Rock art may be far older than modern humans in Sulawesi

Dating of a panel with two handprints puts their production sometime before 68,000 years ago.

Yesterday I was talking with the Jakarta Post about how exciting I find the ongoing archaeological discoveries from Indonesia. The occasion of the interview was the new research on rock art from southeastern Sulawesi, the oldest dating back to more than 68,000 years ago.

The new work is the latest revelation from a program of rock art dating that has been underway for more than a decade. The paintings themselves, within caves and on rock walls in several parts of Indonesia, are not new discoveries. Many are already well-trafficked tourist sites, known and studied by Indonesian scholars for decades. What is new is the chemical analysis of small calcite formations that formed on top of some of the painted surfaces. These samples enable archaeologists to determine a minimum age for the art, integrating the pictorial record within the chronology of human arrival and activity in this region.

I wrote about the archaeological record of Sulawesi just last week. Work in Leang Bulu Bettue in southwestern Sulawesi shows an unchanged pattern of toolmaking extending from more than 130,000 up to 40,000 years ago, when a new tradition arrived. That age seems out of phase with the earliest-known rock art in the area, estimated to be more than 51,000 years old. The mismatch, I wrote, needs an explanation.

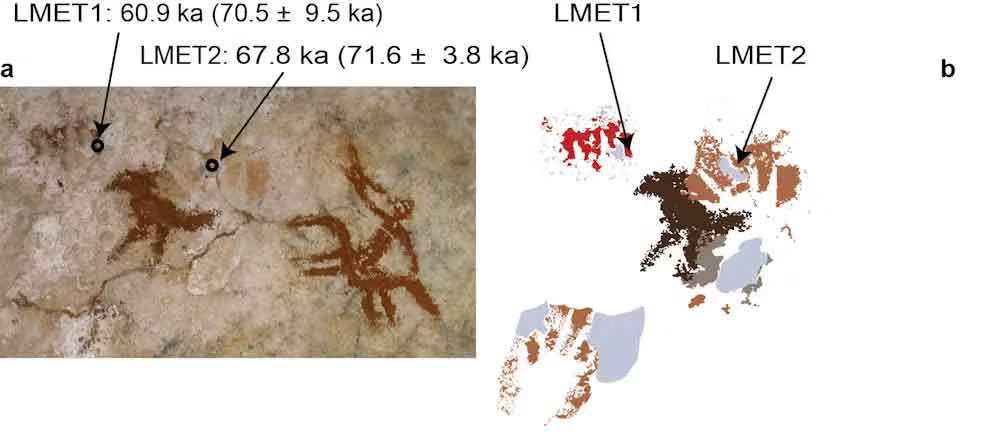

The new work by Adhi Agus Oktaviana pushes the earliest rock art back by an additional 17,000 years. The oldest panel is from Liang Metanduno, on the small island of Muna. Among a vast array of artworks dating to the last few thousand years, Oktaviana noticed two faint handprints, seemingly behind other more recent brightly-painted figures. Those two handprints generated dates averaging 71,000 years ago—the error bar of one going down to 67,800 years.

That’s 28,000 years or more before any known change in local stone tools.

On the face of things, I’d say the data suggest that the early hominin occupants of the island, possibly Denisovans, were marking their landscapes.

Some authors working on rock art suggest that the art itself is evidence for modern human presence. According to this line of thinking, rock art could not have been made by any other population of hominin. It is uniquely modern.

I don’t agree. Traditions of marking are widespread among Pleistocene hominins. In a network of interactions across islands and between hominin groups, I expect that the transfer of knowledge and traditions may have taken some surprising paths.

How rock art dating works

To carry out this new study, Adhi Agus Oktaviana and a large team of collaborators surveyed rock art sites and took small samples of calcite that they found overlaying some parts of the paintings. In the lab, they prepared thin sections of the calcite and sampled thin layers, for each one developing a series of measurements of uranium and thorium, one of the decay products of uranium. The age of the layer closest to the painting is a minimum age for the painting itself.

“During my fieldwork, I noticed faint, weathered hand stencils underlying these later motifs. Their condition and placement suggested a much earlier origin.”—Adhi Agus Oktaviana

Nature has a nice short commentary that accompanies the research article, which includes a couple of paragraphs from the lead author telling the story of the find.

A common criticism of this kind of work is that the uranium within a layer of calcite may be affected by later events. Groundwater carries uranium and leaves it within the calcite formation, which is how it gets there in the first place. When uranium atoms decay, the resulting thorium remains in the calcite. But later dripping or atmospheric water can leach the uranium out. If the uranium content is removed while the thorium remains, the resulting dates will be overestimates of the true age of the calcite.

This doesn’t necessarily overstate the age of the underlying painting. Even in the ideal case the calcite formed after the pigments were applied. But such leaching removes the logic for the calcite being a minimum age.

Throughout several publications using this methodology, the lead investigator Maxime Aubert and team have argued that the leaching of uranium can be ruled out. The main approach to detect such leaching is the dating of thin calcite layers in a sequence. Leaching from the outside would deplete the uranium in the layers furthest from the painting, resulting in an inversion of the ages. That isn’t seen in the Liang Metanduno hand stencils or in any of the other early art.

I would add that the broader picture of dating of Pleistocene art in the region, including examples in Borneo and Sulawesi, shows that there are many, many examples older than 30,000 years. A date of 68,000 years may seem like an outlier at the moment, but beyond island Southeast Asia that age is comparable to estimates for pigment markings in caves in Spain such as Maltravieso, Ardales, and La Pasiega, where marks were likely created by Neanderthals.

Who made the marks?

For me the null hypothesis is that the marks were made by the archaic hominins known to have been on the island at the time. The archaeological record of Sulawesi thus far offers no evidence of cultural changes that would point to an influx of newcomers until around 40,000 years ago.

In their paper, Oktaviana and coworkers suggest that modern humans made the handprints. Their logic is that the art itself is evidence of newcomers. They further suggest a possible stylistic link between the handprints in Liang Metanduno and some sites with later ages.

Could it be that these marks and other later painted figures, such as the 51,000+ year-old paintings from Leang Karampuang, were made by modern island-hoppers on their way to Australia?

I think it’s just as likely that the handprints were made by Denisovan coastline-adapted people whose relatives were already making their homes in coastal Sahul by this time. The notion that there was uniquely one dispersal of humans across eastern Indonesia requires a bunch of assumptions that I wouldn’t make. Instead, I think the genetic and archaeological data may be best explained by a network of interactions with multiple pathways for introgression and mixture.

For readers in Europe, my understanding is that the Arte television channel will be broadcasting a documentary on the Sulawesi rock art finds in conjunction with the paper’s publication today. The channel has posted a few clips on YouTube that are available to viewers outside Europe. I’ve embedded one here that shows the research team in Liang Metanduno, with Adhi Oktaviana pointing to the faint handprints.

It’s a truly remarkable finding, and with such a regional tradition of art, I am sure there will be many more dates to flesh out the true antiquity of this tradition and its makers.

Notes: The first habitation of Australia is a tough topic to write about because of the scope of evidence that is part of recent debates. The newsroom version of this topic doesn’t get into the kinds of details that are really at issue, and different research groups have built very different concepts of how the archaeological findings relate to movements of modern humans and others. As I write more about this topic, I’ll try to flag some of the points of agreement and disagreement that have featured in the published research.

Meanwhile, here are links to some of the key recent posts that cover research from this part of the world.

References

Aubert, M., Brumm, A., Oktaviana, A., & Joannes-Boyau, R. (2026). Humanity’s oldest known cave art has been discovered in Sulawesi. The Conversation. https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.j4xujax6w

Aubert, M., Brumm, A., Ramli, M., Sutikna, T., Saptomo, E. W., Hakim, B., Morwood, M. J., Van Den Bergh, G. D., Kinsley, L., & Dosseto, A. (2014). Pleistocene cave art from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Nature, 514(7521), 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13422

Brumm, A., Langley, M. C., Moore, M. W., Hakim, B., Ramli, M., Sumantri, I., Burhan, B., Saiful, A. M., Siagian, L., Suryatman, Sardi, R., Jusdi, A., Abdullah, Mubarak, A. P., Hasliana, Hasrianti, Oktaviana, A. A., Adhityatama, S., Van Den Bergh, G. D., … Grün, R. (2017). Early human symbolic behavior in the Late Pleistocene of Wallacea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(16), 4105–4110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619013114

Brumm, A., Oktaviana, A. A., Burhan, B., Hakim, B., Lebe, R., Zhao, J., Sulistyarto, P. H., Ririmasse, M., Adhityatama, S., Sumantri, I., & Aubert, M. (2021). Oldest cave art found in Sulawesi. Science Advances, 7(3), eabd4648. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4648

Oktaviana, A. A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B., Burhan, B., Sardi, R., Adhityatama, S., Hamrullah, Sumantri, I., Tang, M., Lebe, R., Ilyas, I., Abbas, A., Jusdi, A., Mahardian, D. E., Noerwidi, S., Ririmasse, M. N. R., Mahmud, I., Duli, A., Aksa, L. M., … Aubert, M. (2024). Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature, 631(8022), 814–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07541-7

Westaway, K. E., Louys, J., Awe, R. D., Morwood, M. J., Price, G. J., Zhao, J. -x, Aubert, M., Joannes-Boyau, R., Smith, T. M., Skinner, M. M., Compton, T., Bailey, R. M., van den Bergh, G. D., de Vos, J., Pike, A. W. G., Stringer, C., Saptomo, E. W., Rizal, Y., Zaim, J., … Sulistyanto, B. (2017). An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73,000–63,000 years ago. Nature, 548(7667), 322–325. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23452

White, R., Bosinski, G., Bourrillon, R., Clottes, J., Conkey, M. W., Rodriguez, S. C., Cortés-Sánchez, M., de la Rasilla Vives, M., Delluc, B., Delluc, G., Feruglio, V., Floss, H., Foucher, P., Fritz, C., Fuentes, O., Garate, D., González Gómez, J., González-Morales, M. R., González-Pumariega Solis, M., … Willis, M. D. (2020). Still no archaeological evidence that Neanderthals created Iberian cave art. Journal of Human Evolution, 144, 102640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102640

Great insight! Would the continuity of material culture from 130,000 to 40,000 years ago disfavor a hypothesis that the art was made by an earlier Out of Africa, or pre-OOA, homo sapien population?