More hominins raised from beneath the waves

Fossils from the Madura Strait of Indonesia remind us of the expansive sunken landscapes of our ancestors.

Many ancient landscapes are drowned today beneath the sea. For most of the last million years a large volume of Earth’s water was locked up in great ice sheets across North America, Asia, and Europe. As a result, the seas ranged as low as 120 meters or more below their present level.

Ancient humans and other animals ranged across the exposed areas of the continental shelf. These are the areas that once connected islands to continents, that flanked the ancient mouths of rivers and ancient shorelines. Archaeologists know that these were some of the most productive homelands for our ancestors. Their secrets lie locked beneath the waves.

Land reclamation operations sometimes reveal undersea fossils and stone tools as they dredge vast volumes of sand and gravel from the sea bottom, dumping it in the shallows to create new land. Two fossil human relatives have been found in such operations: one from the sea off the Netherlands, one from the Taiwan Strait.

Two new cases have just been reported from Indonesia. They come from the bottom of the Madura Strait, the narrow water passage on the northeast coast of Java separting it from the smaller island of Madura.

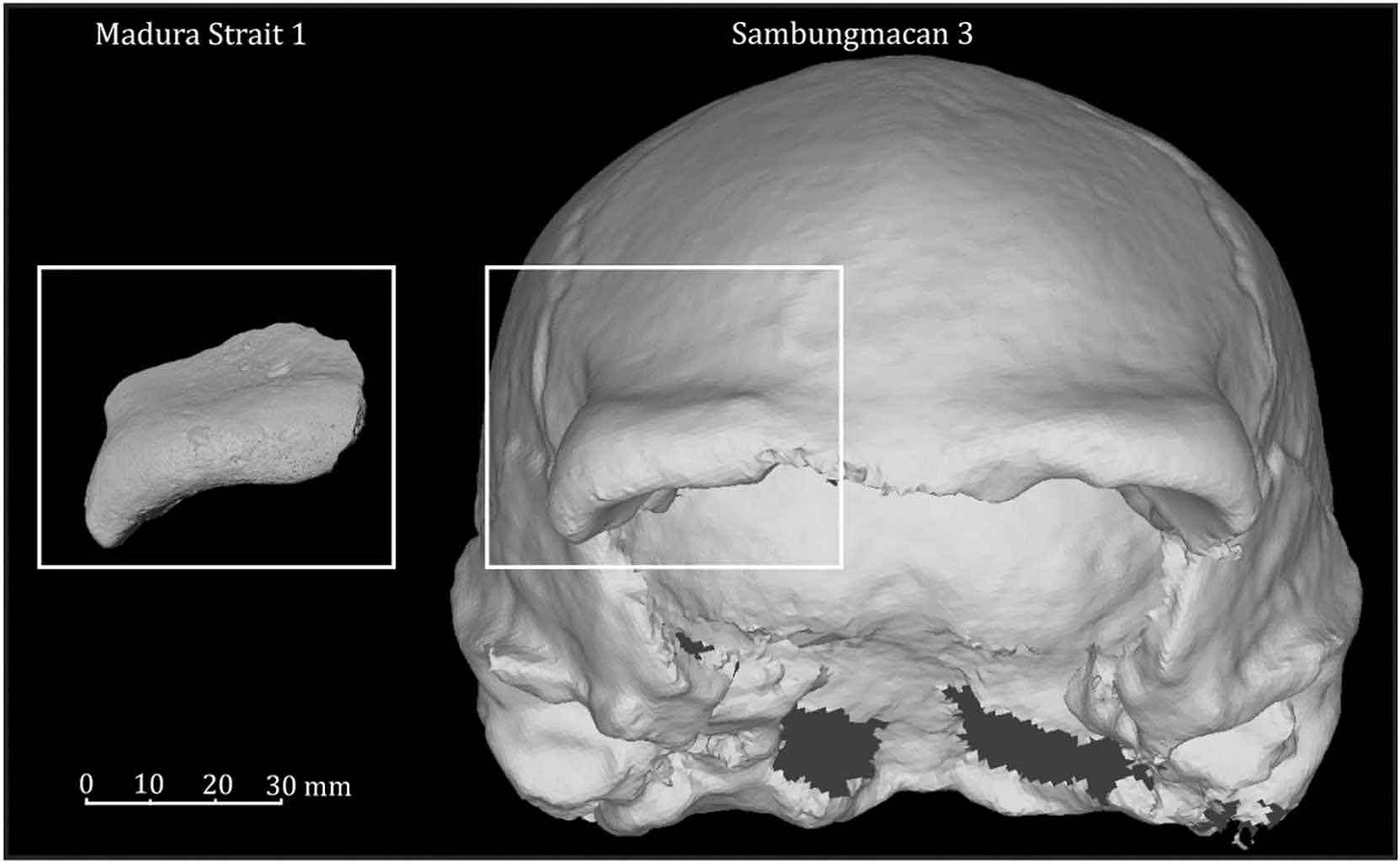

Over the past decade, Harold Berghuis has surveyed a tract of reclaimed land off the Gresik coastline north of Surabaya, combing it for fossils. In a new series of papers, he and his collaborators report on more than 1200 fossils of many species, out of more than 6700 that Berghuis collected. Two of these belong to hominins. One is a piece of frontal bone, the other a small piece of parietal bone, both from Homo erectus-like individuals.

“The more than 100 ha wide reclamation area was meticulously searched on hands and knees [by Berghuis], collecting vertebrate remains visible to the naked eye”—Harold Berghuis and coworkers

I’m impressed at the scope of detective work that Berghuis and his team have put into these new fossils. In four new articles in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans they report dozens of small clues about these ancient people and their behavior, including some animal bones with fractures and cutmarks that may have been their prey.

The site of the dredging off the port of Surabaya was close to 20 km from the reclaimed land. By putting together core samples from the bed of the Strait, nearby cores from the construction of a bridge, records of the dredging operation, and geological samples from the reclaimed land, the team were able to piece together the geological situation of the fossils. From a few chunks of intact sediment, the team obtained sand grains that could be assessed using OSL (optically stimulated luminescence) testing, with age estimates of 162 ± 31 and 119 ± 27 ka. They reconstruct the sea bottom source as a sedimentary deposit of the Solo River roughly during the time between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago.

The fossil skull fragments are very similar to other skulls and skull fragments from Java that date to this time. The large collection of skulls from Ngandong, Java, dating to between 140,000 and 90,000 years ago have browridges that resemble the small piece from the Madura Strait. Berghuis and coworkers found that the closest comparison is a skull known as Sambungmacan 3, a skull with its own fascinating history—first brought to science from a collectors’ shop in Manhattan.

The two new fossils can say only a small amount about the shape of these particular individuals or the populations of which they are part. They were sucked from sediments across a thickness of many meters and a distance of kilometers. They are best seen as a hint that the few sites higher on Java with similar fossils are the tip of an iceberg of ancient people across the broader Sunda Shelf.

Berghuis collected a wide range of fossil animal bones. Many are extinct species, including some that were not present in the very extensive faunal collection from Ngandong. These hint at differences in ecology between the coastal lowland plain and the somewhat higher Solo valley. A very small number of the animal bones have linear marks that Berghuis and collaborators think were likely made by hominins. No stone tools are reported from the reclaimed land.

Just last week I wrote about the Penghu 1 fossil jaw, dredged from the bottom of the Taiwan Strait. The peptide fragments of proteins in this jaw align it with the Denisova 3 individual and Xiahe 1 mandible, three fossils across some 4000 kilometers that belong to a larger “Denisovan” population.

The Madura Strait fossils come from roughly the same range of time, from a region where modern people upon their arrival mixed with a Denisova-like lineage. This raises the question: Are these fossils those of Denisovans?

I have for some time thought it likely that the Ngandong, Sambungmacan, and other later Middle Pleistocene fossils from this region are part of a Denisova-like lineage. Other scientists tend to call these samples Homo erectus. They’re focusing on shared characteristics of the skull between these fossils and much earlier fossils from nearby, including those from Sangiran and Trinil. This line of thinking tends to accentuate the shared geographic position of all these fossils on the island of Java.

But the later fossils are different from the earlier ones in many ways, too. For me, the Madura Strait discovery is another reminder that the island-ness of Java is a temporary and short-term phenomenon. For most of the Pleistocene, there were vastly more hominins on the low-lying reaches of the exposed Sunda Shelf than on Java. Borneo and Sumatra, too, are so much larger than Java, but have not provided the same sedimentary fossil exposures. Biomolecules like protein from bone and teeth may help form an answer to whether these fossils were Denisova-like, or whether the vast Sunda Shelf was a refuge for Homo erectus while Denisovans diversified elsewhere.

We are only beginning to understand how the biogeography of this region mattered to hominins. Across this vast sunken landscape people were thrust together, and sometimes separated for thousands of years. They traversed deepwater straits on several occasions—leading to occupation of the Philippines, Flores, and Sulawesi.

So far scientists have done so little to understand the ecology and lifeways of hominin populations of the submerged coastal shelves. It’s a great area for more research.

Notes: My article on the Penghu 1 mandible focused on the bias in sex of fossils from the small Denisovan sample: “The problem when all the fossils are male”.

All the articles below describing the science of the Madura Strait finds are open access. I congratulate the authors on making these available to everyone and enabling reuse of their images and data.

References

Bello, S. M., & Stringer, C. B. (2025). The newly uncovered Madura Strait fossil assemblage and its role in Pleistocene hominin dispersals in Southeast Asia. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2025.100070

Berghuis, H. W. K., Kaifu, Y., Wibowo, U. P., van Kolfschoten, T., Sutisna, I., Noerwidi, S., Adhityatama, S., van den Bergh, G., Pop, E., Suriyanto, R. A., Veldkamp, A., Joordens, J. C. A., & Kurniawan, I. (2025). The late Middle Pleistocene Homo erectus of the Madura Strait, first hominin fossils from submerged Sundaland. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2025.100068

Berghuis, H. W. K., van den Bergh, G., van Kolfschoten, T., Wibowo, U. P., Kurniawan, I., Adhityatama, S., Sutisna, I., Verheijen, I., Pop, E., Veldkamp, A., & Joordens, J. C. A. (2025). First vertebrate faunal record from submerged Sundaland: The late Middle Pleistocene, hominin-bearing fauna of the Madura Strait. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2024.100047

Berghuis, H. W. K., van Kolfschoten, T., Wibowo, U. P., Kurniawan, I., Adhityatama, S., Sutisna, I., Pop, E., Veldkamp, A., & Joordens, J. C. A. (2025). The taphonomy of the Madura Strait fossil assemblage, a record of selective hunting and marrow processing by late Middle Pleistocene Sundaland hominins. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 100055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2024.100055

Berghuis, H. W. K., Veldkamp, A., Adhityatama, S., Reimann, T., Versendaal, A., Kurniawan, I., Pop, E., van Kolfschoten, T., & Joordens, J. C. A. (2025). A late Middle Pleistocene lowstand valley of the Solo River on the Madura Strait seabed, geology and age of the first hominin locality of submerged Sundaland. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2024.100042