What explains the long stasis of Oldowan sites?

A new study reveals a 300,000 year record of toolmaking near the eastern shore of Lake Turkana

I’ve been fascinated after reading new research from David Braun and collaborators focusing on the early Oldowan tool assemblages from Namorotukunan, north of Ileret, Kenya. The report describes three sites, all located within a radius of around 200 meters from each other, but separated in different geological levels stretching from around 2.75 million to 2.44 million years ago.

Across these 300,000 years, the technology and strategies of the toolmakers appear to have been much the same.

What changed was their environment. Starting from a well-watered floodplain with many trees, the local habitat became drier with less woody cover and more natural fires. Later the spot was inundated by a newly resurgent paleolake. It seems that the toolmakers’ lifestyles tolerated the shifting local resources without needing to change the way they made and used tools.

The limits of archaeology

Now, when it comes to causal connections of climate change and hominin behavior, I am especially alert to the weakness of most data from Paleolithic archaeology. I don’t doubt that changes in climate and local environments were made a difference to our evolution, probably at many times and places. But when it comes to testing changes in behavior over time, even a very rich archaeological site ultimately distills down to a single data point.

In this study, the archaeological data represent three brief intervals out of a 300,000-year span. The study presents strong data that the local environment was not constant across this interval. It is the apparent lack of correlation between archaeology and environmental change that makes the story. Environment changes, hominin behavior didn’t.

I have my doubts about the strength of this conclusion, based as it is upon a lack of evidence of change between small artifact samples.

Even so, I really like the study for many reasons. Every one of the samples of early stone artifacts are small. The Oldowan archaeological sites of this range of ages are incredibly rare: They include a few localities in the Gona field region of Ethiopia, one assemblage described from the Ledi-Geraru area, and the site recently described from Nyayanga, Kenya. So a report like this one adds substantially to the knowledge base.

Namorotukunan

When it comes to archaeology, the work described by Braun and coworkers is a long term study. The researchers spent the period from 2013 to 2022 excavating, collecting information, and analyzing finds from the three distinct sites, designated as NMT1, NMT2, and NMT3—and their surroundings.

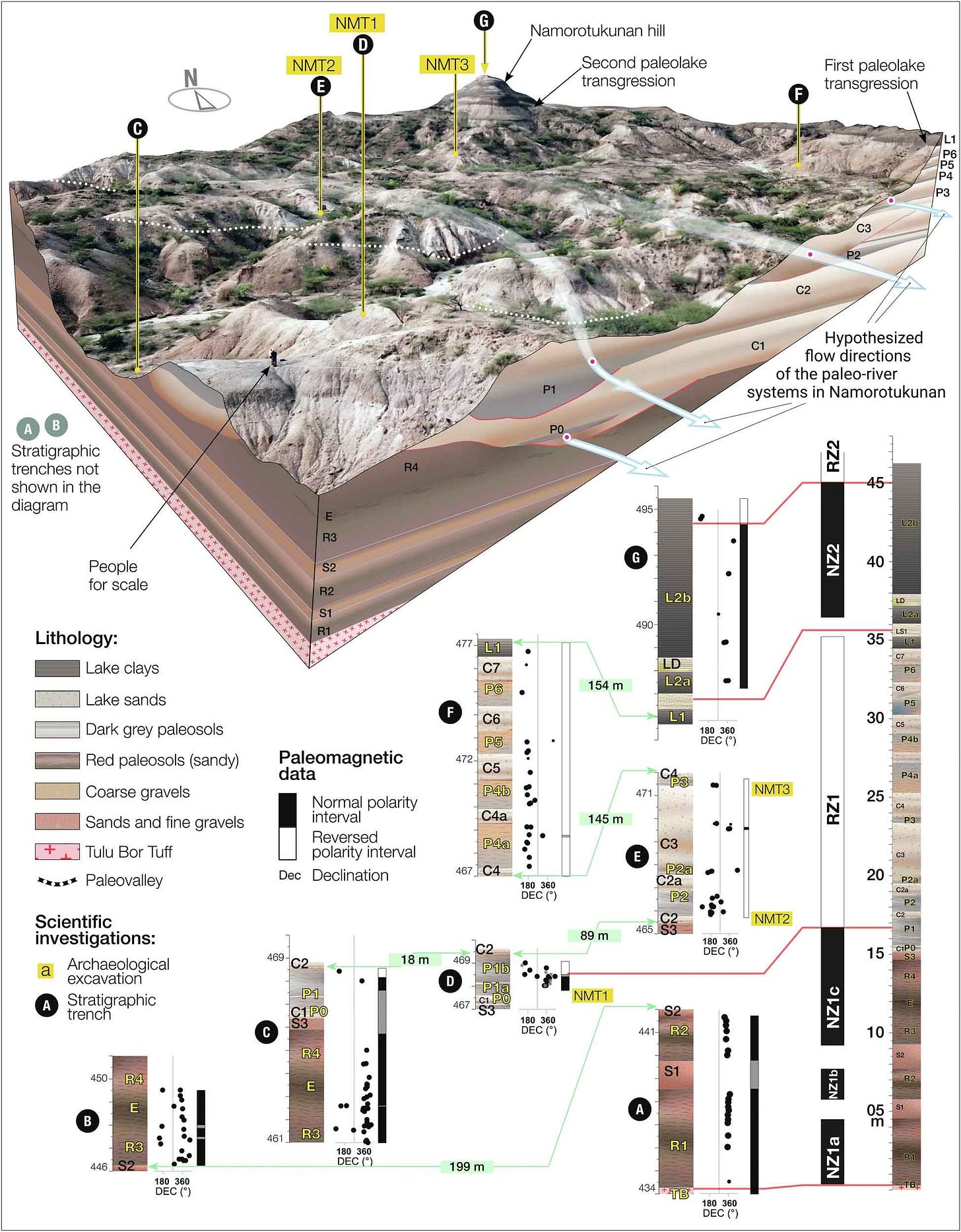

What blows me away about the Namorotukunan work is the extent of geological and environmental evidence that the team has recovered from the area. Their article includes a remarkable three-dimensional rendering of the present-day topography, a reconstruction of the paleoriver network that created many of the sedimentary deposits, and the sequence of changes to sedimentation over time.

It’s really lovely work. These kinds of reconstructions are important not only for the immediate region but for understanding the changes in hydrology across the entire Turkana Basin. If you’re someone who could use a visual understanding of how this kind of ancient site is formed, this is a great one to study.

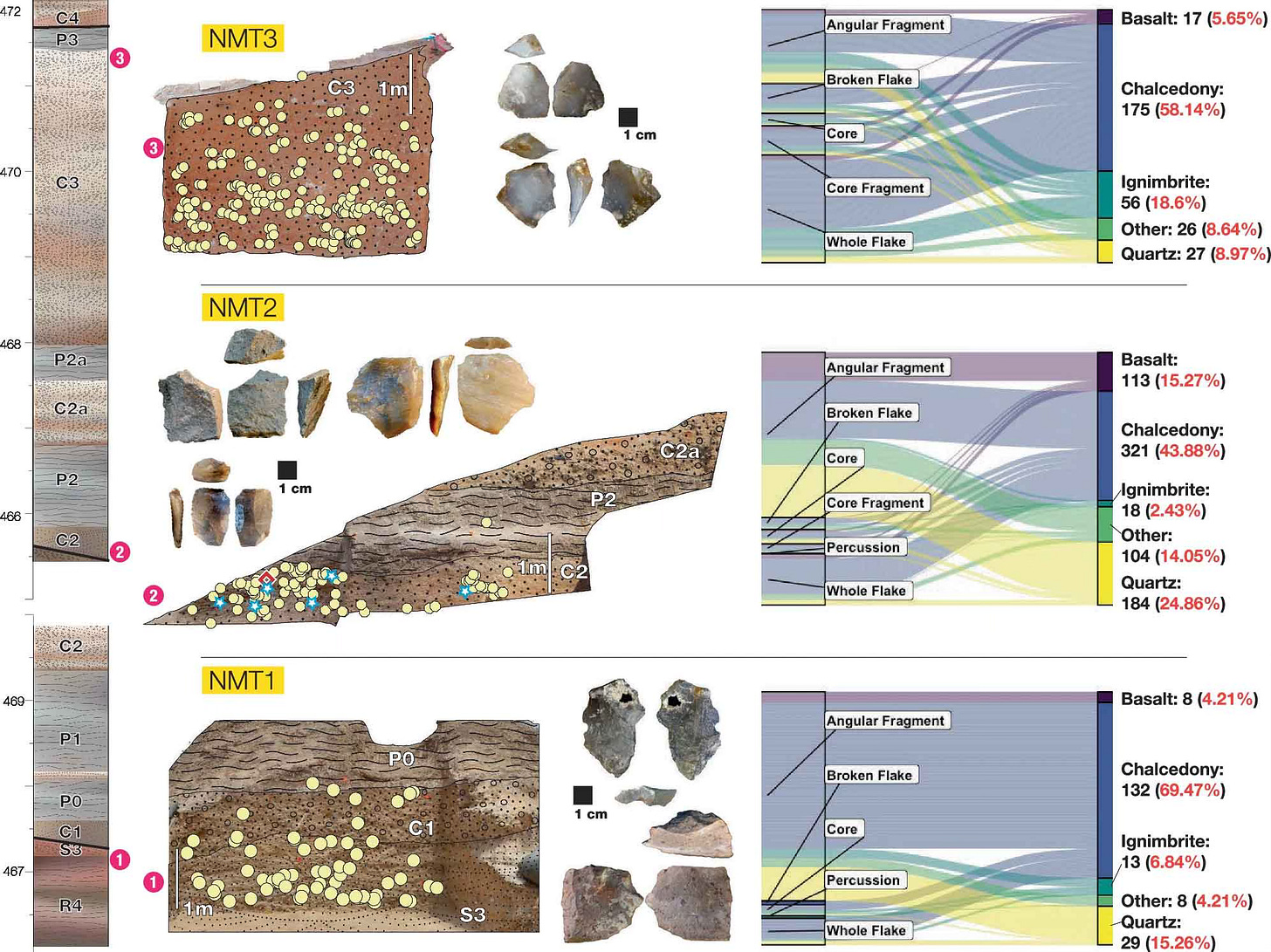

The team recovered 1290 artifacts from the three sites. The richest of the three was the NMT2 site in the middle of the time span at around 2.6 million years ago, which produced a bit more than half of the artifacts. There were no hominin bones in the area, and little preservation of faunal bones in the excavated sites, with only 32 found. Further, only the NMT2 site preserved a few bone surfaces well enough to examine for cutmarks or other traces of hominin activity. The team identified cutmarks on one bone.

The toolmakers chose river-worn cobbles of rock that were abundant within the streambeds of the immediate area. There is no evidence that they transported any pieces of rock any distance further than the nearest stream, within dozens of meters of the sites. Among these, the toolmakers mostly chose chunks of a kind of crypto-crystalline silica known as chalcedony, preferring it over other types of rock for its fracture qualities that give rise easily to sharp flakes. The three sites all show very similar selectivity of this type of rock, and are similarly flake-dominated. And when Braun and collaborators looked at how the flakes were made, they could show similar sequences of rotation of the small cobble cores to remove flakes from them across all three of the sites.

The three sites do present a slight difference in their assemblages. Percussion—pounding rocks, bones, or plant material—is one of the major uses of Oldowan artifacts at most sites. But out of the Namorotukunan sites only NMT2 has artifacts that show evidence of percussion, and only very few at that. Braun and coworkers note that the local cobbles are not rock types that stand up to much pounding, so it’s maybe not surprising they didn’t use them much in this way. But an Oldowan site where nobody pounded anything is an unusual Oldowan site, really suggesting that the hominins were very constrained in their activities by the locally available materials.

Oldowan stability

Why was the Oldowan apparently stable for so long? I don’t think I’m saying anything very profound when I say that what looks like stability is partly an illusion of sampling.

The basis of technical behavior that archaeologists have categorized as “Oldowan” is production of sharp flakes and hammering or pounding with roughly fist-sized rocks. Hominins used the sharp flakes for disarticulating and slicing meat from animal carcasses, and probably for cutting into parts of plants and shaping wood. They pounded animal bones with hammers to get into the marrow-rich medullary cavities, and pounded plant foods including nuts, large seeds, and edible underground parts such as tubers.

Their use of wood is mostly invisible to us today. Wood was essential for digging for underground plant foods and invertebrates, for probing for honey, and for spearing small animals. Chimpanzees do all these things. Our only trace of such activities from archaeology has been close analysis of the surfaces of some stone flakes that suggest they had been used to shape wood.

The Namorotukunan sites tell us that hominins in this place shaped their activities based on the available rock types. That’s very similar to the patterns of behavior shown by stone use among chimpanzees today. Chimpanzees will transport rocks that they use for pounding and cracking nuts over short distances of dozens of meters, and these short trips can add up over time. They have not been observed to intentionally flake stone, and they do not crack nuts everywhere that nuts and suitable rocks both exist.

What would an archaeological perspective look like on any single location over hundreds of thousands of years of chimpanzee presence? Over many generations, chimpanzees that sustain a tradition of nutcracking might disappear from any given area. There might be long absences of chimpanzees altogether, with periods of local environmental unsuitability for them. New chimpanzee groups would sometimes pass through, lacking nutcracking altogether. Their wood and leaf-based technologies would leave no trace. Again later, local chimpanzees might invent nutcracking, or newcomers might bring the technique from elsewhere. Using local rocks, they would leave much the same record.

Archaeologists looking specifically for stone artifacts would find occasional assemblages. They would observe how similar the assemblages look.

Still, there are some differences across space and time that tell us something important about Oldowan toolmakers’ behavioral variation. At some places, Oldowan toolmakers went out of their way to retrieve and transport the stone they preferred, across many kilometers.

Earlier this year, Emma Finestone and collaborators reported on the transport of stone to the site of Nyayanga, in western Kenya near Lake Victoria. This site dates to between 3.03 and 2.58 million years, making it possibly the earliest Oldowan site, depending on its exact position in that range of ages. The transport of stone over such distances is something chimpanzees do not do; it shows that these Oldowan toolmakers had larger geographic ranges and knowledge of resources across space.

The Namorotukunan evidence fits together with most other early Oldowan sites, including Hadar, Gona, and Ledi-Geraru. Long-distance transport of stone does not appear to have been typical for early Oldowan toolmakers. Such a site may show the potential for invention. But demonstrating regional and temporal variability will require many more data points. With more sites, archaeologists will begin to have the kind of samples that might test correlations with environmental or climatic data.

Reference

Braun, D. R., Aldeias, V., Archer, W., Arrowsmith, J. R., Baraki, N., Campisano, C. J., Deino, A. L., DiMaggio, E. N., Dupont-Nivet, G., Engda, B., Feary, D. A., Garello, D. I., Kerfelew, Z., McPherron, S. P., Patterson, D. B., Reeves, J. S., Thompson, J. C., & Reed, K. E. (2019). Earliest known Oldowan artifacts at >2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, highlight early technological diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(24), 11712–11717. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820177116

Braun, D. R., Palcu Rolier, D. V., Advokaat, E. L., Archer, W., Baraki, N. G., Biernat, M. D., Beaudoin, E., Behrensmeyer, A. K., Bobe, R., Elmes, K., Forrest, F., Hammond, A. S., Jovane, L., Kinyanjui, R. N., de Martini, A. P., Mason, P. R. D., McGrosky, A., Munga, J., Ndiema, E. K., … Carvalho, S. (2025). Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya. Nature Communications, 16(1), 9401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x

Finestone, E. M., Plummer, T. W., Ditchfield, P. W., Reeves, J. S., Braun, D. R., Bartilol, S. K., Rotich, N. K., Bishop, L. C., Oliver, J. S., Kinyanjui, R. N., Petraglia, M. D., Breeze, P. S., Lemorini, C., Caricola, I., Obondo, P. O., & Potts, R. (2025). Selective use of distant stone resources by the earliest Oldowan toolmakers. Science Advances, 11(33), eadu5838. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adu5838

Plummer, T. W., Oliver, J. S., Finestone, E. M., Ditchfield, P. W., Bishop, L. C., Blumenthal, S. A., Lemorini, C., Caricola, I., Bailey, S. E., Herries, A. I. R., Parkinson, J. A., Whitfield, E., Hertel, F., Kinyanjui, R. N., Vincent, T. H., Li, Y., Louys, J., Frost, S. R., Braun, D. R., … Potts, R. (2023). Expanded geographic distribution and dietary strategies of the earliest Oldowan hominins and Paranthropus. Science, 379(6632), 561–566. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo7452