The ancient Egyptian legacy of anatomical science

The early foundations of human anatomy were built from traditions of medicine, embalming, and animal sacrifice.

Anatomical knowledge is central to biology. Its subjects are tissues, organs, and bodies, their structure and functions. While the idea of Darwinian evolution is less than 200 years old, the study of anatomy has vastly older foundations, spanning cultures across thousands of years.

One of the things I love to share in my classes is the way that anatomical science emerged across history. It ties together diverse peoples and periods of history in ways that no other science does. Anatomy got its start from practical knowledge that was constantly renewed by everyday experience. Traditions of practical knowledge from activities like butchery were transformed at times and places into specialized and systematic training. Some of these traditions we might describe as scientific, others were clearly mystical.

No ancient society illustrates this better than Egypt during the time of the Pharoahs. Anatomy in Egypt was part of a system of knowledge, sustained within skilled professions like medicine, surgery, and embalming. Each had its own specialists and traditions passed from teachers across millennia.

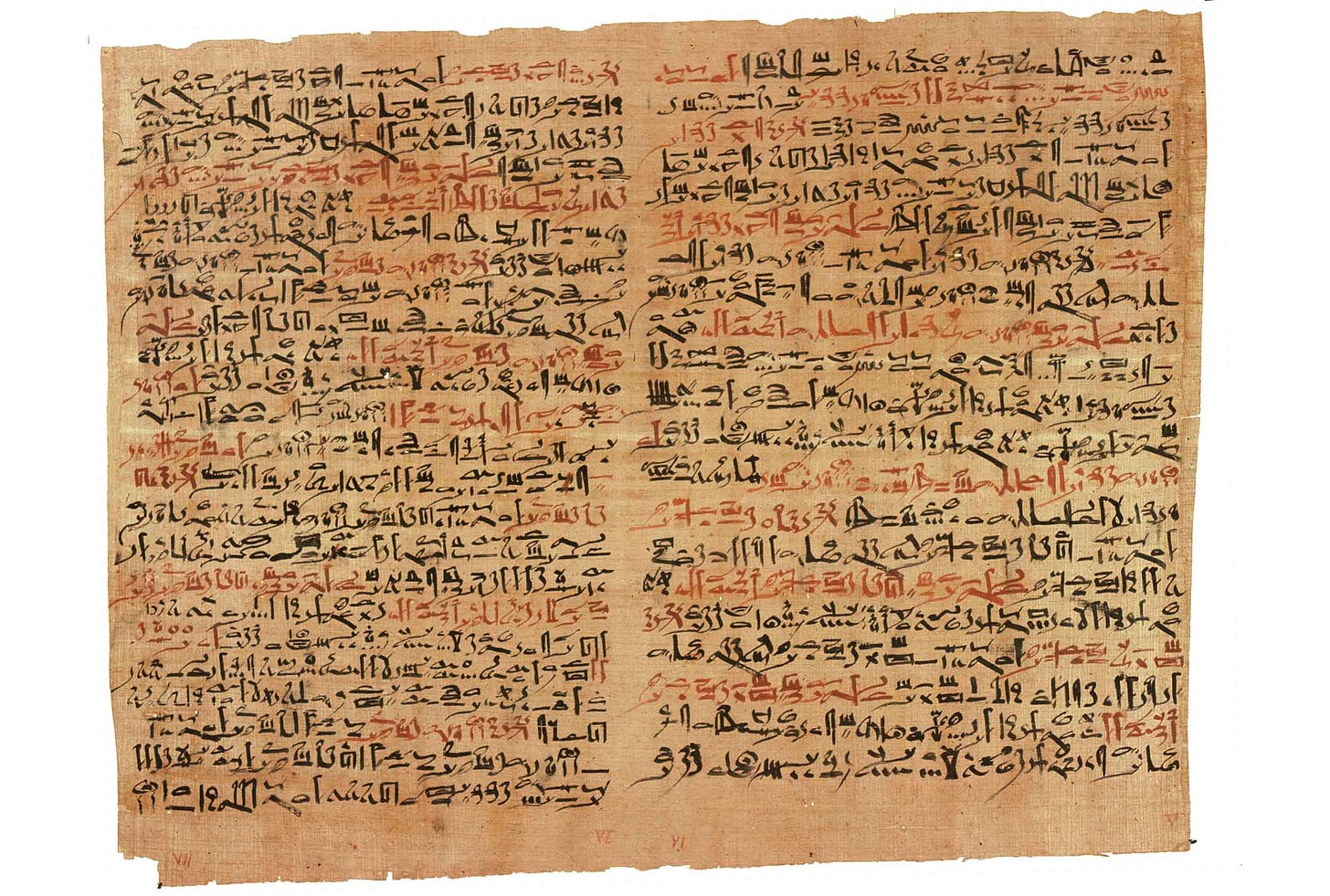

Medical papyri

Early anatomical records that have survived come from the time of the late Middle Kingdom and early New Kingdom, between 1800 BCE and 1200 BCE.

For example, the Ebers Papyrus—so-named because it was purchased by the Egyptologist Georg Ebers in 1873—is a 20-meter-long scroll consisting of more than 100 pages of medical information. The papyrus describes herbal remedies, magical incantations, and includes a section describing the network of blood vessels with the heart at its center.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is another long text that is devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of trauma. It details 48 case studies of traumatic injuries, organized from head to torso, providing guidance for examination, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatments. These case studies are organized with scripts for the practitioner to read to the patient, ranging from the hopeful, “This is a medical condition I can treat”, the challenging, “This is a medical condition with which I can contend”, or the ominous, “This is a medical condition I cannot treat.”

“Then you are to say about him: ‘One suffering from an oozing gash/cutting wound in his head, penetrating to the bone, and perforating the membranous lining of his cranium. The ligaments (cords) of his jaw are contracted, while he bleeds from his nostrils and his ears, and he suffers stiffness in his neck. [This is] a medical condition with which I can contend’.”—Edwin Smith Papyrus, translation in Sanchez and Burridge, 2007

This papyrus is remarkable for its observations of the influence of brain and spinal cord injuries on the body, including paralysis from some injuries, and weakness of the contralateral side of the body. It has descriptions of cranial sutures, and the diagnostic advice refers to the external surface of the brain and intracranial pulsations. The papyrus also mentions other organs, from heart and liver to kidneys, spleen, and bladder.

Sustaining traditions

Few documents have survived from this period more than 3500 years ago. Most are mere fragments. Without the preservation of such exceptional examples, we might only guess at the Egyptian practices and knowledge in this area.

What I keep in mind is that a document like the Edwin Smith Papyrus could not exist in isolation. Ever since the 1920s when it was first translated, scholars have considered it to be a copy of a much older text. The scroll dates to around 1600 BCE but includes signs that were in more frequent use in Old Kingdom times, up to 3000 BCE. A scroll like this would have been part of a working library, kept in a temple or individual practitioner’s chest of books. Other papyri and older inscriptions give indications that books of medical knowledge were kept together and consulted when difficult cases arose. Scribes meticulously copied these documents, word for word, enabling them to be passed widely across Egypt.

The training of physicians was varied. Many were trained within families or by apprenticeships. Some temple institutions offered a more formal training. In particular, the institution known as the “House of Life” (Per Ânkh) is mentioned in histories as a place that supported the practice of medicine and other learned professions, including the copying and maintenance of papyri and education through practice.

Some physicians specialized on certain areas of medicine. Both dentists and specialists of eye disorders are attested in stories and in tomb epigraphs. One exceptional papyrus, known as the Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, relates knowledge of women's anatomy, diseases of the reproductive tract, pregnancy, and contraception. The existence of specialists points to hierarchy within the overall medical profession, and different knowledge bases held by people with different training.

The physicians produced by this system were among the most accomplished of their age. The renown for Egypt’s doctors led to calls for their expertise from other societies, from the Hittites to the later Assyrians and Persians.

Mummification

Among the Egyptians, the embalmers who performed postmortem mummification were part of a different tradition of anatomical knowledge distinct from medical practice. Experts in embalming of bodies played a role in every individual’s passage to the next world. In their cosmology, death was a transition to a new beginning, in which the deceased would have need of their body, sustenance, and possessions. This led to enormous investments of skill and effort in the preservation of corpses.

The mummification process lasted around 70 days and involved intricate steps that required detailed knowledge of the human body. The purpose was spiritual, but even so, the work gave embalmers hands-on experience with anatomy.

A key part of mummification was brain removal. Embalmers went in through the nose with long metal probes, breaking through the thin ethmoid plates or the sphenoid bone into the cranium, usually from the left nostril. They then removed the brain using long hooks.

Another step involved cutting into the left side of the abdomen to take out organs like the liver, stomach, lungs, and intestines. These organs were dried and placed in jars protected by gods. The heart was usually left in place. After removing the organs, the body was dried with a salt called natron to stop decay. Embalmers would then fill the body with materials like linen or sawdust to give it a lifelike shape, and wrap the body in linen strips.

Over time, repeating this process gave the embalmers a lot of practical experience with human bodies. Still, their knowledge was based on ritual and practice—not on repeated study of how the body works.

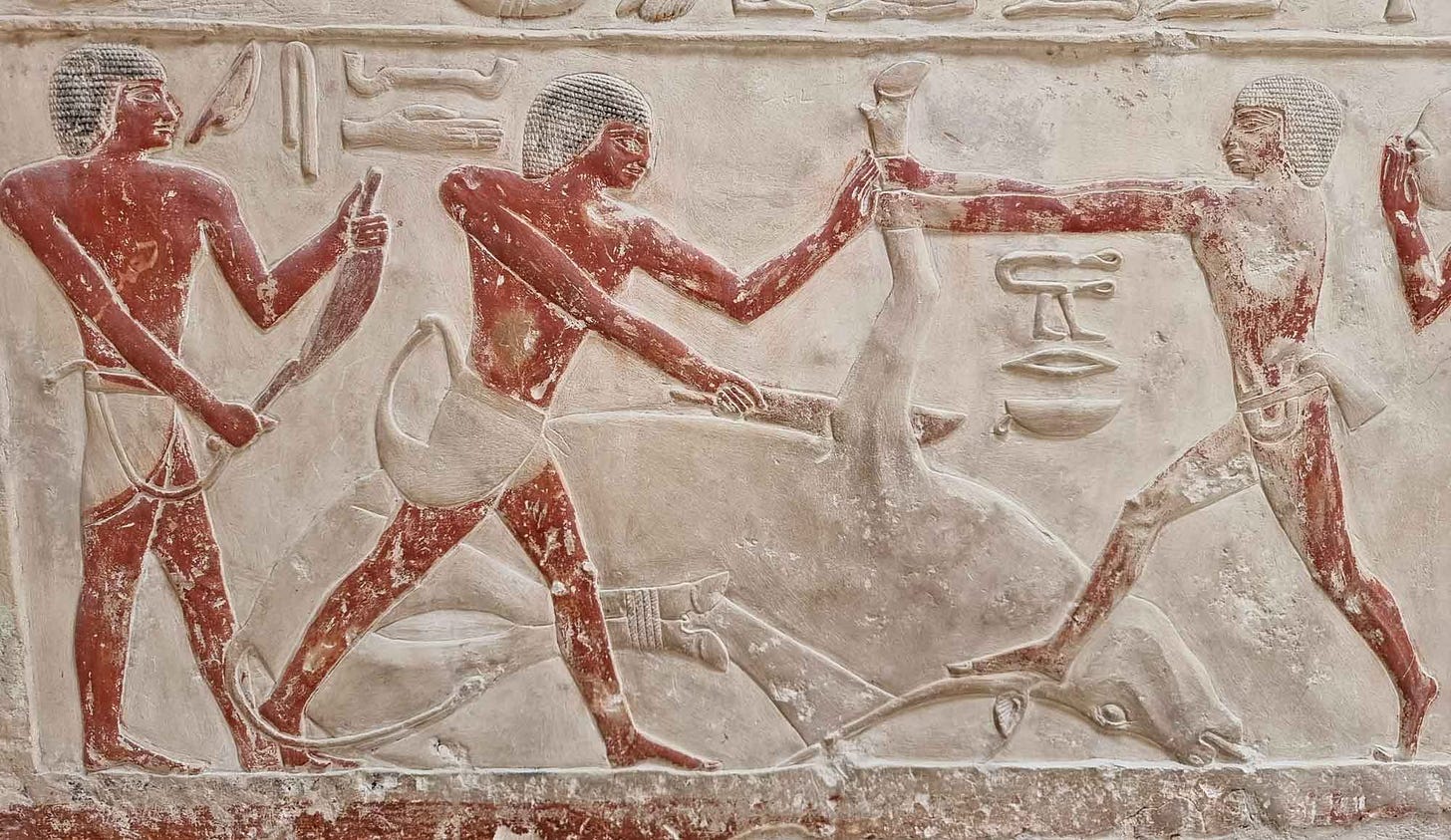

Butchery and animal sacrifice

The oldest and most widely shared anatomical knowledge across human societies comes from the butchery of animals. Every person that kills for food plays a part in renewal of this knowledge.

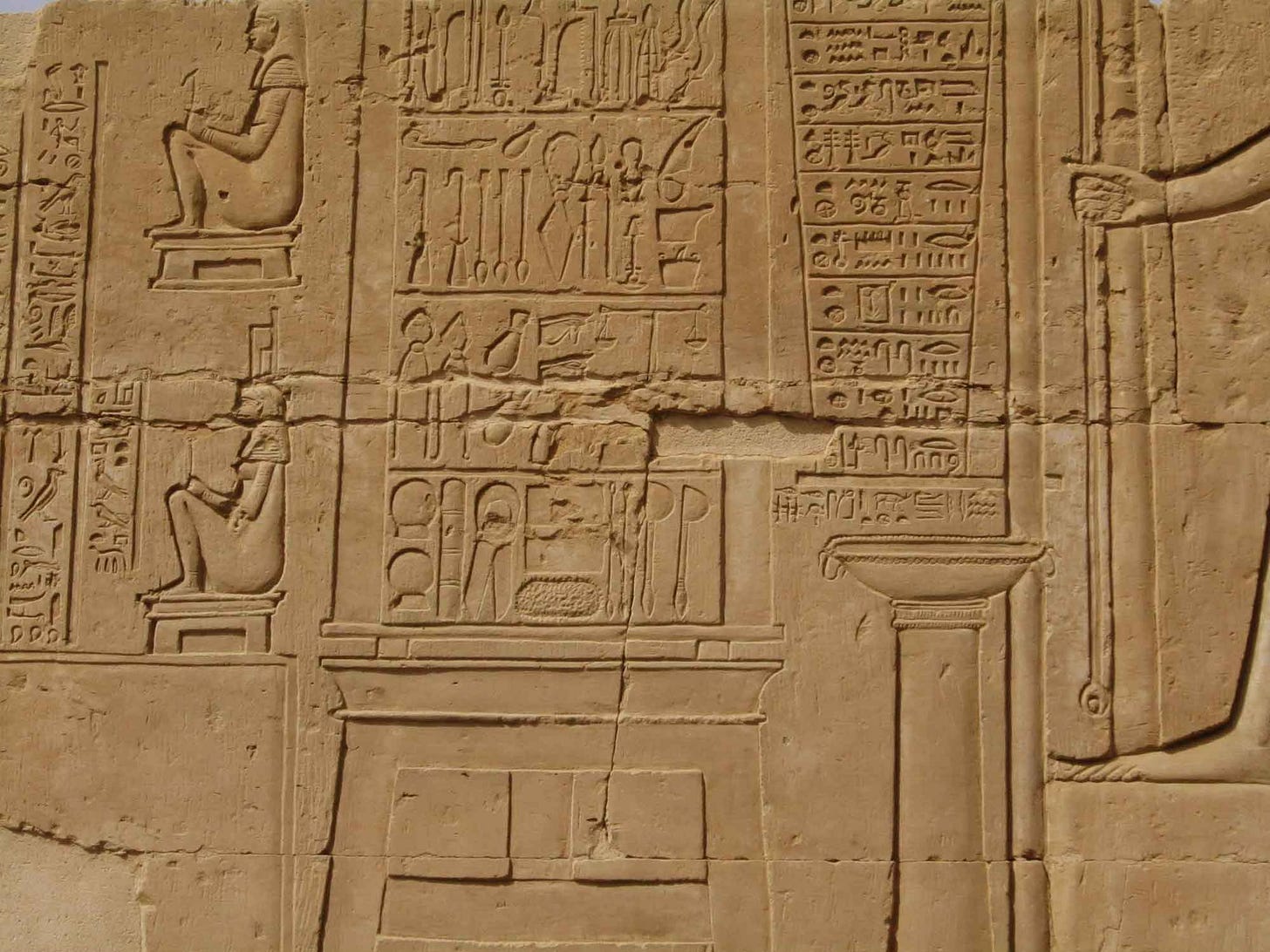

It is impossible to slaughter animals without seeing that they share anatomical structures, which are also shared with humans. The late anatomist Alexander Cave reviewed the development of anatomy in ancient Egypt in an article published in 1950, including more than 100 terms for anatomical structures then known from texts. Cave made special note of the similarities with which the Egyptians referred to the organs of humans and other animals, from bladder and stomach to cerebral convolutions and meninges.

“It is significant that the Egyptians wrote these terms [for organs] with animal determinatives, thus manifesting their recognition of the homology between human and animal organs and incidentally proclaiming themselves the earliest comparative anatomists.”—Alexander Cave

Pharaonic Egypt was one of many societies where people not only ate animals but also killed them in religious sacrifices. Tombs and temples include a number of scenes of animal butchering. They followed a step-by-step process: bringing the animal down, cutting its throat, severing the foreleg, skinning, removing the organs, and cutting the body into pieces. Priests would examine the animal’s organs, especially the liver, to ensure it was healthy and acceptable for offering to the gods.

The veterinary scientist Calvin Schwabe, writing with the Egyptologist Andrew Gordon, considered the ritual slaughter of cattle as having special relevance to the Egyptian understanding of anatomy and physiology. Schwabe noted the specific sequence of dismembering would have brought a number of physiological processes into possible observability by priests involved in sacrifice.

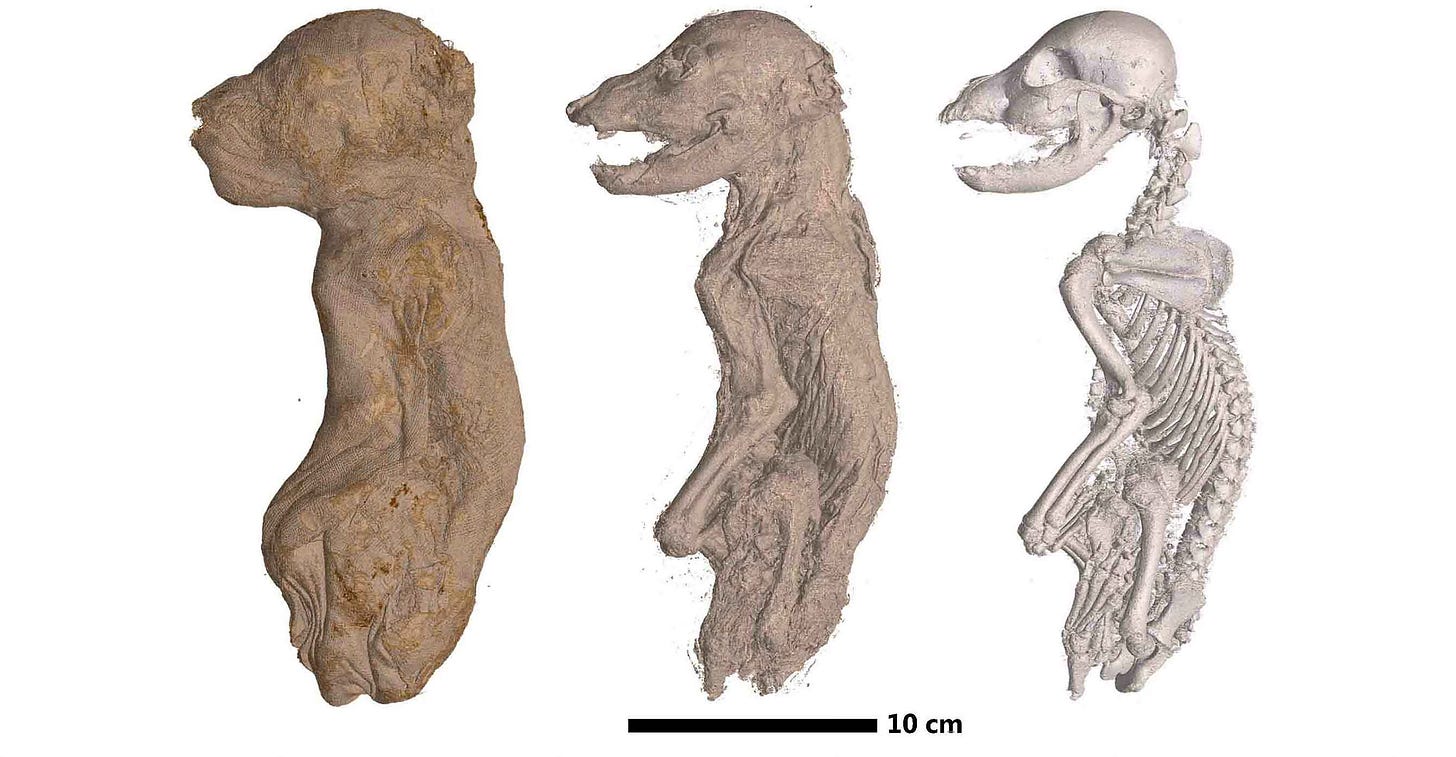

Embalmers, too, worked on animal bodies. From crocodiles and cranes to cats and baboons, nearly every vertebrate in the Nile world was sometimes mummified. Some were beloved pets, some sacred animals worshipped in their lifetime, others were offerings to sustain deceased humans or votive offerings to deities. By the later periods of Egyptian history, animal mummies began to far outnumber human ones.

Magic or science?

The ancient Egyptians saw health as spiritual and integrated with the physical world. They prescribed herbal remedies and potions, magical objects, and magical incantations. It’s doubtful that medical practice in ancient Egypt could have persisted or have developed to such a degree without being strongly rooted in religious practice.

“Ancient Egyptians…did not see a strict dichotomy between medicine and religion. For them, health and illness were manifestations of a person's relationship with the universe around him, a universe that included not just people and animals but spirits and gods as well.”—Laura Zucconi

At the same time, religion imposed some limits on the development of anatomical knowledge. The imperative to preserve corpses as intact as possible prevented observations from dissection or autopsy of human bodies. Dissection was a cornerstone of the development of scientific anatomy, because it enabled observations to test theories of function and development.

Only in the Hellenistic period after 300 BCE did a brief tradition of anatomical dissection arise in the city of Alexandria. This later medical tradition would itself be important to the anatomical and medical knowledge of the Mediterranean world of Classical times, but these developments stood apart from earlier traditions.

Direct observation of traumatic injuries was certainly a valuable natural laboratory. So was butchery of other animals. But building knowledge by analogy from nonhuman animals led to some misconceptions. For example, the sign for uterus took on the bicornate form found in some other mammals. From their knowledge base the Egyptians recognized most internal organs and described the heart's connection to a network of vessels. Still, they did not develop a clear understanding of how blood circulated, or the distinction of blood circulation from other fluids or nerves.

Nowhere is the spiritual nature of anatomical knowledge more evident than in the Egyptians’ approach to the brain. From the Edwin Smith Papyrus we know that physicians saw behavioral effects from injuries to the brain, from aphasia to weakness or paralysis of parts of the body. Three thousand years later, these kinds of observations would ultimately give rise to neuroanatomical science.

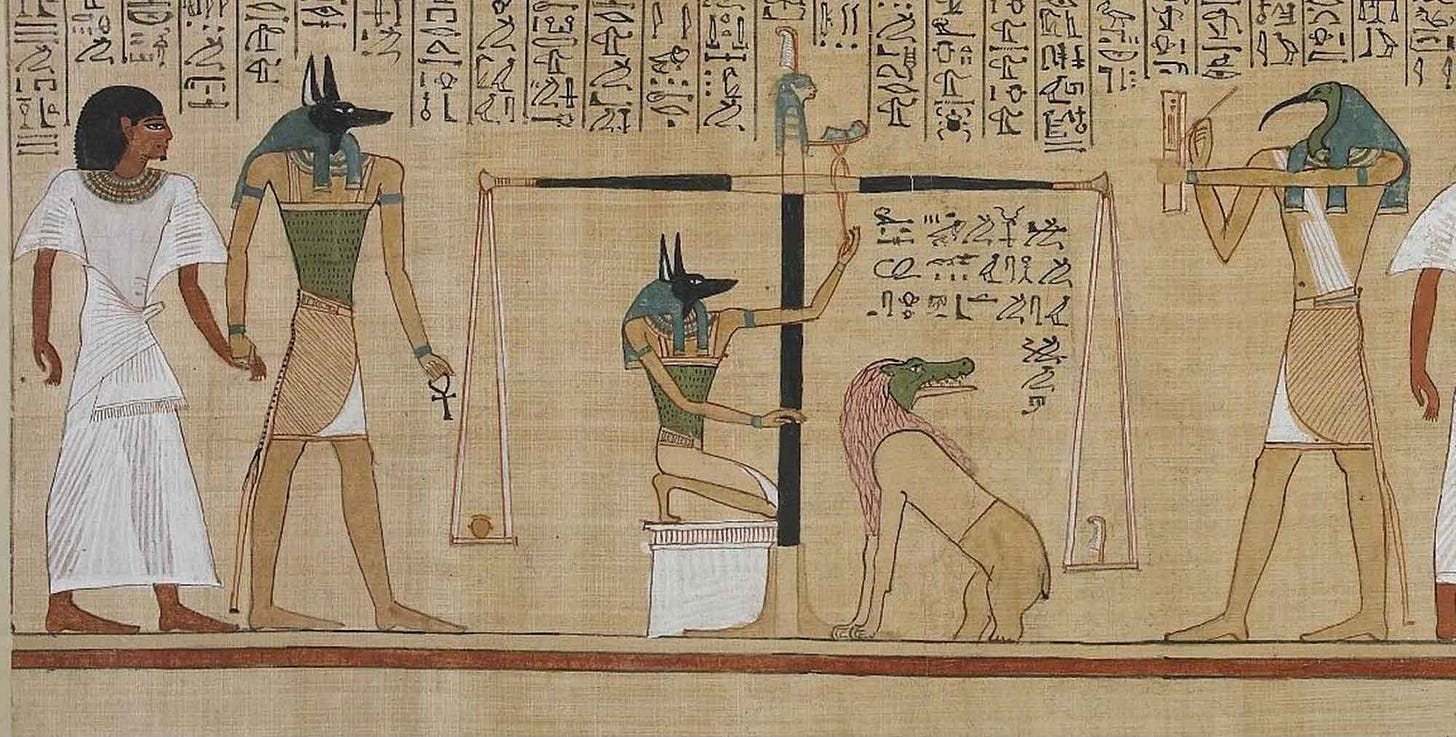

But for the Egyptians, the brain remained an uninteresting blob of tissue. Instead it was the heart that Anubis would weigh on the great scale against a feather to measure its worth. Its weight was not physical, it was spiritual.

Notes: My discussion of the Edwin Smith Papyrus and the translated fragment owes much to the article by Gonzalo Moreno Sanchez and Alwyn Burridge.

There are many directions this essay could have taken. To me, the sheer breadth of the traditions in a civilization that numbered in the millions of people is so impressive. There are thousands of papyri still remaining, yet these are a tiny portion of the vast literature that existed in the Middle Kingdom period across all of Egypt. The analogy to the archaeological record more broadly, with so few fragments of evidence of so many kinds of behavior, is one I hope may help others understand the limitations on our knowledge of traditions and practices in the past.

Alexander Branowski, in an article considering the Edwin Smith Papyrus, suggests that the intent of physicians who used the manuscript was not necessarily to develop the best treatment. Many of the recommended treatments were at best palliative, and the outcomes would depend on the nature of the injury, not the skill of the physician. Instead, the physician’s role was to provide a prognosis, to guide next steps spiritually as well as physically. To the Egyptians, the script itself had a supernatural strength.

References

Blomstedt, Patric. (2020). Anatomy and its importance for surgery in ancient Egypt. History and Philosophy of Medicine, 2(3), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.12032/HPM20200725015

Brawanski, A. (2012). On the myth of the Edwin Smith papyrus: Is it magic or science? Acta Neurochirurgica, 154(12), 2285–2291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-012-1523-x

Cave, A. J. E. (1950). Ancient Egypt and the origin of anatomical science. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 43(7), 568–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591575004300720

Fowler, R. C. (2024). The Practice of Medical Dissection in Third-Century BCE Alexandria, Egypt as a Heterotopia of Deviation. Social History of Medicine, 37(2), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkad085

Gordon, A., & Schwabe, C. (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. BRILL.

Sanchez, G. M., & Burridge, A. L. (2007). Decision making in head injury management in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. Neurosurgical Focus, 23(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3171/FOC-07/07/E5

Tanti, M., Berruyer, C., Tafforeau, P., Muscat, A., Farrugia, R., Scerri, K., Valentino, G., Solé, V. A., & Briffa, J. A. (2021). Automated segmentation of microtomography imaging of Egyptian mummies. PLOS ONE, 16(12), e0260707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260707

Tondini, T., Isidro, A., & Camarós, E. (2024). Case report: Boundaries of oncological and traumatological medical care in ancient Egypt: new palaeopathological insights from two human skulls. Frontiers in Medicine, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1371645

Wysiadecki, G., Varga, I., Klejbor, I., Balawender, K., Ghosh, S. K., Clarke, E., Mazur, M., Dubrowski, A., Bonczar, M., Ostrowski, P., Orkisz, S., & Żytkowski, A. (2024). The most ancient sources of anatomic knowledge. Translational Research in Anatomy, 35, 100295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2024.100295

Zucconi, L. M. (2007). Medicine and Religion in Ancient Egypt. Religion Compass, 1(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2006.00004.x