Ten years of Homo naledi in my world

I reflect on the experience since the scientific description of the species was published in 2015

On September 10, 2015, I was in South Africa helping to launch a new species. On that day our collaborative research describing Homo naledi was published in eLife.

The fossils had been first discovered nearly two years earlier in September 2013. Steven Tucker and Rick Hunter entered a chamber that had no name and was unmapped, and what they found was fossil bones. The investigation of the site began immediately, with the first excavation and recovery of fossils in November, and the study of the remains commenced. A collaborative workshop in May 2014 with experts from many different areas of anatomy, skeletal analysis, and systematics was a key part of these studies.

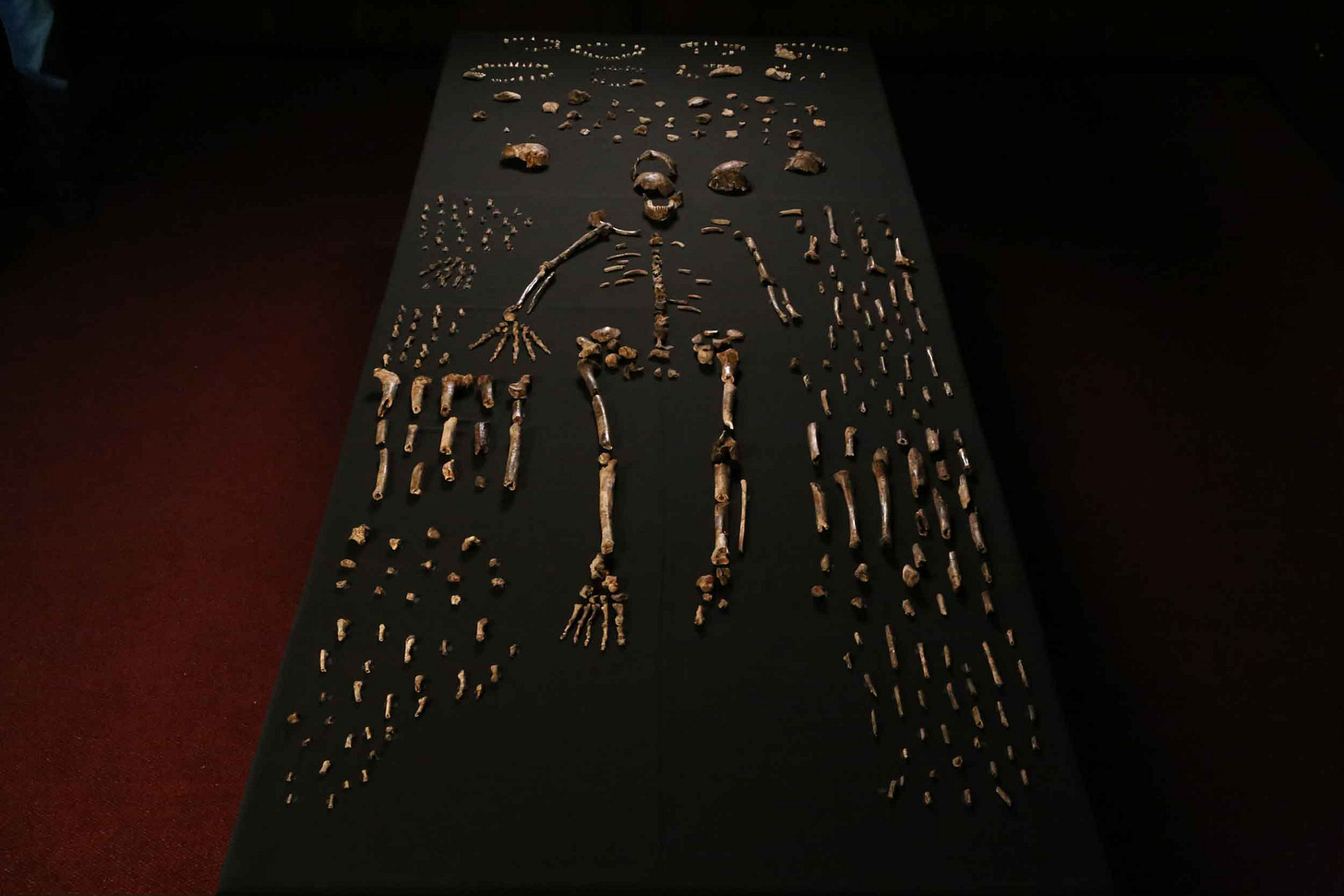

Carrying out the primary analysis of this large collection of hominin fossils in two years was unprecedented. It couldn’t have been done without the open collaboration of more than 45 scientists who brought datasets and expertise on every element of the skeleton. There was of course a vast amount of work still to be done—today we’re still working hard at it—but Homo naledi at the time of its publication was the most abundantly documented species diagnosis ever presented in paleoanthropology.

I’ve told the story of the discovery and subsequent research before, including the incredible teams of scientists who have worked in the Rising Star cave system, and many of their continuing discoveries, including two books coauthored with Lee Berger. The great thing about a book is that you get to name so many of the people, and yet I’ve found that even that isn’t enough to recognize so many contributions. Those stories are still unfolding.

All that was background in September 2015.

The public events that accompanied the release of the research took place at the Maropeng Visitor Centre of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, outside Johannesburg. Cyril Ramaphosa, who for the last seven years has been President of South Africa and in 2015 was Vice President, presided over the announcement. It was my privilege to present the findings on the biology of H. naledi, I was joined by Paul Dirks who discussed the context of the site, and Lee Berger who introduced the new species for the first time.

We had chosen the journal eLife because of its open access format without restrictive limits on length. That proved to be a great decision: Our research articles describing H. naledi and its geological context went on to be downloaded or viewed by more than 400,000 people during the first month after release.

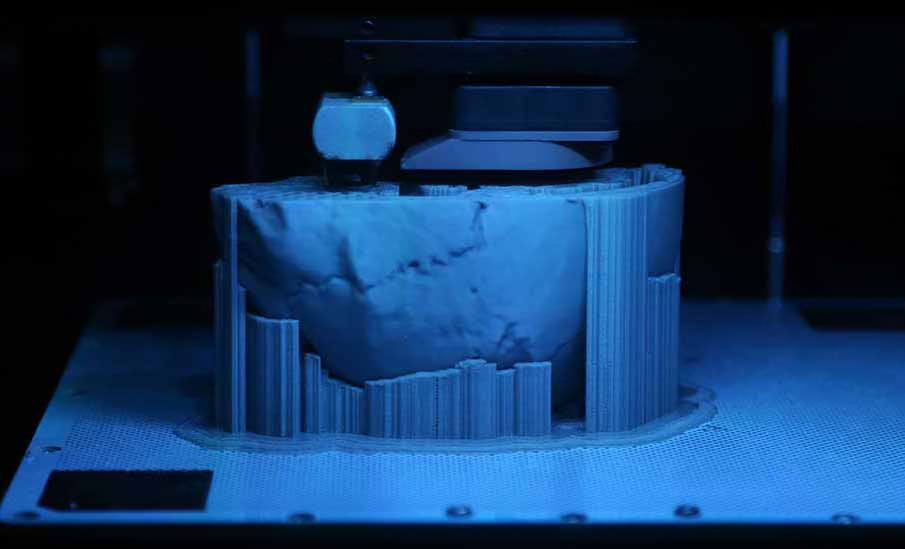

With the collaboration of Wits University and Duke University, our team immediately released high resolution surface scans of H. naledi fossils on the Morphosource site for open download. Researchers and educators from all over the world started printing out their own naledi fossils. Those data are still growing as we study and scan more than 2500 fossil fragments from the cave system.

The open access to H. naledi data and publications led to a massive scientific dividend as our team and others quickly built a vast record of research. Running the numbers, there have been more than 120 research articles written primarily about Homo naledi in the last decade, with more than 2000 citations according to Google Scholar. A vastly larger number of articles have included the H. naledi data in comparative analysis or discussion of other fossils.

We still have a big team which keeps growing. But the research goes far beyond one group of researchers. Many collaborators have followed up their own research tracks, and many others started new research on H. naledi fossils using either the data or access to the original fossils. I’ve actually lost track of how many PhD dissertations have been focused on H. naledi, the Rising Star geology, or other topics that flowed from the discovery.

Naming H. naledi and describing its anatomy was, of course, only a first step. When we presented the fossils to the world, we did not know how old they were. Later we could determine that the fossils in the Dinaledi Chamber were deposited between 335,000 and 241,000 years ago. That put H. naledi into the time frame of early members of our own species, showing a diversity within Africa of human relatives we had not previously recognized. We’re still working out what this means for understanding the ecology and behavior of both H. naledi and early humans.

We also did not have a very clear idea of how these individuals had used the cave system—including, most importantly, what practices led them to leave bodies in such a hard-to-reach part of the cave.

The initial excavations had been limited to a small area within the Dinaledi Chamber. Very quickly team members identified fossils in a distant part of the cave, the area we later named the Lesedi Chamber. After excavations there, we reported the partial skeleton of one H. naledi individual, whom we nicknamed “Neo”, and pieces of at least two more individuals. The team later expanded explorations into more remote parts of the cave near the Dinaledi Chamber, finding some exceptional fossils such as the “Leti” child. The excavations ultimately turned up fascinating evidence relating to how H. naledi used the cave.

That’s a longer story that has been unfolding over the last few years, and I’ve written about a few times. I’ll likely write some more soon as new research is progressing.

These last ten years have changed my outlook on science. I’ve learned a lot.

Homo naledi was neither predicted nor expected by anyone. A site of this kind, with many skeletons of a hominin population but few traces of other species, was not expected by anyone. This is far from the only unexpected find in recent years, there have been many across human evolutionary history that nobody predicted.

What this has reinforced to me is how important it is to keep an open mind. New discoveries cannot change your perspective if your mind is not in a state to see something new or different.

Finding something new and unexpected is the greatest joy that nature has to offer to any scientist. I’m fortunate to keep being involved in discoveries that surprise me. I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say that it’s every time I’m in the field, and more times in the lab than I can count.

That pathway of discovery continues to unfold for H. naledi, and many of the things that have surprised me lately are still occupying my time and thoughts. Hopefully I’ll have more to report very soon.

What are your thoughts on the evolutionary line leading to H. naledi? And why there hasn't been found any predecessor fossils? If they were more arboreal than other humans, perhaps they evolved in more forested environments where fossils might be much more difficult to find.

In regard to the cognitive question, I note studies showing cognitive function mapping more closely to number of neurons than cranial size. Neurons can be packed more or less densely in different parts of the brain and in different species. Perhaps they had a more comparable amount of neutrons to H. sapiens, especially in the frontal areas of brain, than might be thought if we simply compared cranial capacity.