Human origins science in 1925: the good, the bad, and the fake

As I look back at a sometimes-confusing picture of a science in its early days, I see some connections with today's landscape.

As I mentioned last month, I’ll be participating next week in the events marking the centennial of the Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee. The 1925 “trial of the century” featured a real showdown: a final cross-examination of William Jennings Bryan by counsel for the defense Clarence Darrow, all on a makeshift stage erected outdoors in the courthouse square.

The biggest showdown it was. But not the first.

Bryan spent years on the lecture circuit expounding his views on religion, social matters, and especially the case against evolutionary science. Interviews and newspaper articles, and the book-length compilation of his lectures titled In His Image disseminated those ideas widely.

Some public-oriented scientists of the day rose to oppose these arguments—most notably the paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, head of the American Museum of Natural History. The years-long lead-up of written exchanges, with Osborn and other scientists taking on a three-time Presidential candidate, helped stoke the sensational public interest in the Scopes Trial.

“Today the earth speaks with resonance and clearness and every ear in every civilized country of the world is attuned to its wonderful message of the creative evolution of man, except the ear of William Jennings Bryan; he alone remains stone-deaf, he alone by his own resounding voice drowns the eternal speech of nature.”—Henry Fairfield Osborn

Today in the light of the intervening century of scientific progress, those public exchanges look different. Defenders of evolution like Osborn had some strong evidence on their side that has stood the test of time. Yet at the same time they leaned into some ideas that were misleading, wrong, or even fraudulent.

Those bad ideas did not stop some great science from happening, but they had effects both scientific and social. As I look at them today, I see how much they resemble some of today’s scientific environment.

The good

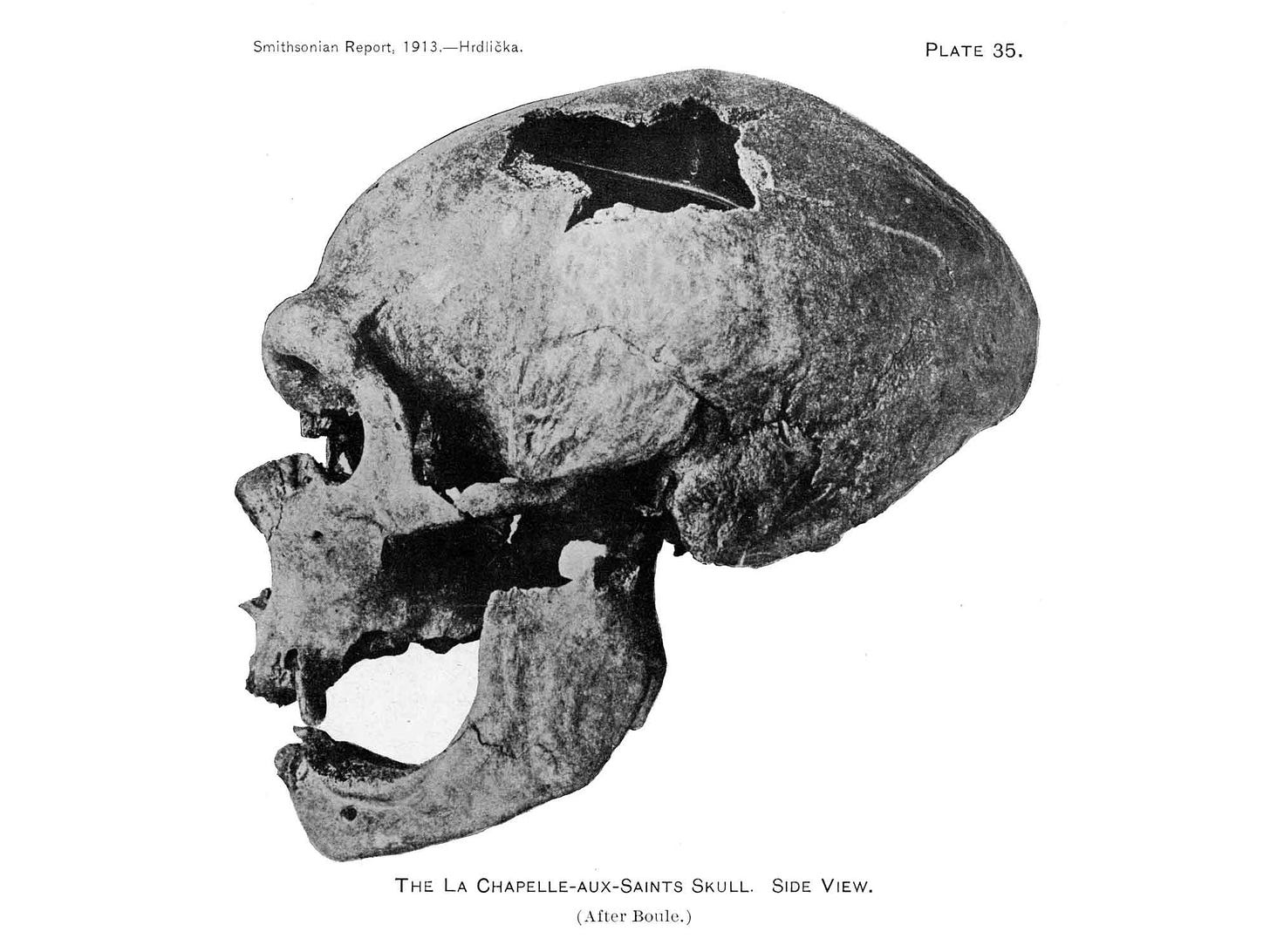

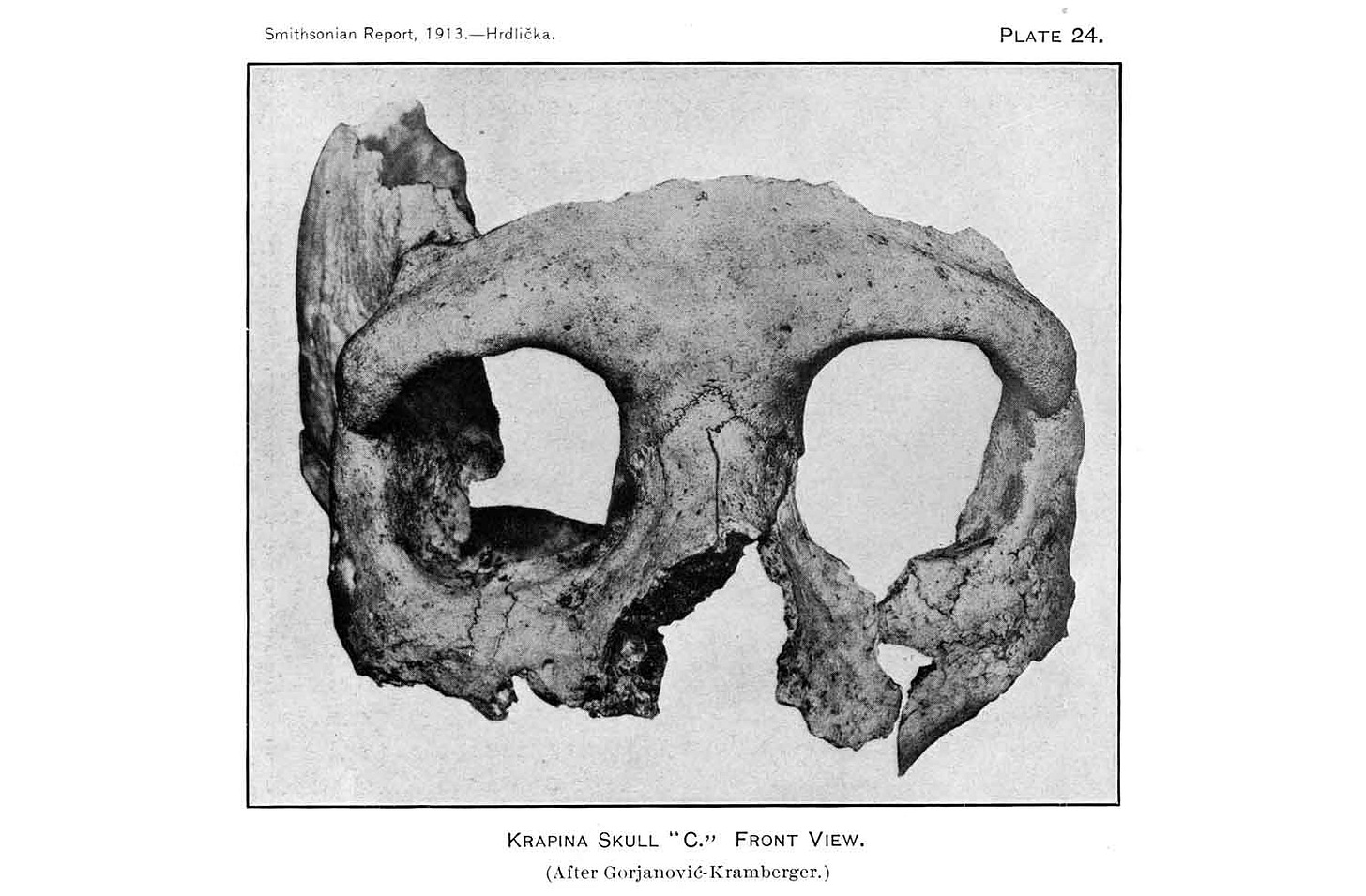

The Neanderthals. First recognized as a distinct ancient group in 1856, by 1925 archaeologists had uncovered ancient skeletons and bones of this population from France, Italy, Croatia (then part of Yugoslavia), Gibraltar, Belgium, and Germany. Repeated discoveries had confirmed that this group existed during the Pleistocene together with extinct animals like mammoths, and that their stone tool cultures were different from those of later groups.

In the intervening years, scientists have discovered many more Neanderthals. We’ve developed a much better understanding of their chronology, widened their geographic range, and shown the genetic connections between some of their groups and living people. We’ve also come a long way toward overcoming stereotypes of the Neanderthals that were widely held by scientists back in 1925. The “grisly folk” evoked by the writer H. G. Wells have given way to a richer and more nuanced understanding of their cultures.

The Taung Child. The tiny skull and natural endocast described by the anatomist Raymond Dart were the first fossil evidence that the human family had arisen in Africa. Dart’s interpretation of the teeth and the base of the natural endocast suggested a human relative with an upright posture and small canines, but with an ape-sized brain and face. In these details he got it right.

The skull’s description in early 1925 was perfect timing for the Scopes Trial. Still, Dart’s discovery was not universally accepted at the time—some of the loudest voices of the British anatomical establishment raised early doubts about the skull’s relationship to humans, and many others took a cautious wait-and-see attitude.

Pithecanthropus erectus. The first of fossils of this species were recovered from an ancient river terrace near Trinil, Java, under the direction of Eugene Dubois in 1891. The skull had a protruding brow, and showed a brain smaller than most humans but larger than any other living primate. There was also a long thighbone, unearthed in 1892, bearing all the hallmarks of bipedal walking.

Our knowledge of the place of the Pithecanthropus fossils is much clearer today than in 1925. Today most scientists understand this fossil species—now generally known as Homo erectus—to be one of the most numerous, long-lasting, and geographically widespread human relatives. Still, some of the early picture was misleading. Dubois imagined that the femur and skull might have come from a single individual; today most experts accept that the 1892 femur probably comes from a much later human relative. Other femora discovered later at Trinil confirmed that H. erectus did indeed walk and run in a human way.

Chronology. By 1925, geologists and archaeologists had developed clear methods for understanding the times that ancient fossils and artifacts represent. Of the periods when ancient humans and our relatives might have existed, paleontologists recognized Pleistocene, Pliocene, and Miocene on the basis of extinct animals that once lived. Within Europe, an idea of the succession of Ice Ages was becoming more and more solid. And the Stone Age archaeological record was categorized into three main phases: the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic, with some archaeologists beginning to recognize further divisions in the Paleolithic corresponding to the most ancient types of stone artifacts.

Still, there was one great weakness of chronology in this era. Putting fossils or geological strata into order from oldest to youngest was not a problem, as long as scientists kept the context straight. But geological principles gave rise to a relative chronology, not an absolute one.

Putting a calendar date on a fossil—say, 1.3 million years old—would have to wait for developments in physics from the 1940s and thereafter, especially the discovery and characterization of natural radioactive isotopes.

The bad

Human racial typology. The study of human evolution during the 1920s was considered to be a study of origins of human races. By itself, the interest in human variation and the evolution of various groups around the world was not bad. Anthropologists today still research these topics actively using modern methods. But in the 1920s mainstream thinking came from a widespread perception that human races are very different from each other. This gave rise to scientific errors with damaging social and political effects.

On the scientific side, anthropologists mostly assumed that races are distinct and must have originated very deep in the ancient past. Some even imagined that human races had evolved by the Pliocene or earlier. Mostly by the 1920s scientists had abandoned the incorrect notions that human groups should be recognized as different species, or had evolved from different ancestral primates. Even so, scientists of the era formulated more and more elaborate racial typologies. Some of them distinguished dozens of different human races, arranged in a hierarchy of superiority.

These ideas provided a veneer of intellectual backing for Jim Crow laws and other political, economic, and social manifestations of racism in the U.S. Bad scientific ideas about human races were not the only causes of racism, but the notion that races had immutable and ancient differences helped paper over the social injustices that maintained systems of discrimination.

Eugenics. Many evolutionary biologists of the 1920s were part of a movement to make evolution into an applied science of human racial improvement, called eugenics. They had a range of different aims for this project. Some wanted to reduce the toll of genetic disease and disability. Others imagined that selective breeding might steer the future evolution of humanity. Many scientists favored policies to implement eugenics principles by limiting immigration, an example being the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which restricted immigration from Asia. States in this era—following advice from some of the most well-known geneticists and physicians—passed laws requiring compulsory sterilization of people with certain mental or physical conditions.

Eugenics fed upon stereotypes of social class and race, and thereby appealed to a broad swath of progressive political leaders and social thinkers. The American Eugenics Society was cofounded by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1922 and included both academic and government elements.

Although the push for more eugenics laws lost steam after the Second World War, some sterilization laws were not overturned or repealed until the 1980s. Eugenics ideas remained part of mainstream human genetics into the 1960s.

The fake

Boskops. In 1913, workers excavating a drainage ditch near Boskop, south of Bloemfontein, found part of a skull. F. W. FitzSimons, supported by the naturalist Louis Péringuey at the South African Museum, became convinced that the Boskop fragments represented an extinct race that was a southern African equivalent of the Cro-Magnons of Europe, emphasizing what they saw as a large brain size. Into the 1920s, South African researchers including Raymond Dart identified several skulls from other sites as members of this purported race, the “Boskops”.

As the archaeological record of southern Africa developed, it became clear that these skeletal remains date to the last 10,000 to 20,000 years and are ancestors and close relatives of the historic peoples of this region. But even as the scientific idea died, the Boskops survived as myth—one of the last holdouts of an early twentieth-century notion that so-called “modern” races had existed alongside Neanderthals in Europe and other fossil groups in the tropics.

Hesperopithecus. Osborn himself in defense of human evolution pointed to a fossil tooth from Nebraska, found by the rancher Harold Cook. In Osborn’s mind the tooth was the earliest-known human relative, one that he had named Hesperopithecus haroldcookii. The evidence for the claim was very slim, although in 1922 it was published in Science, the leading scientific journal of the United States. The press dubbed the fossil “Nebraska Man”.

More digging at the site of the discovery in the 1920s yielded more complete fossils, making it clear that the worn tooth belonged to an ancient peccary, a North American pig relative. The article naming Hesperopithecus as a primate was retracted in 1927. The fossil was not fraudulent, but it is a shining example of scientists stumbling by extrapolating from incomplete evidence.

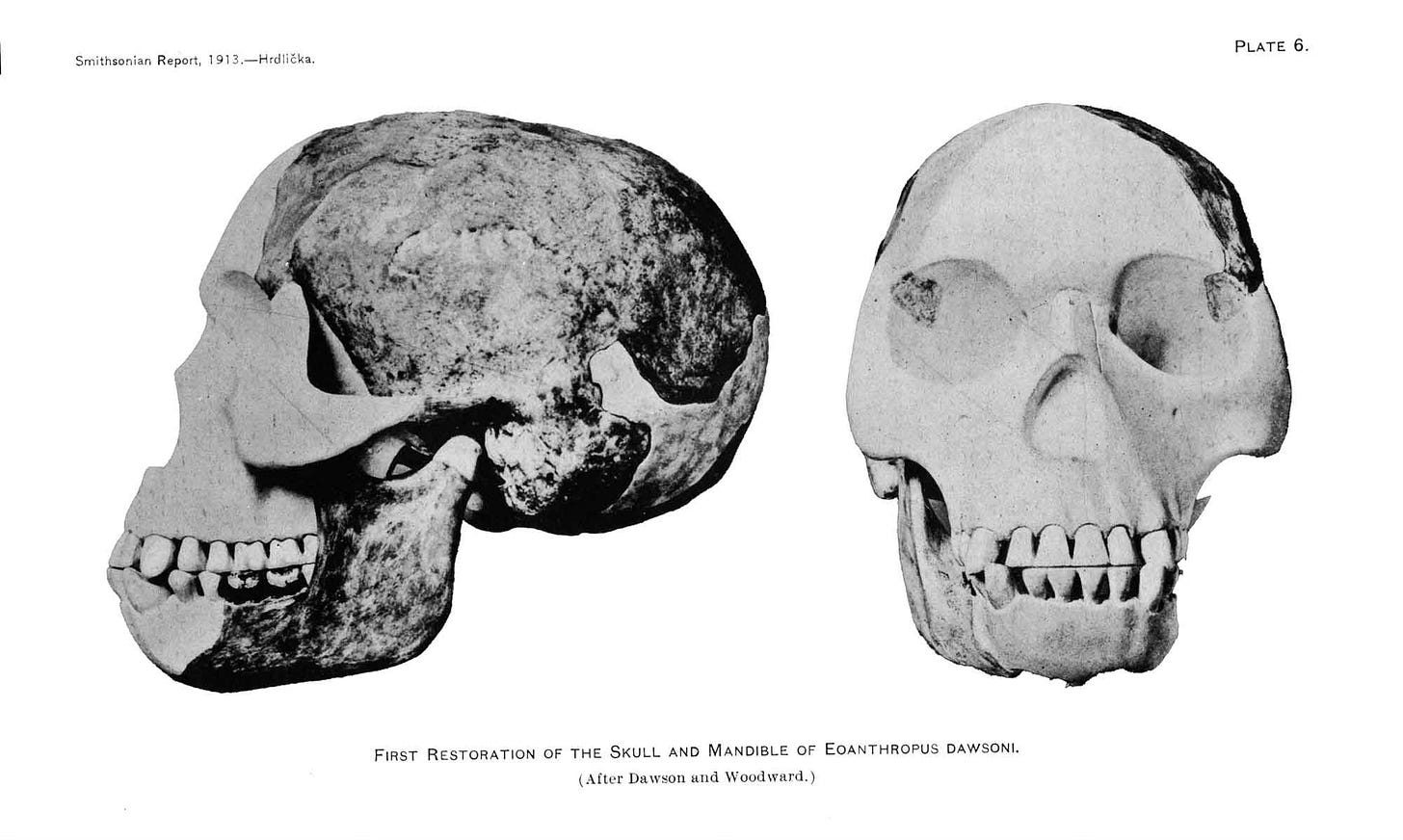

Piltdown. Some of the greatest minds of evolutionary science were suckered by an outright fraud, the so-called “Piltdown Man”, produced from an English gravel pit by amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson starting in 1912. At first Dawson found just pieces of a fragmented skull. Later he returned to the site with the anatomist Arthur Smith Woodward, finding a fragment of jaw and other pieces. A blue-ribbon committee including the anatomist Arthur Keith authenticated the finds, naming them Eoanthropus dawsoni and recognizing the species as a human relative of Pliocene age. The large human-sized brain combined with a very apelike jaw conformed to the widely-held notion that brainpower set humans on their evolutionary career.

It was all a hoax.

The traditional story of the hoax’s exposure focused on scientific methodology: The development of fluorine testing and later radiocarbon dating proved after three decades that the bones were not ancient.

But that story evades the series of serious blunders made by Keith, Woodward, and other Piltdown pushers. As Isabelle De Groote and coworkers showed in a 2016 analysis, the forger left obvious filing marks on the teeth, used dental putty and stains, and a purported artifact from Piltdown had been carved with a steel knife. All these aspects could have been noticed in any analysis of the bones.

The real story of Piltdown is one of scientific preconceptions and gullibility. De Groote and coauthors supported the view was that Dawson was the lone forger, who knew what scientists were expecting in a “missing link”. Even so, many scientists of the time doubted the Piltdown specimens or rejected the interpretation offered of them.

Bottom line

Looking back at the 1920s, this era unquestionably offered a weird landscape of ideas about how humans evolved. As I look toward reviewing today’s science, I’m so happy at the extremely strong foundations of data across disciplines we can draw upon in our work.

Yet this look at the past offers some lessons that resonate in today’s world.

Every one of the bad and fake ideas had vocal scientific detractors. On race, there were scientists at the time, such as the anthropologist Frans Boas, who noted that biological differences between races were much less than they might seem. The eugenics movement had been started in part by prominent geneticists, but by the 1920s some recognized the movement’s excesses. Thomas Hunt Morgan and Raymond Pearl both turned into vocal critics of many aspects of the eugenics movement after helping pave the way toward eugenics in their earlier careers.

Piltdown met the opposition of some very prominent anthropologists and paleontologists. Franz Weidenreich, Marcellin Boule, and Gerrit Smith Miller all came fast to the correct interpretation that the skull and jaw represent different animals: the skull human, the jaw ape. Of course without direct examination of the bones, they could not guess that what they correctly saw as a jumble was also an intentional hoax.

Even in cases without deliberate fraud, like Pithecanthropus, associating different specimens within any ancient context was a well-known challenge. This has remained a problem with some recent discoveries, illustrated by the case of the Homo floresiensis remains and archaeological finds from Liang Bua.

Wider access to original data from early finds would have led to a more accurate understanding of the evidence in these cases. Hesperopithecus is a case in point: The fossil was ambiguous, and wider investigation of the site quickly resolved its identity. Today the most solid results come from sites where data are made available openly and rapidly. That lesson is still taking hold, and too many researchers still conceal or withhold data from their research, sometimes for years.

The enduring discoveries of fossil human relatives that were shaking the scientific ground at the time, including the famous “Taung child”, Australopithecus africanus, were subject to misrepresentation by rival scientists. The heat was elevated by incorrect beliefs about human races and their origins. The sidelining of Neanderthals, for example, started from the assumption that today’s human races already existed long before the fossil Neanderthals had lived.

Indeed, the biggest lesson that the 1920s have to teach us today may be the power that “mainstream” science had to shape conversation about these discoveries. Just as today, the journals Nature and Science published sometimes-credulous accounts of new fossils, disseminating them to the broadest readership of scientists. Some would turn out to be mere flashes in the pan, others gave rise to decades of debate before falling. A few proved to have enduring importance.

Each published debate—which together form our record of the era—was selected by editors who sought and valued the views of Keith, Osborn, and other select authorities. These experts sometimes had feet of clay. That’s no surprise, all of us do. Still, looking back I can’t help but feel a missed opportunity to bring out better conversation, more focused on the evidence and big issues, which might have opened new pathways of scientific discovery.

References

Dart, R. A. (1923). Boskop Remains from the South-east African Coast. Nature, 112(2817), 623–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/112623a0

Dart, R. A. (1925). Australopithecus africanus The Man-Ape of South Africa. Nature, 115(2884), Article 2884. https://doi.org/10.1038/115195a0

De Groote, I., Flink, L. G., Abbas, R., Bello, S. M., Burgia, L., Buck, L. T., Dean, C., Freyne, A., Higham, T., Jones, C. G., Kruszynski, R., Lister, A., Parfitt, S. A., Skinner, M. M., Shindler, K., & Stringer, C. B. (2016). New genetic and morphological evidence suggests a single hoaxer created ‘Piltdown man.’ Royal Society Open Science, 3(8), 160328. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160328

Fitzsimons, F. W. (1915). Palæolithic Man in South Africa. Nature, 95(2388), 615–616. https://doi.org/10.1038/095615c0

Gregory, W. K. (1927). Hesperopithecus Apparently Not an Ape Nor a Man. Science, 66(1720), 579–581. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.66.1720.579

Hrdlička, A. (1915). The Most Ancient Skeletal Remains of Man. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Keith, S. A. (1915). The Antiquity of Man. Williams and Norgate.

Keith, Arthur, Elliot Smith, Grafton, Woodward, Arthur Smith, & Duckworth, W. L. H. (1925). The Fossil Anthropoid Ape from Taungs. Nature, 115(2885), 234–236. https://doi.org/10.1038/115234a0

Osborn, H. F. (1922). Hesperopithecus, the First Anthropoid Primate Found in America. Science, 55(1427), 463–465. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.55.1427.463