What the heck are chins for?

A human characteristic that remains an enduring evolutionary enigma.

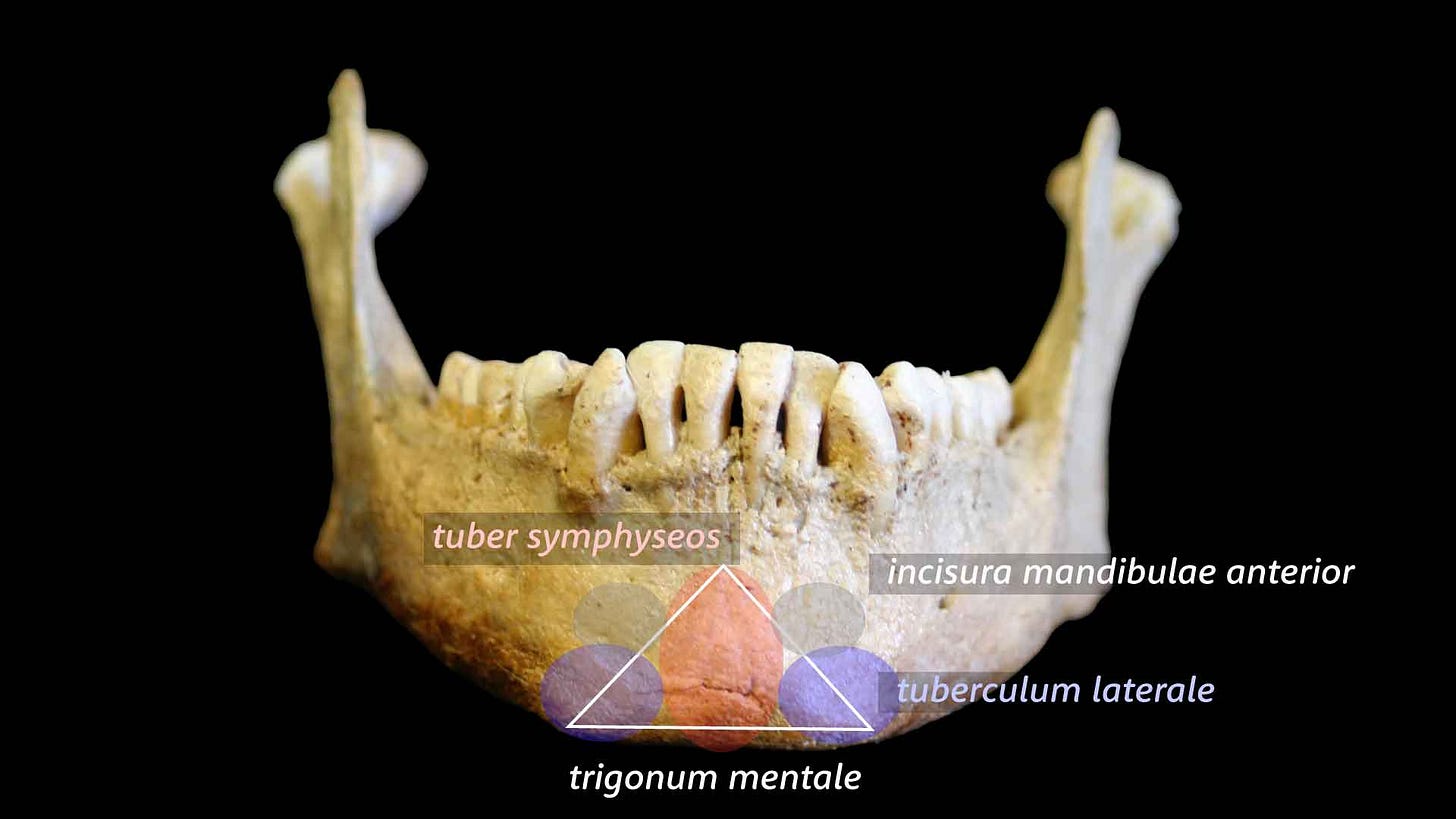

The human chin is a quirk of evolution. In everyday language, a chin is just the front of the jaw below the mouth. But to bone specialists, a chin is a very particular piece of mandibular real estate. The anatomical chin is a thickened projection of the anterior surface of the mandible, usually forming a triangle or “T” shape, below the sockets that hold the incisor and canine roots.

From at least the eighteenth century—before anthropologists even existed—writers including Linnaeus and Blumenbach accepted that a chin is a unique feature of the human jaw, not seen in other kinds of mammals. The anatomist W. D. Wallis, who wrote about the human chin back in 1917, took the idea back to Pliny the Elder who mentioned the unique nature of the human chin in his Natural History during the first century CE.

“The Greeks when in the act of supplication, touched the chin to show, as some would say, their affinity with the divine, and, if this is true, making fitting recognition of its human peculiarity as a trait not shared by the animals. But no Greek scientist seems to have speculated about its origin.”—W. D. Wallis

By the early twentieth century, the growing fossil record showed that the chin was a fairly recent innovation in human evolution. Extinct human relatives tended to lack a projecting chin of any kind. The Mauer mandible attributed to Homo heidelbergensis was a prominent example, as was the La Naulette, La Chapelle-aux-Saints, and the Krapina series of Neanderthal mandibles. The mandibular symphysis of these fossils—where the two halves of the mandible meet—is as thick or thicker than in most living people. But the symphysis angles from the incisors back, sometimes more strongly buttressed on the internal surface instead of an external chin.

But why? Where every other species of primate has a mandibular symphysis running down and backward from the teeth, why does the human symphysis bulge forward?

Over the years, anatomists and biologists proposed a half-dozen ideas. A few were wacky from the start, “just-so stories” that seem hardly testable.

Some imagined that the evolution of human language required a larger oral cavity in humans than other primates. With natural selection trying to give the tongue more room to work, the bony reinforcement of the mandibular symphysis had to move to the outside.

This chin-wagging notion led the twenty-sixth U.S. President to further a stereotype about Homo heidelbergensis:

“He was a chinless being, whose jaw was still so primitive that it must have made his speech imperfect; and he was so much lower than any existing savage as to be at least specifically distinct—that is, he can be called ‘human’ only if the word is used with a certain largeness.”—Theodore Roosevelt

Today, anthropologists often mention the idea that language might somehow be related to the chin’s evolution. The most common version of this idea is that speech constrains the placement of the tongue and musculature connected to the hyoid bone and the base of the mandible. The teeth and face became smaller in recent human evolution, but the mandibular base could not follow.

The idea is appealing on its surface, but struggles with a basic fact of human development: Children learn to speak with oral cavities vastly smaller than most adults.

Another idea was that the chin might provide support for human facial expressions by anchoring the lip and lower face musculature. Because the larger muscles of facial expression do not have attachments on the chin itself, this idea leans on smaller muscles—especially mentalis, which originates just above the chin and tends to protrude the lower lip and wrinkle the skin.

An interesting angle on the chin’s relation to facial expressions is attributable to Charles Darwin. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, he noted that human facial expressions related to sadness look uniquely different in humans compared to other primates. The reason is simply the shape of the human chin, which shifts the soft tissue’s movement. The structure of the face not only anchors the muscles of expression, but is also the stage upon which they play.

A chin is an important part of what makes a face memorable. This underlies a third hypothesis for the chin’s function: sexual selection. The most common version of this hypothesis is that female adults tend to choose mates that have broader and more prominent chins.

Male and female adult humans all have chins, of course. Most sexual signals evolve to be unambiguous. The male pattern of facial hair, including a beard on the chin, makes for a pretty clear signal. The bone underlying all of that is hardly visible.

Still, chins of male individuals tend to be broader with well-developed lateral tubercles, and they protrude forward more. Chins of female individuals are generally narrower and less protruding. It’s this sexual dimorphism that some researchers have highlighted as support for the idea of sexual selection. Sometimes a structure that first appeared for some other reason gets co-opted as a signal. Some have suggested that the broad male chin is a signal correlated with testosterone, others that the narrow female chin is a signal of estrogen. Neither has been confirmed with physiological data.

Zaneta Thayer and Seth Dobson in a 2013 study observed that populations of humans from different parts of the world have different chin morphology. If mate preference is part of the explanation for their mandibular form, cultures seem to have different tastes. This variability detracts from the idea that a mating preference universal to Homo sapiens might explain why human jaws are differently shaped from our evolutionary ancestors.

The variation among recent human populations in chin form suggests humans are less distinctive than Pliny imagined. Some fossil jaws usually attributed to archaic groups, especially among the Neanderthals, also project slightly at the symphysis, or have raised relief overlapping with modern people.

My first encounters with fossil chins in the 1990s were at a time when researchers hotly debated the meaning of this overlap. Many researchers maintained that any resemblances between modern and archaic chins were purely superficial. The most well-known breakdown was written by Jeffrey Schwartz and Ian Tattersall. They emphasized that the details of chin shape matter. A central, raised keel along the midline, known in anatomy as the tuber symphyseos, and a pair of broadly spaced bumps on the mandibular base, tubercula lateralia, combine to make a triangular or T-shaped structure. Find the inverted T and you find a modern human.

My view was that if chins blurred the line between Neanderthal and modern, probably the line is illusory. With today’s genetic data it’s clear that ancient populations belonged to a network of genetic exchanges. Mandibular form is just one of many areas of overlap.

A similar point of view can be found in a 2002 study by Seth Dobson and Erik Trinkaus. They recognized that some earlier humans had faint traces anticipating parts of the modern human chin. On a receding mandibular symphysis, such as the massive million-year-old Tighènif 3 jaw, a trace of a tuber symphyseos may be unexceptional. But in a more vertically-oriented symphysis like the Amud 1 Neanderthal, a slight bulging at the mandibular base becomes clearer. If such discrete elements of the chin were already present in archaic humans, then expanding these elements and reducing alveolar portion of the mandible brings them into a modern configuration. Maybe all that was needed was a push.

But was that push functional, or was it evolutionary happenstance?

Out of all the ideas about the evolution of the chin, two have occupied the most attention over the last few decades. One idea holds that the chin is an external buttress, helping human jaws to minimize bending strain at the mandibular symphysis. The other holds that the chin is a spandrel: a trait that evolved as a by-product of selection for some other trait.

The functional perspective is tied to the deeper evolutionary history of hominins. Many early human relatives had truly massive jaws and teeth. Paranthropus boisei, with molar teeth four times the size of today’s people, is the most extreme of these fossil species, but even species like Australopithecus afarensis outclassed chimpanzees and humans in jaw thickness, mandibular height, and molar and premolar sizes.

The branch that led first to Homo and later to modern humans tended to reduce tooth and jaw sizes at every step. With temporalis and masseter muscles pulling from the larger-brained human skull, and with shorter tooth rows relative to the palate’s width, the geometry of the human bite tends to create a wishbone effect at the middle of the jaw.

Dobson and Trinkaus looked at the mandibles of modern humans and Neanderthals to understand what difference a chin might make to mandibular function. For mandibles of similar size, they found that a chin is irrelevant to the mandible’s resistance to bending strain. In a later study, James Pampush and David Daegling pointed out that extending the mandible further forward tends to increase the wishboning effect, not decrease it. A chin doesn’t reduce strain; it makes matters worse.

The spandrel idea reaches deep into evolutionary biology. Louis Bolk was a Dutch anatomist of the early twentieth century, who observed that human adults retain some of the form seen in babies of other primate species, such as high, curved foreheads and small faces tucked beneath the front of the cranial vault. He considered such neoteny—retention of juvenile traits—as a result of an evolutionary process he termed fetalization. Bolk saw this as an intrinsic organizing principle of human evolution.

The chin, Bolk thought, came from a developmental slowdown of the part of the jaw that holds the teeth. The basal part of the mandible was left protruding beyond it.

A similar view had been proposed by Franz Weidenreich, who much later played an important role in analysis of the Homo erectus “Peking Man” fossils from Zhoukoudian, China.

“Weidenreich viewed the progressive development of the chin as purely a passive process: it got ahead by remaining where it was, the superior alveolar region being meanwhile in retreat.”—W. D. Wallis

Stephen Jay Gould drew attention to the legacy of this idea in his 1977 book, Ontogeny and Phylogeny. One of Gould’s aims was to revive the old idea of neoteny in human evolution. But in the chin he perceived a challenge. Neoteny is an arrestation of growth. The human face fails to grow forward into the larger snout of other apes, holding the pattern of youth. The chin protrudes more than in any ape. It is not an arrestation, it’s an addition.

Gould squared the chin’s circle by taking a page from Weidenreich and Bolk. The chin did slow down, Gould wrote. It just slowed down less than the part of the mandible that holds the teeth.

But clever as it is, this idea begs the real question. If the chin is explained by a differential slowdown of mandibular growth, why did the two parts of the mandible slow down differently?

During the last ten years, research on the mandible has focused on this question by trying to understand the modularity of jaw development. As the body grows, different parts are affected by regulatory programs that are to some extent integrated across parts of the body. When parts must function in tandem with each other, natural selection tends to maintain an integration of their development.

The alveolar portion of the mandible is a prime example. The lower teeth must work in tandem with the upper teeth. If they developed at different rates or became very different sizes, normal chewing might become difficult or impossible. The strength of developmental integration of the maxilla and alveolar portion of the mandible keeps such mismatches from happening.

Weaker is the integration between the basal portion and alveolar portion of the mandible. The differences in pacing of these portions suggest that they are affected by distinct patterns of gene regulation.

A recent study by Noreen van Cramon-Taubadel and coworkers worked toward an understanding of the pattern of selection on the various parts of the mandible. They examined mandibular variation and evolution across great apes and humans, finding that aspects related to the chin in living humans show varying patterns of selection across the apes. Their work aligns with earlier studies led by James Pampush, which followed the evolution of a more vertical symphysis and shorter mandible across hominins. A centerpiece of these studies is that the features that make up the modern human chin were subject to selection, but not fully integrated with each other. Nor are they integrated with the longer-term reduction of human jaw length and tooth size.

The story emerging from this work is that the chin is indeed a by-product of competing demands on mandibular shape and size. One part of the story was clearly the developmental requirements of smaller teeth and the resulting evolution of a shorter face.

The other part of the story traces far before birth. Just as the brain expands rapidly before birth, the chin adopts the inverted T shape as early as the 11th week of gestation. Studies led by Michael Coquerelle may show why this is a structural necessity. As a fetus develops, it begins swallowing and breathing amniotic fluid—vital exercises for building the lungs and digestive tract. But human anatomy poses a challenge: our upright posture places the spine and neck in a way that constricts the throat. To prevent the airway from collapsing and to give the tongue and throat room to work, the bottom of the jaw must grow faster than the top.

The adult shape of the chin may have been misleading anatomists all along. This helps make sense of the diversity in the shape and size of components of the chin across human populations. Even the trends in many populations toward loss or malocclusion of wisdom teeth—strongly affecting the alveolar portion of the jaw—seem not to have been correlated with changes to the chin. After the first years of life, the structure has been free to vary independently of changes in tooth size and function. In extinct populations of humans, like the Neanderthals, larger teeth and more projecting faces prevented the fetal mismatch from occurring.

The bottom line for evolution is not how we divide the body into parts, but instead how structure matters to survival or reproduction. From Pliny’s time, naturalists have had no shortage of ideas for why a chin matters. Studies of development have helped advance our understanding of how traits are correlated with each other and with survival across the lifespan, even in the earliest phases of development.

Notes: Any subject with as long a history as the study of mandibular evolution is hard to summarize in a reasonable length. The developmental biology of this feature has occupied anatomists since well before Bolk’s time, and continued on along several avenues. Another interesting sideline that matters for studies of fossils is the challenge of defining what is meant by a chin. I mentioned the work of Schwartz and Tattersall in the post, and for readers who would like to follow up more on that aspect, I recommend the recent article by Andra Meneganzin and coworkers.

References

Bolk, L. (1924). The chin problem. Verslagen van de Akademie Wetenschapen Amsterdam, 27, 329-344.

Coquerelle, M., Prados-Frutos, J. C., Rojo, R., Drake, A. G., Murillo-Gonzalez, J. A., & Mitteroecker, P. (2017). The Fetal Origin of the Human Chin. Evolutionary Biology, 44(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-017-9408-9

Dobson, S. D., & Trinkaus, E. (2002). Cross-sectional geometry and morphology of the mandibular symphysis in Middle and Late Pleistocene Homo. Journal of Human Evolution, 43(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2002.0563

Meneganzin, A., Ramsey, G., & DiFrisco, J. (2024). What is a trait? Lessons from the human chin. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution, 342(2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.23249

Pampush, J. D. (2015). Selection played a role in the evolution of the human chin. Journal of Human Evolution, 82, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.02.005

Pampush, J. D., & Daegling, D. J. (2016). The enduring puzzle of the human chin. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 25(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21471

Pampush, J. D., Scott, J. E., Robinson, C. A., & Delezene, L. K. (2018). Oblique human symphyseal angle is associated with an evolutionary rate-shift early in the hominin clade. Journal of Human Evolution, 123, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.06.006

Roosevelt, T. (1916). How old is man? National Geographic 29(2), 111-116.

Schwartz, J. H., & Tattersall, I. (2000). The human chin revisited: What is it and who has it? Journal of Human Evolution, 38(3), 367–409. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1999.0339

Thayer, Z. M., & Dobson, S. D. (2010). Sexual dimorphism in chin shape: Implications for adaptive hypotheses. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 143(3), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21330

Thayer, Z. M., & Dobson, S. D. (2013). Geographic Variation in Chin Shape Challenges the Universal Facial Attractiveness Hypothesis. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e60681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060681

Verhulst, J. (1994). Speech and the retardation of the human mandible: A Bolkian view. Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 17(3), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/1061-7361(94)90014-0

Von Cramon-Taubadel, N., Scott, J. E., Robinson, C. A., & Schroeder, L. (2026). Is the human chin a spandrel? Insights from an evolutionary analysis of ape craniomandibular form. PLOS One, 21(1), e0340278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0340278

Wallis, W. D. (1917). The development of the human chin. The Anatomical Record, 12(2), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1090120212

White, T. D. (1977). The anterior mandibular corpus of early African Hominidae: Functional significance of shape and size [PhD, University of Michigan]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/302839985