor group, it’s different from the pronounced, rough line in humans.

Summarizing their observations, Williams and coworkers describe the Sahelanthropus femoral morphology as reflecting “a non-obligatory terrestrial biped that retained powerful hip extension for flexed hip locomotor behaviors such as vertical climbing”.

“Sahelanthropus may represent an early form of habitual, but not obligate, bipedalism.”—Scott Williams and coworkers

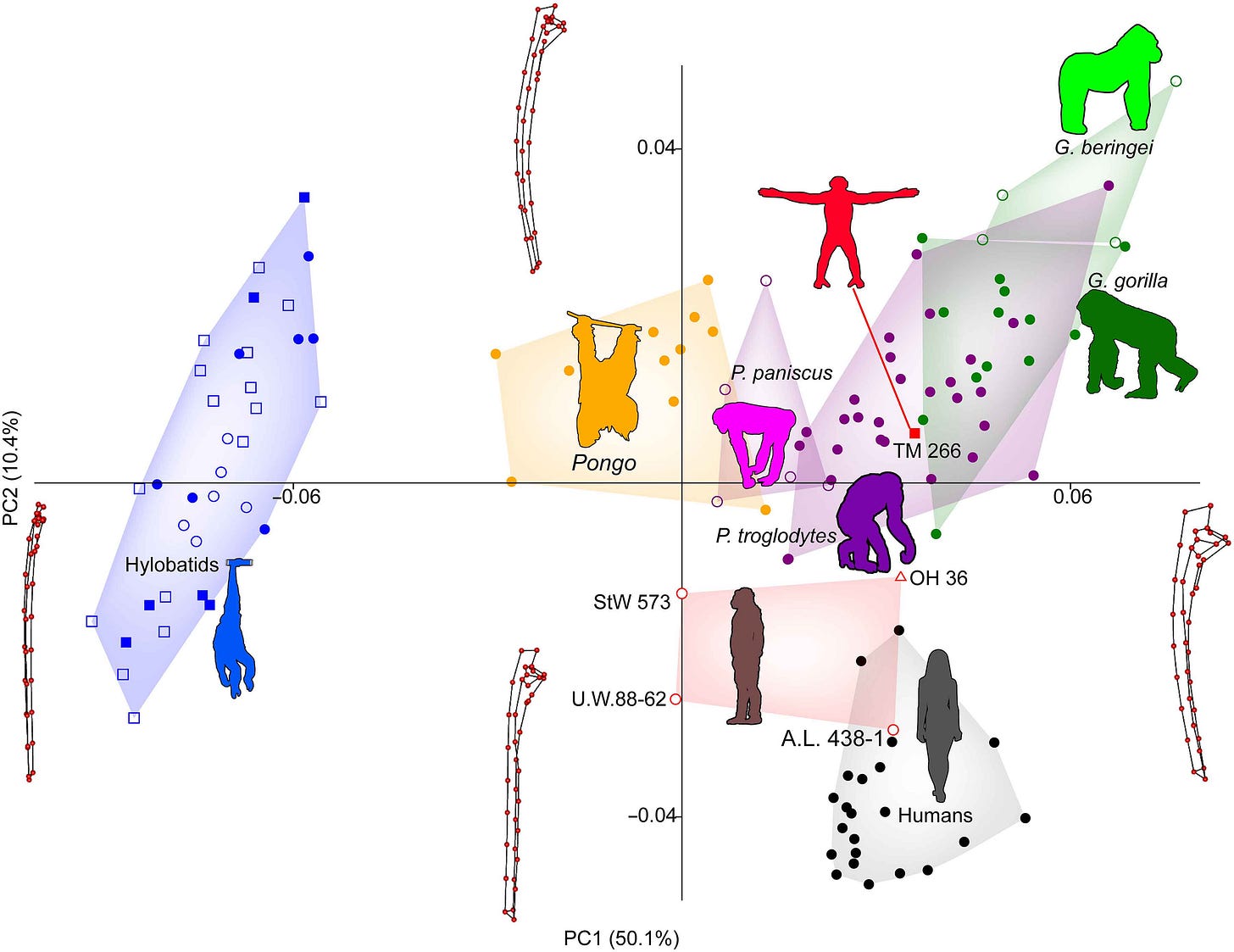

What I would say is that the S. tchadensis femoral form would work well in an Ardipithecus-like leg. It was not specialized in the same way as the femora of chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas; and that may simply mean that S. tchadensis was not a terrestrial quadruped as those living African apes are. Even so, Williams and coworkers find that the shape dimensions of the TM 266-01-063 femur fit between chimpanzees and gorillas when compared with other apes, hominins, and humans.

The ulnae

The S. tchadensis arm bones are a left ulna shaft, TM 266-01-050, and a right ulna partial shaft, TM 266-01-358. An obvious first question is whether any of these bones collected at the TM 266 locality come from the same individual—either as each other, the femur, the Toumaï skull and mandible, or all of the above. The proportion of length and joint diameters of the ulna compared to the femur shaft can be very informative about locomotion.

Details about the fossils’ context are scanty. The fossils were surface finds and, as told by Daver and coworkers, the TM 266 locality covered an estimated 1.5 square kilometers in 2001 when these fossils were collected. The only published photos from the field show fossils after being moved. The hominin teeth from the locality represent at least three different individuals.

Alain Beauvilain and Jean-Pierre Watté told the story of the collection of the Toumaï skull, including field photos showing the femur and skull. They suggested that the skull and other bones had been moved from their original contexts by desert peoples sometime before the scientific expedition found them. Whether that is the case or not, there is no evidence of anatomical association of the fossils at the time of discovery.

“Given the minimum number of three hominin individuals calculated for TM 266, suggestions that [the Toumaï skull] and any of the newly described postcranial elements belong to the same individual remain highly hypothetical.”—Guillaume Daver and coworkers

Probably for this reason, Daver and collaborators did not address the relative sizes or lengths of the ulnae and femur. Williams and coworkers observe that even though the ulnae may represent different individuals, they seem to come from individuals that are not very different in mass. With that in mind, they attempt a length comparison, finding that the more complete ulna isn’t long in the way that a chimpanzee or gorilla would be.

Furthermore, the coronoid notch that articulates with the humerus at the elbow joint faces forward. Knuckle-walking apes have this notch oriented a bit upward, helping with weight support across the elbow joint. Forward-facing ulnae are found in humans and Australopithecus, but also in orangutans and gibbons.

Otherwise, however, the ulnar shafts are a lot like chimpanzee and gorilla ulnae. They’re curved along their shaft. Marc Meyer and coworkers, including Williams, have observed that this aspect of the S. tchadensis ulnae is similar to knuckle-walkers, related to the demands of propulsion across the elbow joint. An analysis of ulna shape puts the S. tchadensis form right in the middle of the chimpanzee range of variation, far from any hominins. There’s little in this anatomy to suggest that upright posture had any influence upon the S. tchadensis upper limb.

Still, a handful of early hominin ulnae do share a chimpanzee-like level of curvature, especially two fairly complete ulnae attributed to Paranthropus boisei. With the recent description of the highly robust hand bones of P. boisei by Carrie Mongle and collaborators, it may be that the curved ulna is part of an adaptation for foraging on the ground, maybe uprooting tubers or digging. That might account for a similarity of form even with different locomotor demands.

Where my thoughts are trending

When Brunet and collaborators published their description of S. tchadensis in 2002, I was skeptical of the idea that this species was a member of the our branch of primates. In addition to the poor evidence for a pattern of upright posture or locomotion from the Sahelanthropus skull, there was something else shaping my thinking.

Mainstream interpretations of DNA evidence at the time suggested that the human-chimpanzee last common ancestor lived only around 5 million years ago. But the fossils of Sahelanthropus tchadensis at the time of their discovery were placed between 7 and 6 million years ago, which was later refined to a range between 7.2 and 6.8 million years. That range of ages was seemingly too old by 2 million years for this primate to be a member of the human branch.

A lot has changed in twenty years. New discoveries of Australopithecus have shown that these early hominins were not all alike in their pattern of movement. The skeleton of another relative, Ardipithecus ramidus, was first described in 2009. This species had its own distinctive anatomical pattern: Upright trunk, neck, and head posture combined with an ability to stand with extended hip, yet retaining long arms, fingers, and grasping feet for climbing.

Meanwhile, the genomic record has grown to encompass much larger samples of all living apes and humans. DNA now suggests that human ancestors may have started to diverge from chimpanzee and bonobo ancestors by the time of Toumaï, but with continued interbreeding for a long time.

“We see nothing of these slow changes in progress, until the hand of time has marked the long lapse of ages, and then so imperfect is our view into long-past geological ages, that we only see that the forms of life are now different from what they formerly were.”—Charles Darwin

The reason why we notice the differences between hominins after 4 million years ago and living great apes is the extinction of the intermediate forms. But in the period between 8 million and 5 million years ago, the genetic evidence suggests the ancestral populations were mixing with each other, occasionally exchanging DNA. Perhaps the early hominin lineage and early chimpanzee-bonobo lineage had different habitat preferences and subtly different locomotor strategies during this early period of differentiation. But they were not too different to mix and mate.

I tend to agree with Williams and coworkers’ new analysis. Sahelanthropus tchadensis may have walked and climbed in a similar way to Ardipithecus ramidus. This species is accepted as early hominins by many researchers, and S. tchadensis is not very different in the parts both preserve. If that’s the case, almost certainly early chimpanzee-bonobo ancestors had this general body form also. Maybe the most important question about S. tchadensis is not whether it was yet a biped, but whether its early chimpanzee-bonobo contemporaries were yet knuckle-walkers.

It is hard to write about comparisons of two groups without making it sound like a dichotomy between the two groups. But evolution defies dichotomies. Each species evolves from ancestors through a continuum of genetic, anatomical, and behavioral variation.

Our ancestry is no different. Was S. tchadensis a hominin? To really answer that, we’ll need much more information about the many extinct populations that existed as part of this network of early apes.

Notes: I highly recommend reading the Guardian article by Scott Sayare, “The curse of Toumaï: an ancient skull, a disputed femur and a bitter feud over humanity’s origins”. The piece includes perspectives from many scientists who were involved in study of the Sahelanthropus remains. Even though I’ve followed this story for years, I learned a lot from Sayare’s account that I had not previously known.

What the opposing teams have written about the fossils has helped me learn a lot. This post would not have been possible without Scott Williams and colleagues’ paper that provides clear illustrations. Still, without open access to the data from these fossils, it has been hard for me to judge what any of the researchers may not have noticed. I’d love to see these become available for anyone to inspect and print for their own research and teaching.

References

Beauvilain, A., & Watté, J.-P. (2009). Was Toumaï (Sahelanthropus tchadensis) buried? Anthropologie, 47(1/2), 1–6.

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Lieberman, D. E., Likius, A., Mackaye, H. T., Ponce de León, M. S., Zollikofer, C. P. E., & Vignaud, P. (2005). New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad. Nature, 434(7034), Article 7034. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03392

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Mackaye, H. T., Likius, A., Ahounta, D., Beauvilain, A., Blondel, C., Bocherens, H., Boisserie, J.-R., De Bonis, L., Coppens, Y., Dejax, J., Denys, C., Duringer, P., Eisenmann, V., Fanone, G., Fronty, P., Geraads, D., … Zollikofer, C. (2002). A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature, 418(6894), Article 6894. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00879

Cazenave, M., Pina, M., Hammond, A. S., Böhme, M., Begun, D. R., Spassov, N., Gazabón, A. V., Zanolli, C., Bergeret-Medina, A., Marchi, D., Macchiarelli, R., & Wood, B. (2025). Postcranial evidence does not support habitual bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis: A reply to Daver et al. (2022). Journal of Human Evolution, 198, 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103557

Daver, G., Guy, F., Mackaye, H. T., Likius, A., Boisserie, J.-R., Moussa, A., Pallas, L., Vignaud, P., & Clarisse, N. D. (2022). Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad. Nature, 609(7925), Article 7925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04901-z

Lebatard, A.-E., Bourlès, D. L., Duringer, P., Jolivet, M., Braucher, R., Carcaillet, J., Schuster, M., Arnaud, N., Monié, P., Lihoreau, F., Likius, A., Mackaye, H. T., Vignaud, P., & Brunet, M. (2008). Cosmogenic nuclide dating of Sahelanthropus tchadensis and Australopithecus bahrelghazali: Mio-Pliocene hominids from Chad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(9), 3226–3231. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708015105

Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Spurlock, L., Asfaw, B., & White, T. D. (2009). The Pelvis and Femur of Ardipithecus ramidus: The Emergence of Upright Walking. Science, 326(5949), 71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175831

Macchiarelli, R., Bergeret-Medina, A., Marchi, D., & Wood, B. (2020). Nature and relationships of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Journal of Human Evolution, 149, 102898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102898

Meyer, M. R., Jung, J. P., Spear, J. K., Araiza, I. Fx., Galway-Witham, J., & Williams, S. A. (2023). Knuckle-walking in Sahelanthropus? Locomotor inferences from the ulnae of fossil hominins and other hominoids. Journal of Human Evolution, 179, 103355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103355

Mongle, C. S., Orr, C. M., Tocheri, M. W., Prang, T. C., Grine, F. E., Feibel, C., Patel, B. A., Laureijs, O., Hobbs, T. E., Maiolino, S., Rossie, J., Mbogo, W., Du Plessis, A., Lonyericho, J., Woto Huka, W., Sale, H., Umuro, A., Yirgudo, P., Dalacha, I., … Leakey, L. N. (2025). New fossils reveal the hand of Paranthropus boisei. Nature, 647(8091), 944–951. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09594-8

Sayare, S. (2025, May 27). The curse of Toumaï: An ancient skull, a disputed femur and a bitter feud over humanity’s origins. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2025/may/27/the-curse-of-toumai-ancient-skull-disputed-femur-feud-humanity-origins

Williams, S. A., Wang, X., Araiza, I., Guerra, J. S., Meyer, M. R., & Spear, J. K. (2026). Earliest evidence of hominin bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Science Advances, 12(1), eadv0130. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv0130

Wolpoff, M. H., Hawks, J., Senut, B., Pickford, M., & Ahern, J. (2006). An Ape or the Ape: Is the Toumaï Cranium TM 266 a Hominid? PaleoAnthropology, 2006, 36–50.

Wolpoff, M. H., Senut, B., Pickford, M., & Hawks, J. (2002). Sahelanthropus or “Sahelpithecus”? Nature, 419(6907), 581–582. https://doi.org/10.1038/419581a

Zollikofer, C. P. E., Ponce De León, M. S., Lieberman, D. E., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Likius, A., Mackaye, H. T., Vignaud, P., & Brunet, M. (2005). Virtual cranial reconstruction of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Nature, 434(7034), 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03397