Tracing the wave of Neanderthal-modern interactions

A rapid expansion of modern people ran into Neanderthals and mixed with them nearly to the ends of their range.

Today’s people have some Neanderthal ancestors. It’s remarkable as I think about it, that we’ve known about this ancient connection for the last 16 years.

Narrowing down exactly which Neanderthals those ancestors were is a bigger challenge. Where did they live? Does everyone living today have genetic ancestry from the same Neanderthal group? Or from many different ones? How many were there?

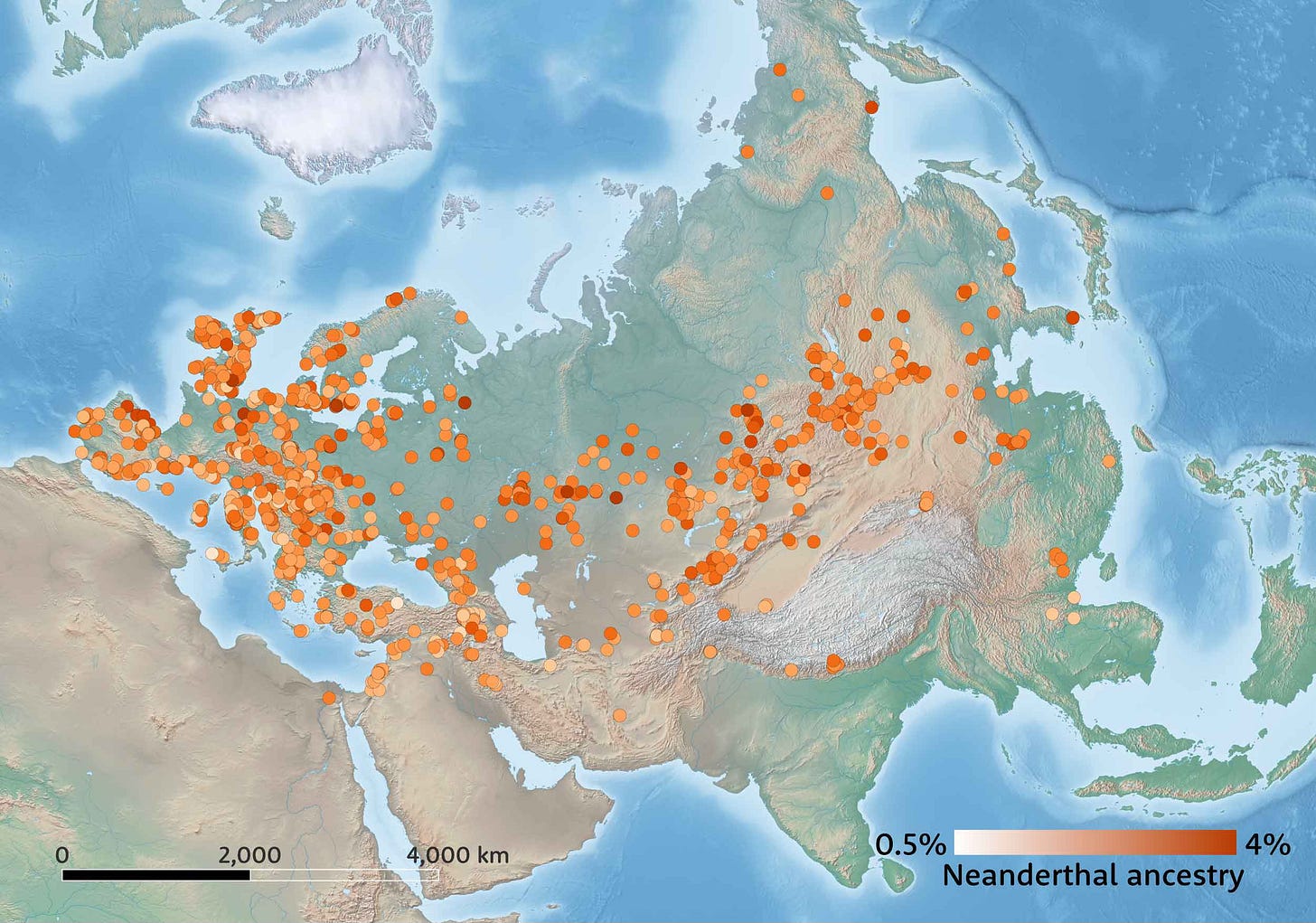

A series of papers from the research group led by Mathias Currat has put a new spin on these questions. These papers use the current dataset of ancient genomes from across Eurasia, numbering more than 4000 individuals in total across the time from 40,000 years ago up to 600 years ago. With this sample it is possible to look at variation in Neanderthal ancestry over both time and space.

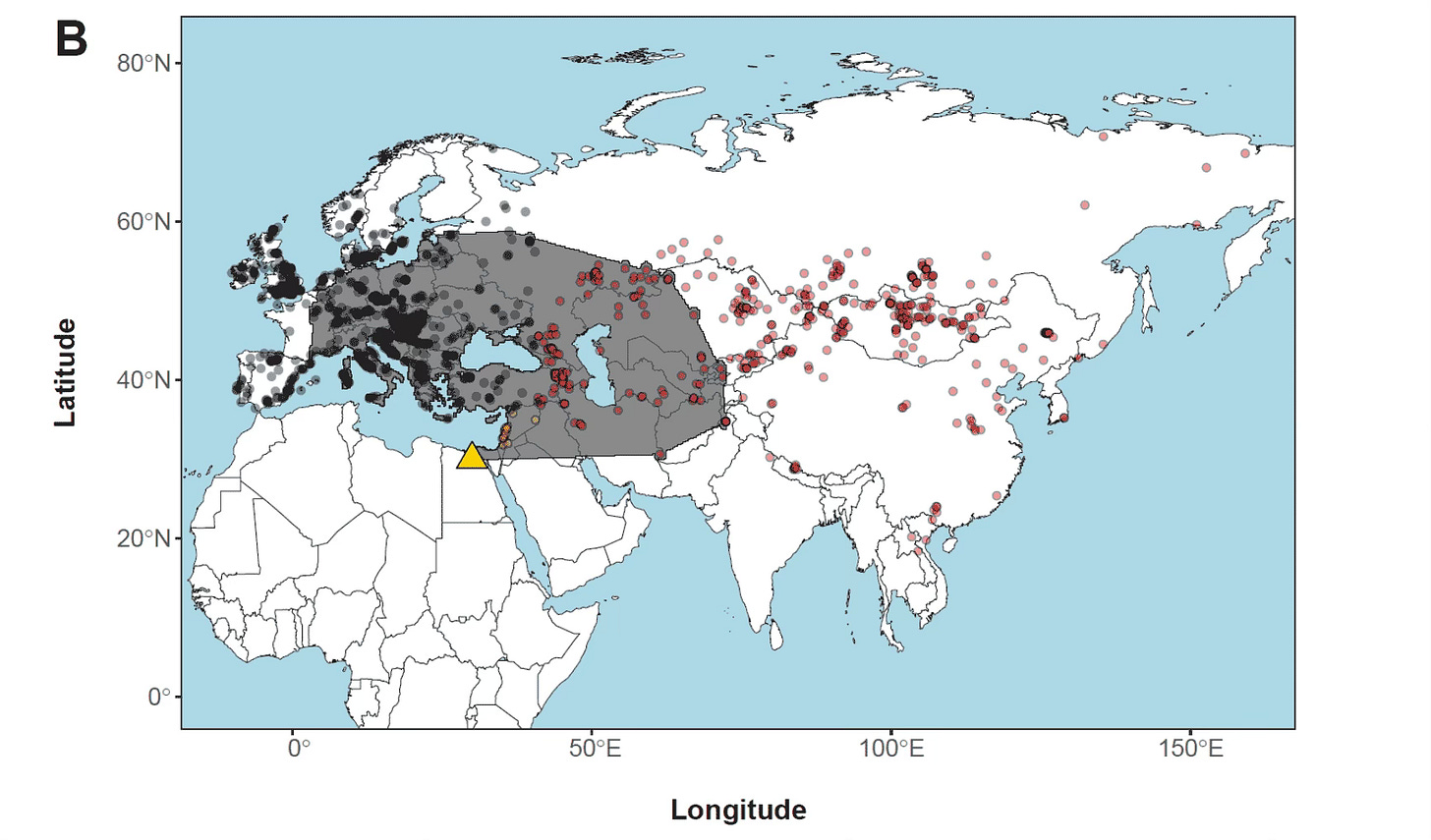

The developing picture suggests that when the early founders of today’s Eurasian populations were mixing with Neanderthals, that mixture was not limited to one small region or group. Instead, the wave of founders spread into the Neanderthals’ geographic range, mixing with the locals across thousands of kilometers. Ultimately that process extended across most of the Neanderthals’ geographic range, from Afghanistan to France.

The first story

When the first ancient genomes were recovered in 2010, researchers first hypothesized that Neanderthal-modern genetic mixture happened only within a very narrow geographic region.

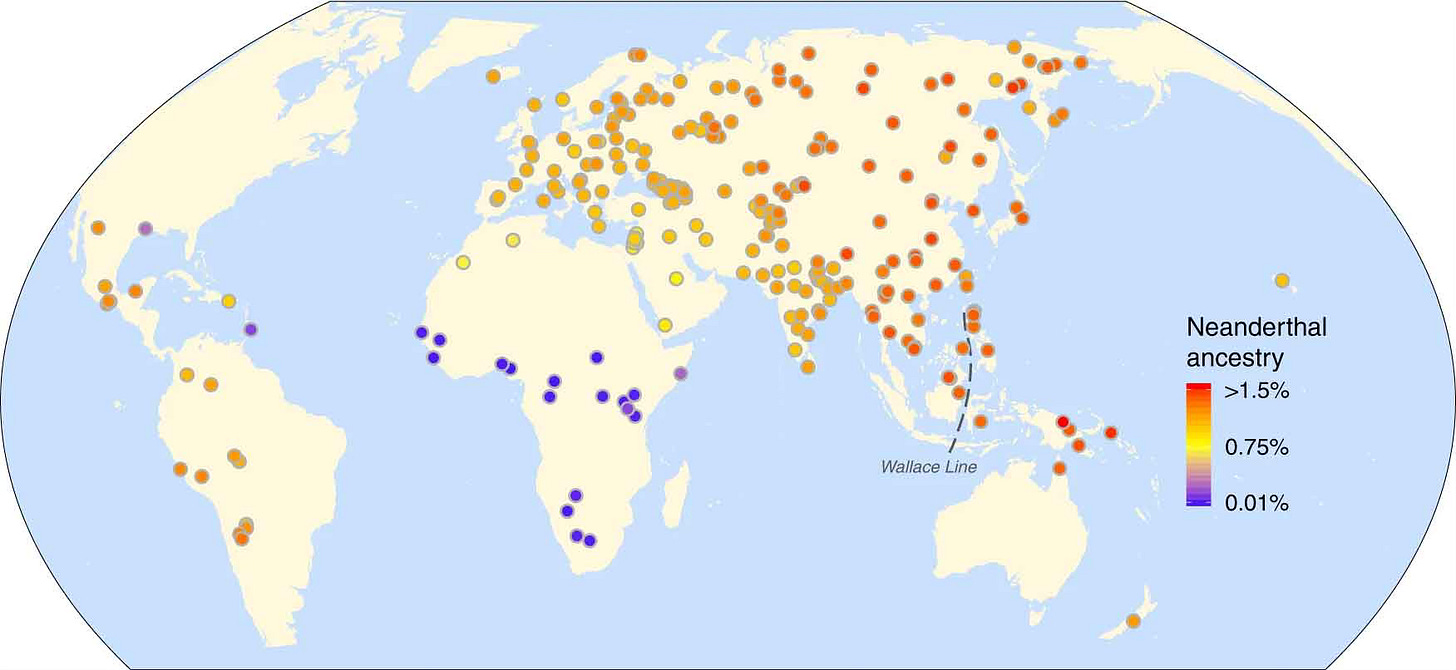

Early analyses showed that the fraction of Neanderthal genetic ancestry was more or less the same in living people across Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. All these people had an estimated 1% and 4% Neanderthal-derived DNA.

Only in Africa were people clearly much lower in Neanderthal heritage, small enough to be undetectable with the first statistical approaches to the question. Today we know that across Africa south of the Sahara Desert, living people have only a trace of Neanderthal genetic ancestry. This pattern is a legacy of thousands of years of migration and mixing between Africa and Eurasia. The level is not very high: a fraction of a percent. Still, the sheer distances involved—some 8,000 km across the continent north-to-south—are a vivid reminder of how gene flow has diffused across groups.

To a lot of people, the Neanderthal inheritance was a surprise. Not me, I expected it. What did surprise me was the seeming uniformity of Neanderthal ancestry in so many parts of the world. After all, the Neanderthals lived in Europe, not China or Australia. Like many people, I thought Neanderthal genes should be most common in Europe.

Altogether, these observations led to a hypothesis: An early founder population got its start in Africa, met Neanderthals somewhere in the Near East, and then dispersed throughout the world. Their descendants carried the same Neanderthal legacy with them everywhere they went. The timing of that mixture coincided with the dispersal, sometime between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia, the expanding wave of people never met any more Neanderthals. They did meet others. Varied branches of modern descendants mixed with several deep lineages that we group together as Denisovans, to different degrees, carrying that DNA forward into Oceania and the Americas.

In Europe, on the other hand, the expanding wave of modern people met Neanderthals at every step. Yet somehow they did not mix any further. Maybe, some geneticists thought, some kind of genetic incompatibility stopped further Neanderthal genes from being integrated into later people.

An extra dash of Neanderthal

In 2013, Jeff Wall and coworkers shifted the story by showing that East Asian populations have more Neanderthal ancestry than Europeans. That was really the reverse of what people had expected. Again, Neanderthals lived in Europe, not China.

The difference is small but may be consequential. As data have grown, the numbers have solidified to around 0.2 to 0.5% of the genome, which adds up to around 31 million nucleotides. Still, it’s a good deal less than people within each region often differ from each other.

How did that extra Neanderthal ancestry get into East Asian populations? According to one idea, the founder population of East Asian groups was smaller in numbers than the west. With higher genetic drift, purifying selection was less effective in weeding out many slightly deleterious Neanderthal gene variants. They persisted, where in other parts of Eurasia they disappeared. Another scenario proposes that when the original out-of-Africa founders split into eastern and western branches, the eastern branch met another group of Neanderthals and picked up a small extra burst of DNA.

Other researchers suspected that the dash of extra Neanderthal might be a statistical illusion. Researchers might conceivably have been misrecognizing genes from Denisovans. Or maybe the longer average haplotype lengths across genomes in East Asia—a legacy of the founder effects early in modern human arrival to the region—meant that geneticists were slightly underestimating Neanderthal haplotypes everywhere else.

One thing is for certain: the small differences are hard to measure accurately. Making things harder is that subsequent movements and mixtures of people tended to blur the patterns that once existed.

The impact of Basal Eurasians

I’ve tended to favor the idea that parts of western Eurasia received an extra burst of African ancestry during the last 20,000 years. My thinking traces back to the partial sequencing of the genome from the Oase 1 individual by Qiaomei Fu and collaborators in 2015. This individual had more than double the Neanderthal ancestry of anyone living today, and the length of haplotypes suggested that the individual’s most recent Neanderthal ancestor had lived just a handful of generations earlier. Later work uncovered other early Europeans with similar recent Neanderthal ancestry, from Bacho Kiro, Bulgaria, and Zlatý kůň, Czechia. All of these early Europeans had ancestry from the same founder population that ultimately gave rise to most of today’s Eurasian gene pool. But these people who lived at the time of the earliest Upper Paleolithic in Europe made little dent on the gene pool of later Europeans.

It’s probably too much to say that the first waves of dispersal into Europe “failed”, or became extinct. Genetic samples of subsequent Upper Paleolithic groups are too small to test strong claims about replacement of the first peoples. Still, it is clear that living people haven’t got much ancestry from the earliest European groups.

No matter what happened later, the wave of Neanderthal mixture in the first modern Europeans was mostly erased.

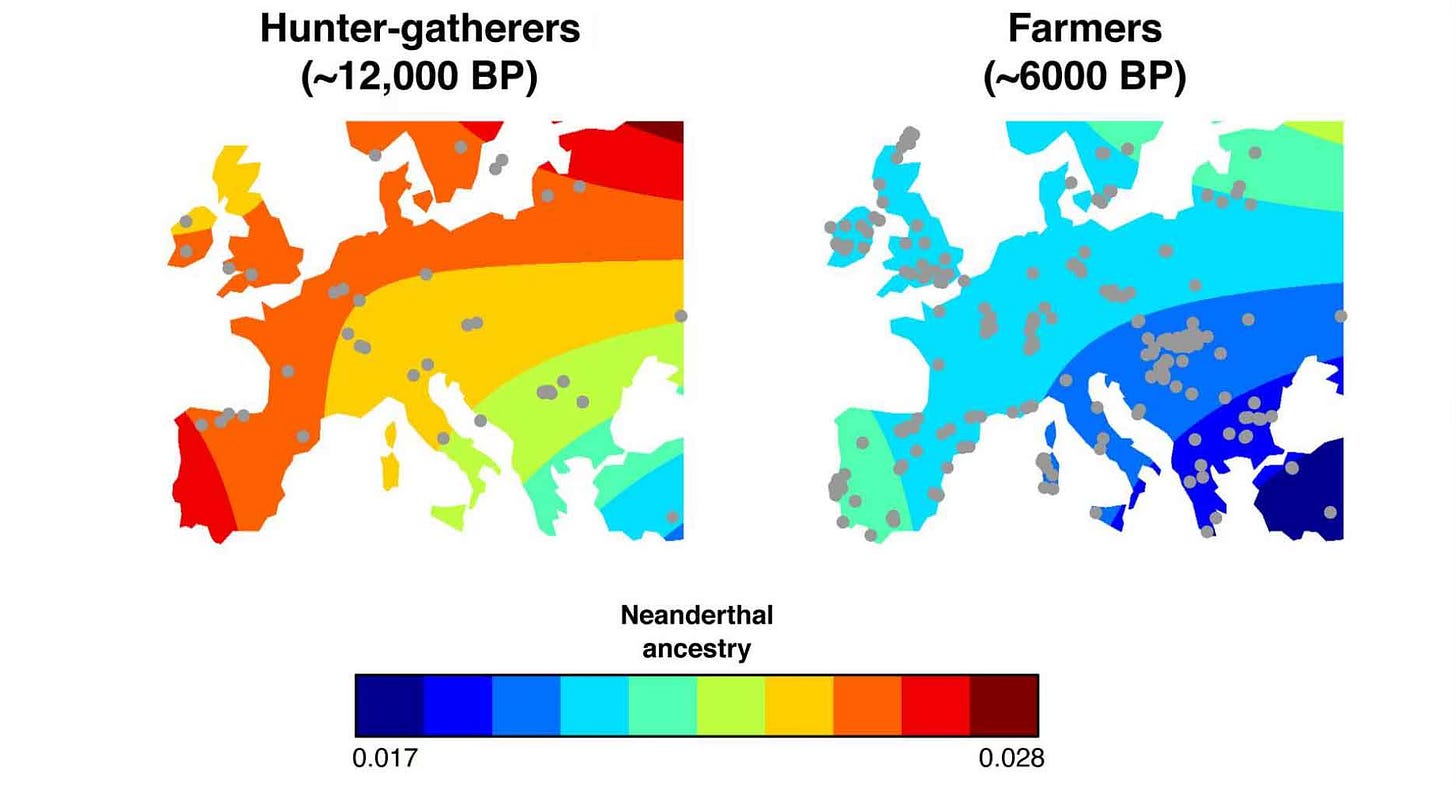

No single event established today’s pattern across western Eurasia. Every wave of newcomers had its own effect. One important influence was the spread of early farmers from Southwest Asia. A series of papers on ancient genomes by Iosif Lazaridis and collaborators, starting in 2014, hypothesized that ancestry from a very early out-of-Africa group—which geneticists call the Basal Eurasians—was important to the populations of Southwest Asia. The Basal Eurasians, possibly stemming from the very first out-of-Africa founders, had a lot less Neanderthal ancestry than other peoples of the continent. That lower Neanderthal ancestry is observed within their descendants in the Levant and Arabia today. The Basal Eurasians made up nearly half the background of Neolithic peoples who brought farming into Europe. With their lower Neanderthal ancestry, the coming of the farmers could have covered up some of the evidence of earlier mixture.

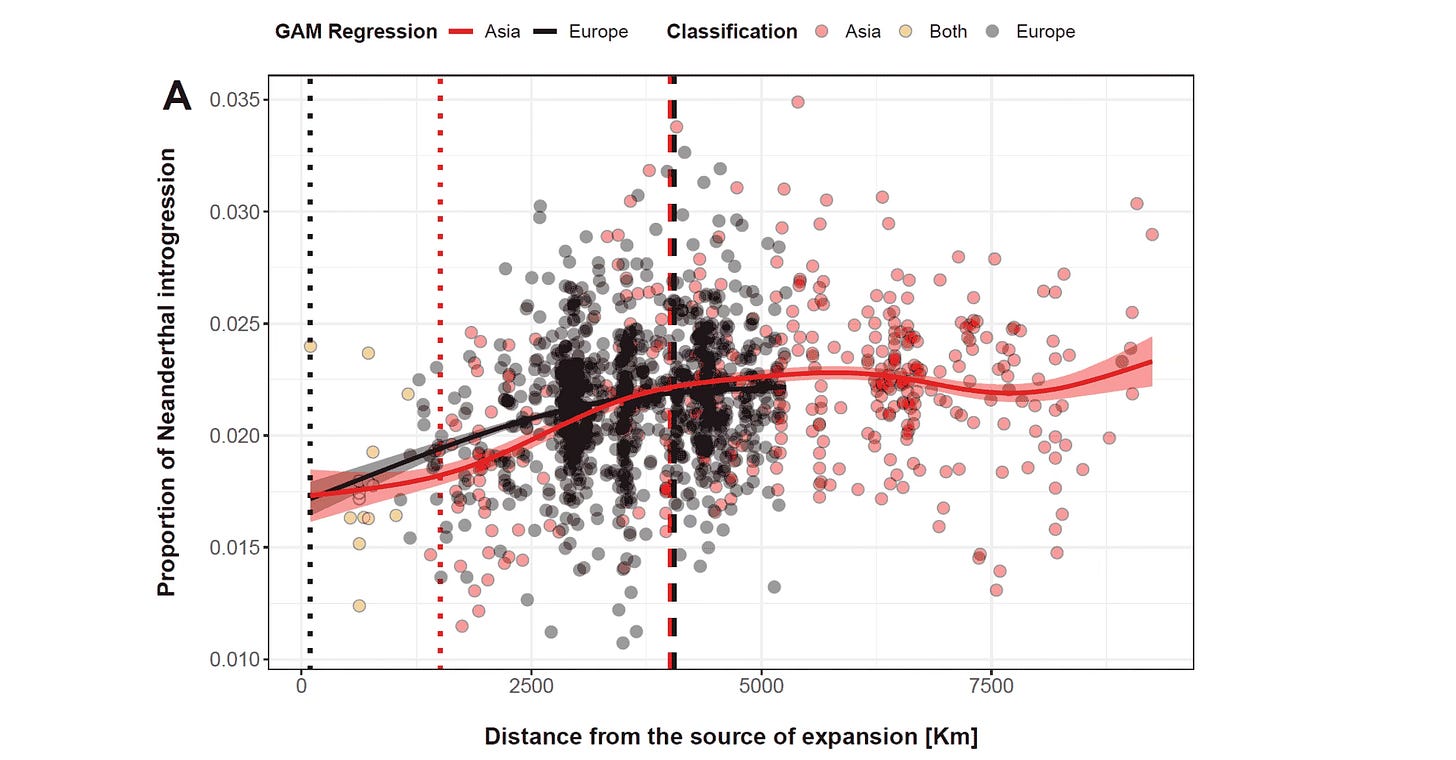

Ancient DNA from early modern Europeans has added enormously to this picture. In a 2023 paper, Claudio Quilodrán and collaborators took the known sample of ancient genomes from across Eurasia, a dataset numbering more than 4000 individuals, and looked at the pattern of Neanderthal genetic ancestry over space and time.

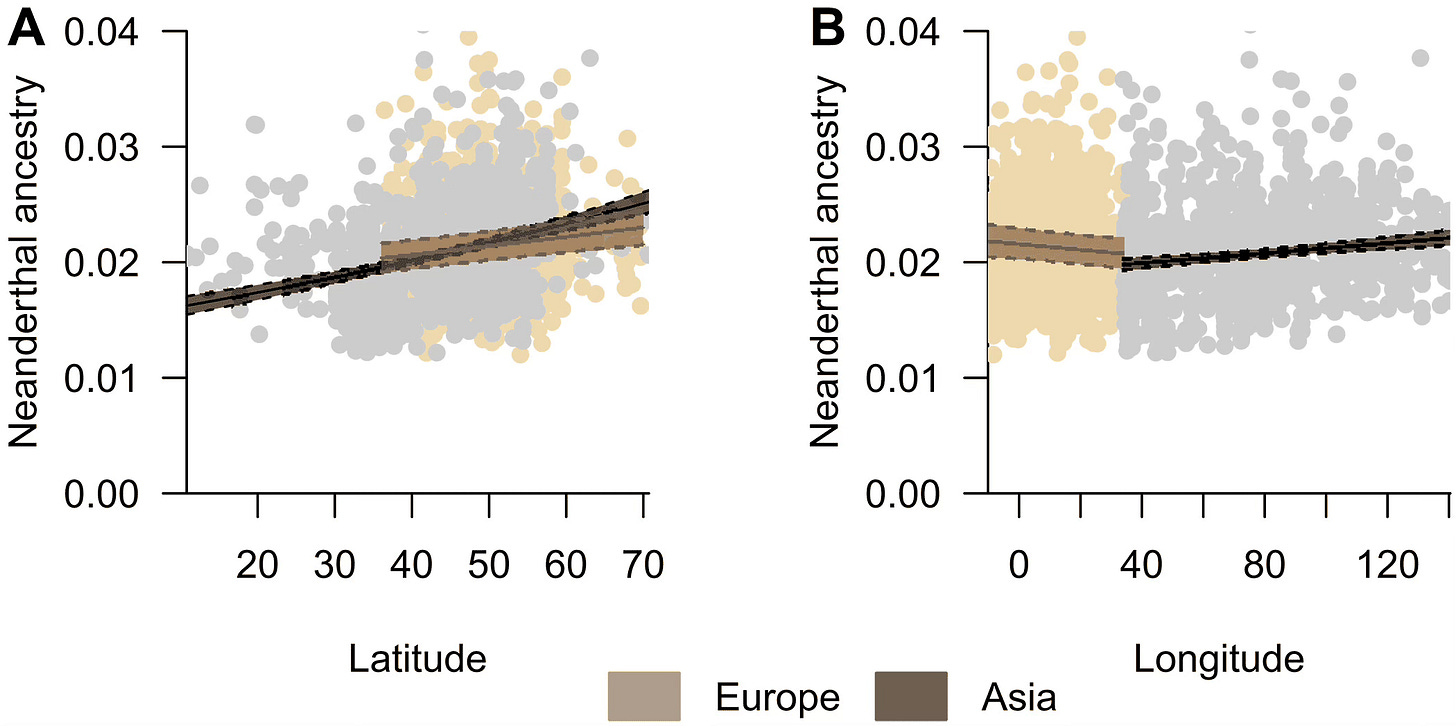

They found many clear relationships. In both Europe and Asia, Neanderthal ancestry forms a slight gradient with higher values at higher latitudes. Going further north, you encounter slightly more Neanderthal ancestry.

In population genetics, this kind of gradient of variation across space is known as a cline. Clines result from processes that mix genes across space. Ultimately genes from different places mix because people move and mate. But whether movement was a massive wave or a slow percolation between two or more populations can be hard to work out.

Ancient genomes help by adding the time dimension. Using the sample of 4000+ ancient genomes, Quilodrán and coworkers were able to show how the cline in Europe changed with the arrival of early farmers. The spread of this group happened around 6000 years ago. By that time Neanderthals were long gone—for more than 30,000 years except possibly at the very extreme in Iberia where they may have persisted a touch longer. Farmers brought along their Basal Eurasian ancestry. That didn’t change the direction of the genetic gradient, but it did cause a reduction of around half a percent Neanderthal ancestry all across Europe.

Today’s European component of Neanderthal ancestry is actually higher than that found in the early European farmers. After their initial arrival in Europe, early farmers mixed with local hunter-gatherers. The genetic makeup of later populations was also affected by the arrival of steppe peoples during the Bronze Age. In the end, today’s complement of Neanderthal genes in Europe was affected by the early farmers only moderately.

A Neanderthal ancestry cline

One of the most valuable figures in the work by Quilodrán and coworkers is the plot of Neanderthal ancestry according to latitude and longitude. The plot is separated into the two continental regions, Europe and Asia, and that separation helps a great deal in recognizing the overall pattern.

Higher latitudes have higher Neanderthal ancestry, as mentioned above. The pattern with longitude has an inflection point. Across Europe, Neanderthal ancestry increases slightly as you go west; across Asia Neanderthal ancestry increases slightly as you go east.

Slight means very slight. In both eastern and western directions, the cline of increasing Neanderthal ancestry adds up to much less than one percent of the genome. The differences between the ends of the cline are much smaller than the variation among individuals at any one geographic location.

Still, a difference of a few tenths of a percent makes up a fair fraction compared to the 1 to 3 percent Neanderthal genetic ancestry that Eurasian people have today and in the past.

A new study from the same research team, led in this preprint by Lionel Di Santo, works to explain how these clines got their start. The team simulated a growing modern population moving step by step across a zone where they mixed with Neanderthals. That stepwise population growth gives rise to a cline as long as interbreeding continues. The further into the zone of mixture, the more Neanderthal genetic input there should be.

In this way, both the latitude and longitude clines can be explained by a wave of advance of modern people, moving into territories occupied by Neanderthals and interbreeding with them along the way.

But there is an important twist. A cline established by an initial wave of advance with mixture should only extend as far as the mixture happened.

To investigate the extent of the clines more precisely, Di Santo and coworkers applied a nonlinear regression model. They found that the European cline keeps increasing almost all the way to the western extreme of Europe, but not quite—it stops in France, beyond which there is no further increase in Neanderthal ancestry. Likewise for the cline’s northern extent, which stops in Germany, well short of Scotland and Norway.

In Asia the cline’s limits are more striking. Neanderthal ancestry increases among the ancient genomes from the Levant to Kazakhstan and northern Pakistan. But further to the north and east there is no further increase in Neanderthal ancestry. Across the continent there is indeed a correlation of latitude and longitude with Neanderthal ancestry, but that correlation is almost entirely the result of the western half of Asian samples.

From this, Di Santo and coworkers draw a map of the extent of interbreeding between the expanding modern human population and the Neanderthals they encountered. That map shows the range of mixture extending from the Levant to Kashmir, northward to the Volga, and westward encompassing most of Europe to the Marne. It’s not much short of the full known geographic range of Neanderthals.

Bottom line

These studies from Mathias Currat’s research group help to put a more decentralized Neanderthal ancestry back on the table. There was not one small, special place where incoming African people and Neanderthals mixed. The mixture happened as a wave.

The clinal pattern of Neanderthal mixture is real, but visible only once you start looking at very large numbers of genomes. With small numbers, the effect is overwhelmed by individual variation.

Equally real is the abbreviated timeline during which mixture seems to have happened. In 2025, two research studies suggested that the Neanderthal ancestry of living people had mostly come in one extended pulse, estimated from 50,000 to 43,000 years ago. These studies have placed an upper limit on the time that some 95% of the genetics of today’s Eurasian people started from a small founder population.

I think these converging lines of research align with a single scenario.

Sometime after 70,000 years ago, a small founder population left its close relatives in North Africa and entered the Levant.

The Basal Eurasians are simply the descendants of these founders nearest the starting line, the lowest end of Neanderthal mixture in the cline.

The uptake of Neanderthal ancestry initially was high, owing to the small size of the founder groups. Some of the Neanderthal gene regions proved to be deleterious in the growing population. But other variants were adaptive, adding to the population’s growth potential.

Once a wavefront was established, the groups grew at an intrinsic growth rate of between 2% and 4% per generation. That’s a growth rate comparable to many prehistoric human groups, an order of magnitude slower than many post-industrial human populations.

With a range size and birth-to-marriage distance comparable to human hunter-gatherers, the wave advanced at a velocity of around 20 km per generation. In 7000 years, the wave traveled between 4000 and 6000 km.

At this point, Neanderthals remained in small pockets at the ends of their former range, and nearly all remaining descendants of the Neanderthals were modern people with between 1% and 4% Neanderthal ancestry.

A fast wave of advance is a good match to the skeletal record. The people from sites like Bacho Kiro, Bulgaria, and Ranis, Germany, arrived in Europe within a few thousand years after the founder group started to expand.

The earliest Neanderthals to mix into this expanding population were from Southwest Asia, making up a disproportionately high fraction of the ultimate Neanderthal genomic legacy. The Neanderthals that lived further toward Europe and Central Asia may have been fewer in number and lower in density. But the main reason they had less genetic impact was simply the uninterrupted growth of the newcomers.

Still, the cline of Neanderthal ancestry shows that their integration at the frontier of modern human expansion was a common occurrence, having a persistent effect on the variation of their descendant populations.

Looking at today’s people, more than 1500 generations have passed since any Neanderthal ancestors lived, fragmenting great introgressed blocks of chromosomes into much shorter shards of sequence. Geneticists can amplify the weak signal from living people’s genomes by building up samples of many thousands of participants. The remarkable thing about ancient genomes is that they now number in the thousands, too. That is changing the way we can look at these critical events in our evolutionary history.

References

Di Santo, L. N., Quilodrán, C. S., Cerrito, P., & Currat, M. (2026). Tracing the Neanderthal–Modern Human hybrid zone using paleogenomic data. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.64898/2026.01.06.697899

Fu, Q., Hajdinjak, M., Moldovan, O. T., Constantin, S., Mallick, S., Skoglund, P., Patterson, N., Rohland, N., Lazaridis, I., Nickel, B., Viola, B., Prüfer, K., Meyer, M., Kelso, J., Reich, D., & Pääbo, S. (2015). An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature, 524(7564), 216–219. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14558

Iasi, L. N. M., Chintalapati, M., Skov, L., Mesa, A. B., Hajdinjak, M., Peter, B. M., & Moorjani, P. (2024). Neanderthal ancestry through time: Insights from genomes of ancient and present-day humans. Science, 386(6727), eadq3010. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq3010

Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Mittnik, A., Renaud, G., Mallick, S., Kirsanow, K., Sudmant, P. H., Schraiber, J. G., Castellano, S., Lipson, M., Berger, B., Economou, C., Bollongino, R., Fu, Q., Bos, K. I., Nordenfelt, S., Li, H., de Filippo, C., Prüfer, K., … Krause, J. (2014). Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature, 513(7518), 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13673

Quilodrán, C. S., Rio, J., Tsoupas, A., & Currat, M. (2023). Past human expansions shaped the spatial pattern of Neanderthal ancestry. Science Advances, 9(42), eadg9817. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adg9817

Quilodrán, C. S., Tsoupas, A., & Currat, M. (2020). The Spatial Signature of Introgression After a Biological Invasion With Hybridization. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 569620. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.569620

Sankararaman, S., Patterson, N., Li, H., Pääbo, S., & Reich, D. (2012). The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans. PLoS Genetics, 8(10), e1002947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002947

Sümer, A. P., Rougier, H., Villalba-Mouco, V., Huang, Y., Iasi, L. N. M., Essel, E., Mesa, A. B., Furtwaengler, A., Peyrégne, S., de Filippo, C., Rohrlach, A. B., Pierini, F., Mafessoni, F., Fewlass, H., Zavala, E. I., Mylopotamitaki, D., Bianco, R. A., Schmidt, A., Zorn, J., … Krause, J. (2024). Earliest modern human genomes constrain timing of Neanderthal admixture. Nature, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08420-x

Wall, J. D., Yang, M. A., Jay, F., Kim, S. K., Durand, E. Y., Stevison, L. S., Gignoux, C., Woerner, A., Hammer, M. F., & Slatkin, M. (2013). Higher Levels of Neanderthal Ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans. Genetics, 194(1), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.148213

Yuan, K., Ni, X., Liu, C., Pan, Y., Deng, L., Zhang, R., Gao, Y., Ge, X., Liu, J., Ma, X., Lou, H., Wu, T., & Xu, S. (2021). Refining models of archaic admixture in Eurasia with ArchaicSeeker 2.0. Nature Communications, 12(1), 6232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26503-5

John, I’m puzzled by the apparent 20,000-year gap between 70,000 years ago when early modern humans crossed into southwest Asia and 50,000-to-43,000 years ago when that founder population started interbreeding with Neanderthals in the same region.

Did modern people stay in one relatively confined area without expanding or wandering for 20,000 years? Did they simply not encounter Neanderthals, or did they encounter them without interbreeding?

Or did something change in the modern human population or culture in that 20,000-year period which suddenly caused them to surge out of their once-confined area, start expanding their geographic range and continue to do so on an ongoing basis, and start interbreeding with the Neanderthals (and Denisovans?) they encountered?

Thanks for your provocative series.

One more conclusion one can make from the Neanderthal admixture geographic distribution - refutation of an old myth of the "rapid coastal travel out of Africa". It was never more than a purely mental construct without any archaeological or genetic evidence, but was largely brought to explain early human presence in SEA and Australia.

This myth (and corresponding maps) still fills nearly all anthropological textbooks and museums.

This just never happened.

If early humans settled the Indian ocean coast first and then expanded inland, the geography of Neanderthal introgression would be very different, of course. But data shows that N. admixture in any ancient indigenous people in SEA (including such extremely old isolates as Andamans) is very similar to other Asians. It is clear that modern humans came to SEA from the north (all the way from Siberia), not along the coast. This is also confirmed by a shockingly small genetic distance between Tianyuan man and modern Andamanese, as well as prevalence of old Y-DNA F->K and C lineages in indigenous SEA and Sahul region.