Sparking ancient fires

New research helps to show the challenges of documenting ancient firemaking

When I was a kid, I spent an unusual amount of time making fires with flint and steel. We had races to see who could ignite a fire the fastest, building it up to boil water first, or to burn high enough to sever a string.

A lot of people have misconceptions about firemaking. Some of those ideas come from watching competition reality shows like Naked and Afraid or Survivor. Producers often supply contestants with a “flint” that works magically well. This is actually a commercial firelighting device for survivalists, using magnesium shavings that ignite readily at a spark and burn at 3000°C. In other words, they cheat.

Neanderthals didn’t cheat. They did sometimes strike fires from sparks. They didn’t have steel but they did have iron pyrite for sparking.

I’m prompted to write about firemaking this week because Nature has published some new research from the Barnham site, northeast of Cambridge, England. Rob Davis and collaborators report on evidence of pyrite firemaking in a 400,000-year-old site. There are no hominin skeletal remains at the site, but based on the date the evidence likely was left by early Neanderthals.

This research is getting some attention as the “earliest evidence of ignition”. Some headlines say that the study “pushes back” the evidence for firemaking by a quarter million years. I think the findings are indeed very cool, but I don’t interpret them in this way at all.

Smoking guns are rare at murder scenes

Archaeologists have found extensive evidence for hominin management of fire from many earlier sites, some a million years and more earlier than the Barnham site. In the earliest phase, before around 800,000 years ago, there are a half-dozen sites in Africa and the Levant with fire evidence. After 800,000 years ago, sites become widespread in Africa, Europe, the Levant, and East Asia.

Just before the Early-Middle Pleistocene transition is the site of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel, around 790,000 years old. This site on the bank of the Jordan River preserves an intricate record of repeated hominin-controlled firebuilding, with charred remains of food plants and fish.

The Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site provides an unparalleled record of fire as a cultural reality for the hominins. As at the Barnham site, the lack of hominin skeletal remains leaves us unsure which hominin group or population made the fires. But their lives revolved around fires in many ways: they used botanical knowledge to choose wood, they worked to gather and transport wood, they brought foodstuffs together for cooking, and their world of smell and taste was one of cooked foods and smoke. They structured their activities around the fires, very much like recent foraging peoples.

Despite the very strong evidence for control and manipulation of fire at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, there is no evidence to suggest how the fires were first started. No smoking gun.

Some archaeologists have emphasized ignition of fire as a major advance that required greater cognitive planning than controlling fires. But this ignores the logistics of fire as a functional part of a society’s subsistence economy.

Consider what is needed to have fire function for cooking, light, or heat. You have to manage the logistics of fuel for the fire. That means transporting wood to the exact location where you want to burn it, at least enough to keep the fire going long enough to go out for more. You have to have familiarity of which kinds of wood are suitable for burning, distinguishing fuel from both green and rotted wood, usually focusing on tree species that burn well and without noxious smoke. You have to manage the gathering of dry tinder and kindling, and you need an understanding of how to use these materials in sequence to allow the fire to start small—from a single coal—and grow.

Not all these have to happen perfectly, of course. The process tolerates much variation. But if we have evidence that an ancient society was shaping its activities around fire, then fire was certainly reliable. It could not be reliable if the logistics went wrong very often.

In the context of human fire use, being able to ignite a fire from sparks or friction is a failsafe. Human societies that rely daily on fire for heating and cooking mostly build them from hot coals that are retained from earlier fires. When people want to build a fire somewhere new, they can transport smoldering coals safely in pouches or containers that are lined with insulating materials.

People who rely on fire don’t strike a new fire every time they want one. Most fire is conserved—curated. Rekindling a fire from a smoldering coal is a bit easier than starting from friction or from a spark, but the steps involved are very much alike.

So why hasn’t there been more evidence for how fires were started? In paleoanthropology, the “first” evidence of a behavior often is more indicative of archaeological visibility than the behavior’s evolutionary breadth and origin. Evidence for fire is unlikely to preserve, evidence for friction or sparking as a way of starting fires is even less likely to preserve.

Even minerals are perishable

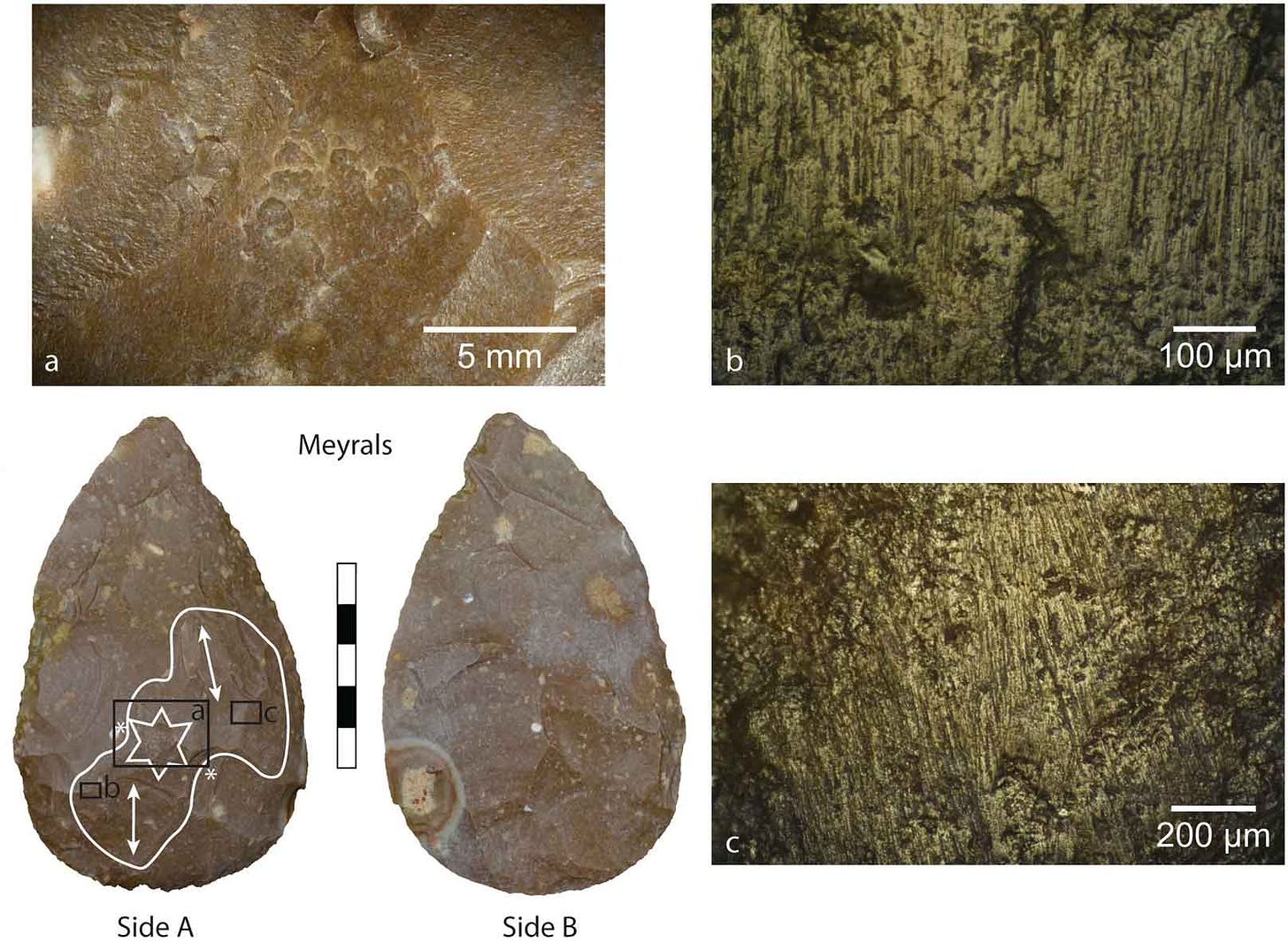

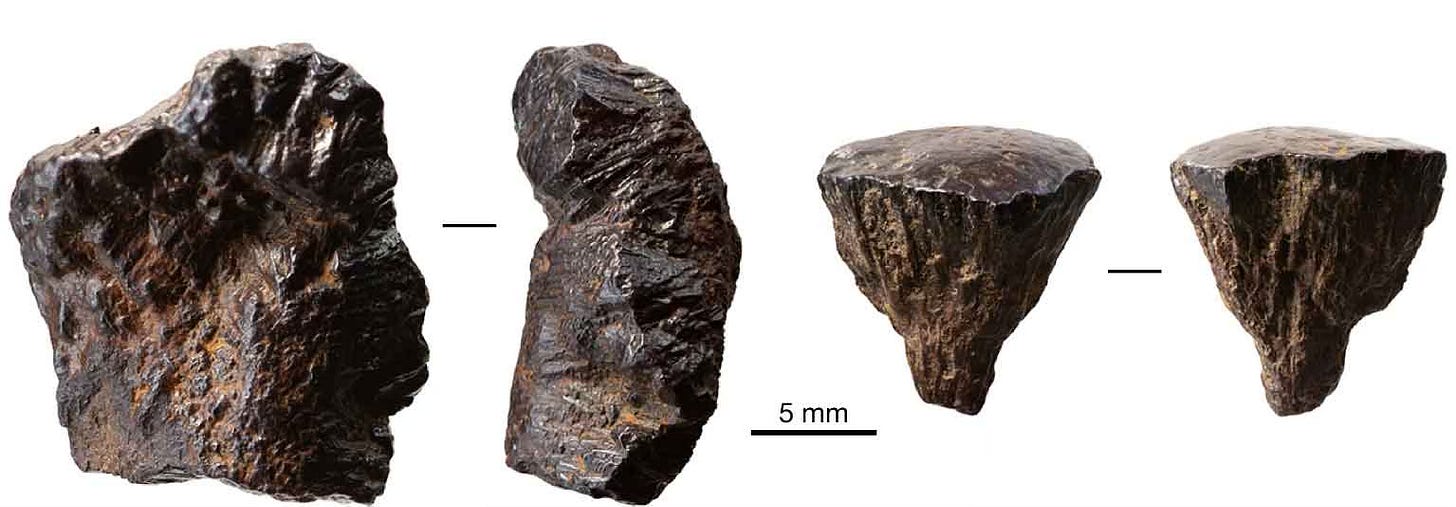

The new study by Davis and coworkers is a valuable example of just how unlikely it is for archaeologists to find the “smoking gun” for firestarting. At the Barnham site, the evidence for knowledge of firestarting is two small chunks of pyrite. One was found in the same level as the fire-reddened sediment interpreted as a fire feature. The other was a surface find.

There are some important details that most reporting has missed. First, the ancient pyrite at the Barnham site is not literally pyrite. Instead, these are “pyrite pseudomorphs”—originally chunks of pyrite (iron sulfide, FeS2) that were oxidized into goethite (FeOOH) and hematite (Fe2O3), presumably after they were buried. The reason Davis and coworkers surmise that these small chunks were once pyrite has to do with their current shape, which retains the textural appearance of crystalline pyrite.

The pyrite itself is gone. In other burial contexts, the retention of a pyrite crystalline appearance after oxidation would be unusual, or would be unrecognized in smaller fragments. In archaeology, it’s common to recognize that organic materials undergo decay and loss over time. But even rocks are affected by diagenetic processes and may be transformed and disappear.

I’ll add that even presence of pyrite fragments does not show that this particular fire was started by hominins. Instead, this study assumes that because the pyrite pieces were near the fire, that the hominins were likely familiar with the flint-pyrite method of fire starting.

Their interpretation draws upon earlier work, especially by Andrew Sornesen, who over the last decade has advanced the scientific understanding of the flint-pyrite method of firestarting. Writing with Marie Soressi, Sorensen has documented intense scratches in small patches on the site of flaked flint artifacts, interpreted as the result of sparking pyrite off the flint.

The later sites with this kind of evidence have mostly not preserved any pieces of pyrite; the Barnham site has preserved no flint artifacts with such traces. Only by putting the pattern together across these hundreds of thousands of years does the story seem to appear.

Fire evidence is growing

I don’t want to leave the impression that I have a negative attitude toward this new work. I think it’s ingenious and I’m especially gratified that the archaeologists were careful enough to notice and preserve these small pieces of pseudopyrite.

What I find a little frustrating is the relentless emphasis on the “first” evidence of starting fires, as if that had been in doubt.

Now to be clear, there remain some archaeologists who take a highly skeptical attitude toward hominin firemaking capabilities. When I was a student, there were some who argued—vociferously—that Neanderthals had no ability to start fires. Those days are thankfully past. Still, even today there are some who suggest that hominins may have controlled fire for hundreds of thousands of years but only by curating fires that were started by lightning.

Poppycock. That “quest for fire” nonsense is a fictional way of looking at the past.

The record of ancient fire that archaeologists gathered across the last century is weak in some important ways, and many specialists have been working to improve the record. Where color changes in sediment were once accepted as compelling evidence for fires, today researchers can apply FTIR, environmental magnetism, and microscopic analysis of sediment to add precision to the data. These approaches have indeed revealed a few cases where the original interpretation of fire is no longer supported. More often, they have helped solidify the evidence or brought attention to cases that were missed. A fascinating paper from last year by Ángela Herrejón-Lagunilla and coworkers uses magnetic evidence to show the timeline of a series of fires made in the same site, giving an unparalleled evidence about the duration of traditions of fire within a Neanderthal society.

Fire can be hard to find, and evidence for starting fires even harder. But archaeologists are better and better at meeting this challenge. As they have done so, they have uncovered a depth of relationship between fire and human ancestors that mattered to our evolutionary pathway. Ancient hominins cooked foods to release energy, to strip toxins from otherwise-inedible plants, or simply to taste better. They systematically burned some landscapes to attract game. Those behaviors started much earlier and were adopted much more broadly than we once thought.

I’ll end with a fascinating anecdote from Andrew Sorensen’s work. Chunks of a black mineral called manganese oxide have been found in many Neanderthal sites, some with clear friction or rub marks on their surfaces. They have usually been interpreted as pigment, some with evidence of rubbing on skin or hide.

But Sorensen realized that manganese oxide has interesting properties when burned. Sparking pyrite into a small pile of this powder would create a very hot fire—not so different from the survivalist tools on reality TV.

In other words, maybe even Neanderthals cheated sometimes.

References

Davis, R., Hatch, M., Hoare, S., Lewis, S. G., Lucas, C., Parfitt, S. A., Bello, S. M., Lewis, M., Mansfield, J., Najorka, J., O’Connor, S., Peglar, S., Sorensen, A., Stringer, C., & Ashton, N. (2025). Earliest evidence of making fire. Nature, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09855-6

Herrejón-Lagunilla, Á., Villalaín, J. J., Pavón-Carrasco, F. J., Serrano Sánchez-Bravo, M., Sossa-Ríos, S., Mayor, A., Galván, B., Hernández, C. M., Mallol, C., & Carrancho, Á. (2024). The time between Palaeolithic hearths. Nature, 630(8017), 666–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07467-0

Sorensen, A. C. (2024). Lucky strike: Testing the utility of manganese dioxide powder in Neandertal percussive fire making. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 16(8), 134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02047-9

Sorensen, A. C., Claud, E., & Soressi, M. (2018). Neandertal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 10065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28342-9

Intuitively I imagine one of the possible mode of long preservation of fire traces could be soot on the ceilings and walls of caves and rock shelters. I wonder if there are many archaeological finds line this and how deep in time do they go?

Excellent. I have wondered about how fires were started and “curated” since I was a child. I never had much luck with flint and steel despite many untutored efforts. The following statement caught my attention: “When people want to build a fire somewhere new, they can transport smoldering coals safely in pouches or containers that are lined with insulating materials.” Is anything known about what materials were used? I suppose rocks, gravel, sand and dirt would all work. Nonetheless, carrying fire without metal tools sounds precarious.