A possible archaic human from Borneo

The find of a single tooth from Gua Danang may be the first evidence of the archaic inhabitants of the island.

Niah National Park is a striking area within the state of Sarawak, part of the nation of Malaysia that is located on the island of Borneo. The park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, known for its massive limestone cave system—particularly the Great Cave, Gua Niah, home to innumerable small birds known as swiftlets. The birds build their nests on the cave walls from hardened saliva, which people harvest and sell to traders, eventually to become the famous “bird’s nest soup”.

People have used these caves for many thousands of years. Work by archaeologists in the west mouth of the cave starting in the 1950s tells some of the stories of the ancient people. Early in the Holocene, rainforest people buried their dead in Gua Niah, placing them in varied positions, flexed, seated, sometimes mutilating the bodies, and often coupling fire with the burials. Later, between 3500 and 2000 years ago were more than 200 burials in the cave, pottery, stone tools, and metal showing connections with broader cultures across the region.

In another cave, Gua Kain Hitam or the “Painted Cave”, a long mural painted from hematite shows boat-shaped coffins on a journey carrying the souls of the deceased. Burials in that cave include remains of coffins like those pictured, dating to within the last 2000 years.

My interests go quite a bit older.

I’m writing about the Niah Caves today because of new work from Darren Curnoe and collaborators, who may have recovered the first fossil evidence of archaic people from Borneo. This comes from Gua Danang, “Trader’s Cave”, named for the bird’s nest traders who used the cave in recent times.

Gua Danang

Like Gua Niah, this smaller cave was also investigated starting in the 1950s. Tom and Barbara Harrisson, who uncovered so much in the larger cave, found little here. The newer round of excavation work took place from 2017 to 2019, with teams under the leadership of the Australian archaeologist Darren Curnoe. They found more.

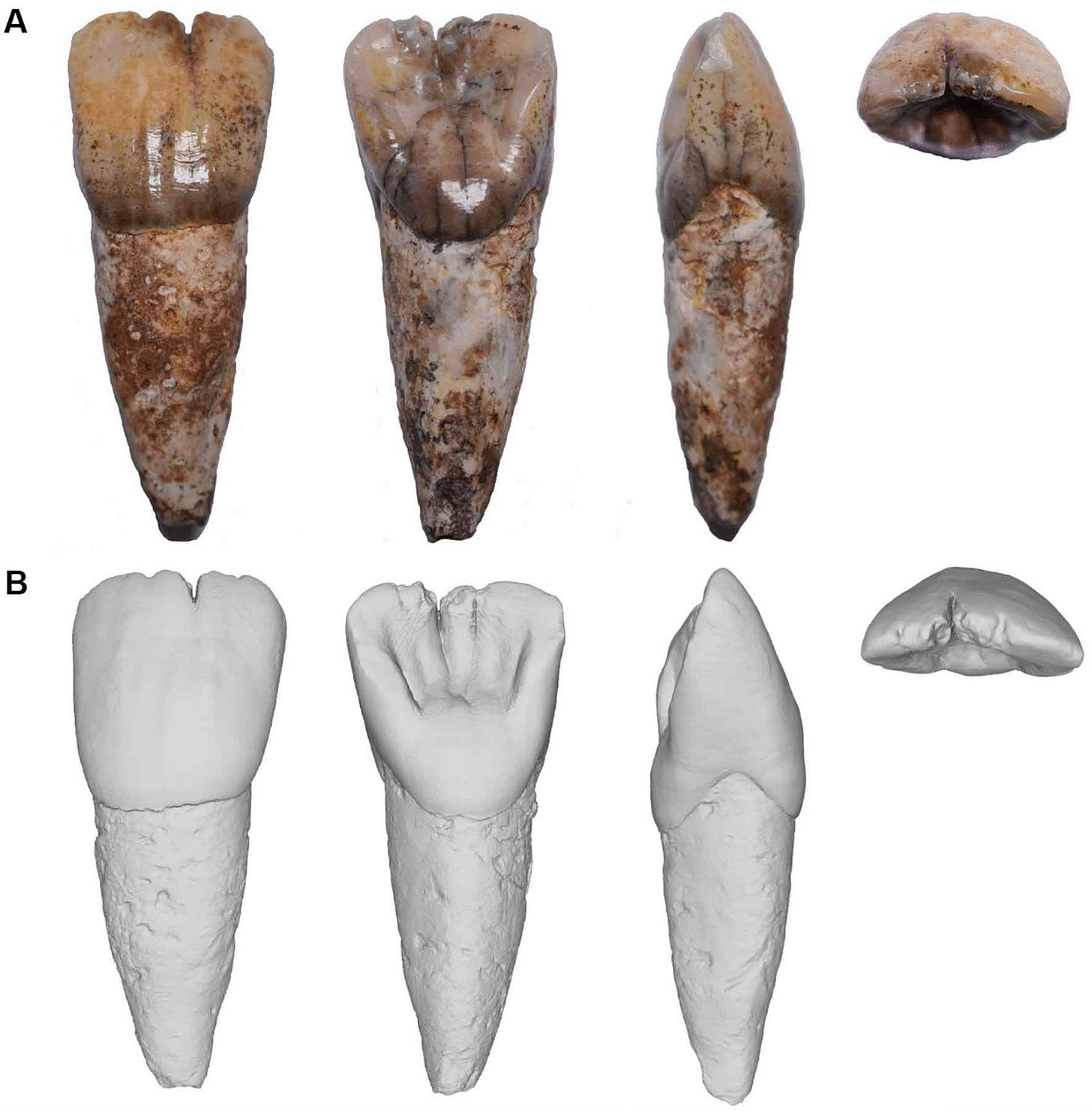

The first report of their work is a new article in PLoS ONE, covering the discovery of a single hominin incisor. I don’t often focus on publications that describe a single tooth. But sometimes discoveries of this kind can shed new light on old questions. This is one of them.

Borneo is one of the biggest question marks on the map of human occupation for most of the Pleistocene. The island was connected to the Asian mainland during periods of low sea level, just like its smaller neighbors Java and Sumatra. Java was home to populations of Homo erectus from at least 1.5 million years ago right through the Middle Pleistocene. By contrast, Borneo and Sumatra have hardly any evidence of human occupation across this time period.

That makes each find very interesting.

In the case of the Gua Danang tooth, AA210, its size would be quite big for a modern human and fits into the range of Neanderthals and other archaic people of mainland Eurasia. Only a few upper central incisors are known from Pleistocene sites on Java, and the AA210 tooth measurements fit within their range of variation. All are much smaller than orangutan central incisors, so Curnoe and coworkers rule out that possibility.

The incisor crown is rounded on its front surface—known as “labial convexity”—and it has ridges on both its mesial and distal edges. This shoveled shape, combined with the labial convexity, is more or less what a Neanderthal incisor looks like. Its shape a bit more convex than most of the archaic human teeth from mainland East Asia, although I wouldn’t consider the convexity to be a very strong indication of relationships.

Curnoe and coworkers report OSL ages for the stratigraphic layers in Gua Danang, with the tooth coming from a layer that has an age estimate of 54 ± 5 ka.

The range of 59,000 to 49,000 years is very interesting in light of the finds from nearby Gua Niah. Beneath the early Holocene burials in that cave are much older finds, going back to as early as 46,000 years ago. Until now, these were the earliest hominin finds from Borneo, leading up to the skeletal remains that include the so-called “Deep Skull”.

The Deep Skull

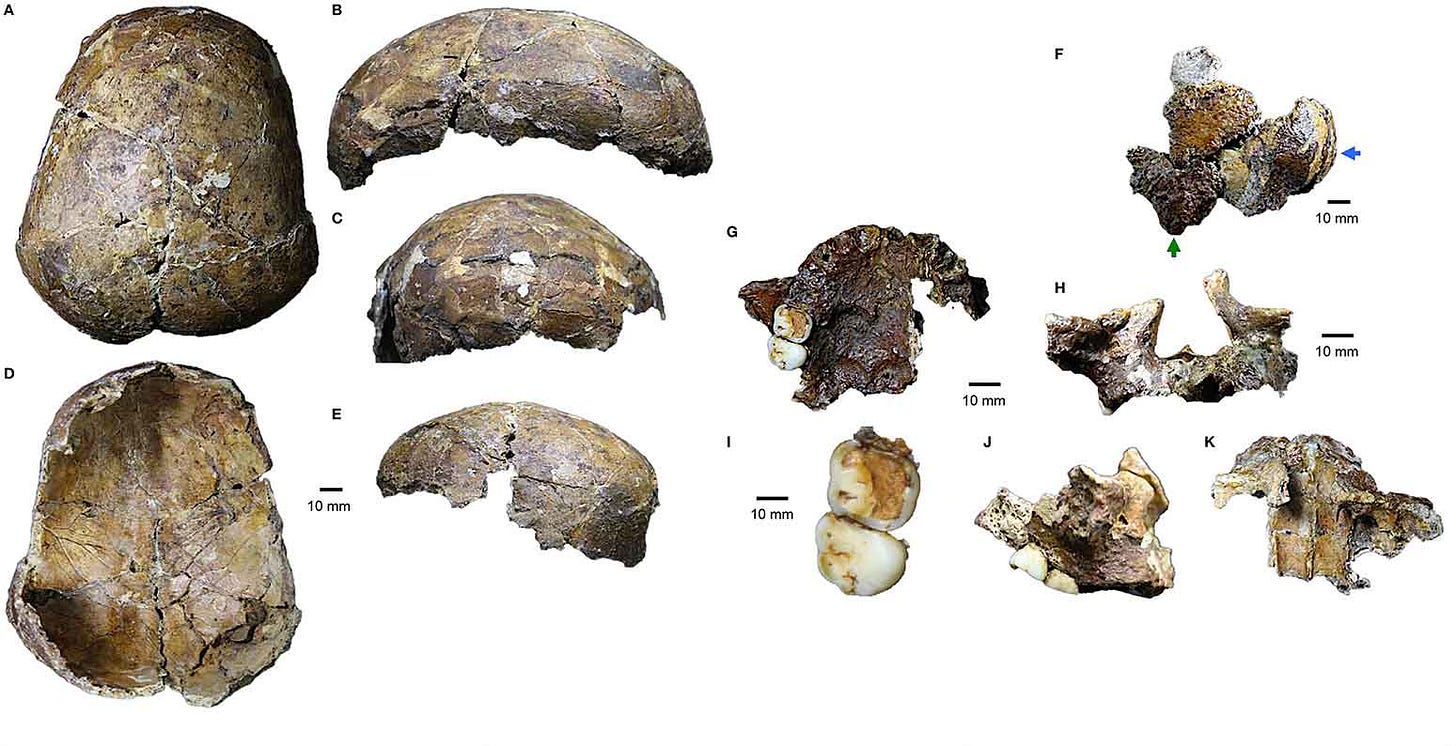

Barbara Harrisson directed excavations in 1957 and 1958 that uncovered a fragmented human cranium. This became known as the Deep Skull from its location nearly 3 meters beneath the present cave floor. A few postcranial bones, including a femur, were also recovered from these excavations. It’s not clear whether these all represent a single individual, although some may, and the femur in particular was recovered close to the Deep Skull.

At the time of their discovery the Deep Skull was thought to be around 40,000 years old. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, this context was revisited in new excavations led by Graeme Barker. A new regime of dating results suggested that the skull comes from between 40,000 and 34,000 years ago. Barker’s work suggests that cultural finds from Niah go back another 5000 or more years earlier than the Deep Skull’s lifetime, back to around 46,000 years ago.

Anthropologists have given this material a great deal of attention for clues about the dispersal of modern humans into the region. The best current idea of early habitation of Australia goes back to 50,000 years or earlier. Modern humans are in evidence at Tam Pa Ling, Laos, by a date of 65,000 years ago. In that context the Niah dates are not so early. But as I’ve written over the last year, the pattern of Neanderthal genetic introgression shared by today’s peoples of the region suggests that their common ancestors came to the area only after 46,000 years ago. Some sites with earlier dates may represent different peoples; some may potentially be in error.

The overwhelming fact is that there are very few human fossils pinning down the pattern of dispersal. Every additional fossil will help. Still, being able to test ideas about these movements will require much more data.

Naturally today everyone loves to see DNA evidence from skeletal remains, me included. Investigation of the Deep Skull for potential radiocarbon dating found no collagen preservation, and that would suggest that DNA preservation is also unlikely.

The morphology of the skull and femur provide some hints about their connections to other populations. These come from a small-bodied person or people, similar in body size and build to some of the island peoples of historic times, such as the Aeta from Luzon. Populations with small body size emerged very quickly in both island and mainland regions of Southeast Asia, from the Andaman Islands to the Philippines.

In their work, Barker and coworkers observe that the Niah people of this time foraged a wide range of rainforest plants, trapped small mammals, fished, and likely practiced deliberate forest burns. These all speak to the kind of effective cultural adaptation to forest life that has been observed in early contexts in mainland Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka.

Bottom line

In the new article on the Gua Danang work, Curnoe and collaborators limit themselves to the description of the hominin incisor and its context. But they mention that the excavations uncovered many stone artifacts that are currently under study. These may help provide a better understanding of the lifeways of the archaic people.

“Further research should provide more evidence about the culture and economic activities of the archaic hominins that occupied the Trader’s Cave and will hopefully shed further light on their identity and the circumstances surrounding their disappearance.”—Darren Curnoe and coworkers

I’ll be very interested to learn whether the Gua Danang evidence shows a similar adaptation to rainforest resources as that suggested by Barker and coworkers for the Deep Skull and its population.

The natural questions that readers will have: Was this Gua Danang tooth Denisovan? Was it the last-surviving Homo erectus? Was it something we haven’t seen yet?

When stone tools are found in a new and unexpected context, we might never make more than an educated guess about who made them. The publication earlier this year of stone tools from Sulawesi more than one million years ago present that challenge. An educated guess is that Sulawesi was likely first inhabited by descendants of Homo erectus similar to those from Java. But until archaeologists find their fossil remains, we won’t know whether these people stayed connected to the larger Sundaland populations, whether they had evolved into something new, or whether they might indeed have come from an unexpected source.

With a hominin fossil, there is at least the chance of something more than a guess. True, the skeletal remains with the Deep Skull may not have preserved DNA. But protein data are another story. Researchers have begun to succeed in protein recovery from teeth of this age and older from East Asia, including the Penghu mandible from the Taiwan Strait. Protein data are much more limited than DNA yet may provide a clue about the relationship of this tooth to other populations.

If I had to bet, I’d guess Denisovan. This site may become one of the keys to understanding the interactions of early modern people with this earlier group.

References

Barker, G., Barton, H., Bird, M., Daly, P., Datan, I., Dykes, A., Farr, L., Gilbertson, D., Harrisson, B., Hunt, C., Higham, T., Kealhofer, L., Krigbaum, J., Lewis, H., McLaren, S., Paz, V., Pike, A., Piper, P., Pyatt, B., … Turney, C. (2007). The ‘human revolution’ in lowland tropical Southeast Asia: The antiquity and behavior of anatomically modern humans at Niah Cave (Sarawak, Borneo). Journal of Human Evolution, 52(3), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.011

Curnoe, D., Datan, I., Goh, H. M., Bin Sauffi, Moh. S., & Ruff, C. B. (2021). Further analyses of the Deep Skull femur from Niah Caves, Malaysia. Journal of Human Evolution, 161, 103089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.103089

Curnoe, D., Datan, I., Taçon, P. S. C., Leh Moi Ung, C., & Sauffi, M. S. (2016). Deep Skull from Niah Cave and the Pleistocene Peopling of Southeast Asia. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2016.00075

Curnoe, D., Sauffi, M. S., Goh, H. M., Sun, X., & Peiris, R. (2025). A Late Pleistocene archaic human tooth from Gua Dagang (Trader’s Cave), Niah national park, Sarawak (Malaysia). PLOS One, 20(12), e0338786. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0338786

Krigbaum, J., & Datan, I. (2005). The Deep Skull and associated human remains from Niah Cave. In J. Majid (Ed.), The Perak Man and Other Prehistoric Skeletons of Malaysia (pp. 131–154). Universitisains Malaysia.

Lloyd-Smith, L. (2014). Early Holocene burial practice at Niah Cave, Sarawak. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 32(0), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.7152/jipa.v32i0.12844

Thank you for this interesting post! Yes, it would be very nice to get proteomic and/or DNA results from the tooth.

A technical question: Is it naive to assess the MD vs LL 2D plot as one would evaluate a PC1 vs PC2 statistically-generated graph?

It seems that this month has been one of numerous interesting publications. I hope you can spare the time from your own work to comment on some other publications (i.e. Sahul migration routes/timing from (primarily) mitogenomes, and the Dmanisi teeth analyses' new species declaration).

Thanks also for a great year of posts!

Interesting! Early settlement of Sahul is one of the most mysterious topics in paleo anthropology, with data contradicting established models. I think the most frustrating contradiction are:

1. genetic data - Neanderthal admixture is similar to other Asians, Y-chromosomes are mostly K lineages, as well as C1b2, and these are associated with “northern” initial UP migrations (probably Altai, Siberia, Tianyuan, and south from that), no IJGH lineage which looks more “southern”. So this must be after 45 ky.

2. Yet there are too many signs of early human presence way before 45ky: Tam Pa Lin, Lida Ajer, maybe Callao, probably this new tooth. Plus archaeological sites in Australia like Madjedbebe. They can’t all be wrong. Plus on genetic side a big difference in coalescence time with Africans, compared to other Eurasians, even after filtering out Denisovan admixture.

The only reasonable way I see to reconcile 1 and 2 is to suggest that initially Sahul was settled by by early humans that were already in SEA by ~70 ky, (I would call them “middle Paleolithic “). Later wave of UP humans that came after 45 ky, likely from Siberia, and replaced uniparental lines of early settlers and brought Neanderthal admixture, but some genetic traces of early people remained (reflected in coalescence time anomaly).