Top 10 discoveries about ancient people from DNA in 2025

In a year full of Denisovan discoveries, I look at some of the top highlights of research.

It was the year of the Denisovan. We learned at last what they looked like, detected one that was dredged from the seafloor, and saw a new tooth become the oldest-ever high-coverage genome.

In this field of study, what seems outside the realm of technology today can come surprisingly fast into focus. That’s why it’s always fun to look back at the year’s research and point to what’s new.

One trope of ancient DNA research is the “previously-unknown lineage”, and as usual there were some new ones this year. On the list I’ve included two at opposite ends of the great dispersal of humans from Africa.

Meanwhile, new ways of looking at data from genomes often help illuminate new questions. I’ve thrown in a couple of stories about function, one focused on the expression of genes that may differ in 3D organization across populations, another on minor components of diet that may have major effects.

Finally, the ethical landscape of genetic research has continued to mature. As I reflected in last year’s review, the best practices for research on human remains include leadership and consultation from descendants of the groups being studied. A valuable example of that kind of research from the American Southwest has a place on this year’s list.

Recognizing the Longren

I don’t see how anybody is supposed to compete for top ancient DNA stories this year with Qiaomei Fu.

The biggest mystery in paleoanthropology was set up 15 years ago with the discovery that an 80,000-year-old finger bone from Denisova Cave, Russia wasn’t who anyone thought it would be. In June, Fu’s research team finally put a face to the enigmatic group known as Denisovans, connecting the mitochondrial genome and proteome of the 146,000+ year old Harbin skull to the group.

The Harbin skull was named Homo longi by Qiang Ji and coworkers after its discovery, and has commonly been called Longren, or “Dragon Man” by the press and other researchers. The skull looks a lot like some other Middle Pleistocene fossils from China, including the Dali skull, which means one Denisovan mystery is solved.

These were not the only interesting Denisova-related stories this year. In April Takumi Tsutaya and colleagues reported on proteomic data from a jaw recovered from the seafloor of the Penghu Strait, showing it to have been a male individual within the broader Denisovan population.

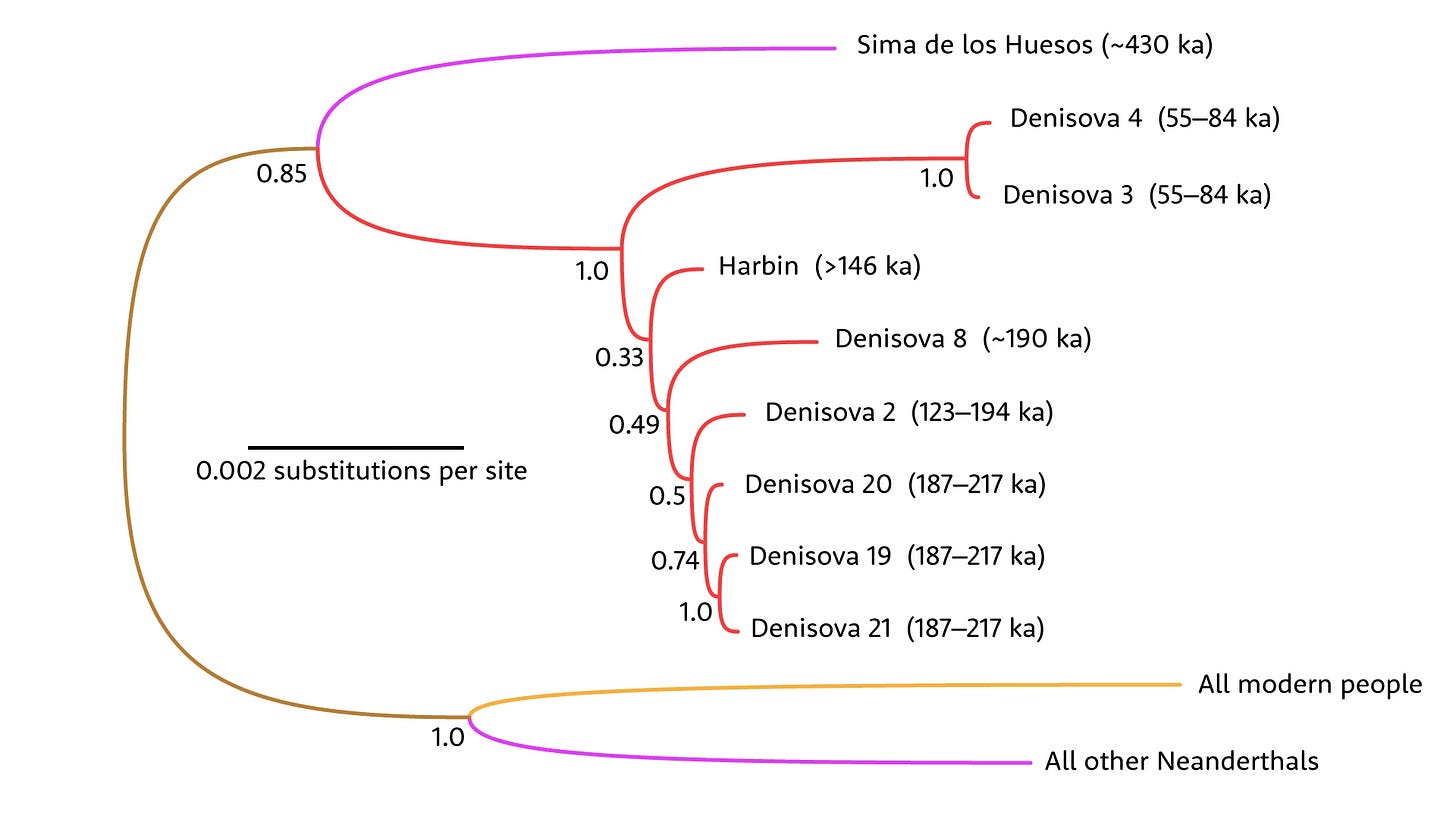

Oldest high-coverage genome

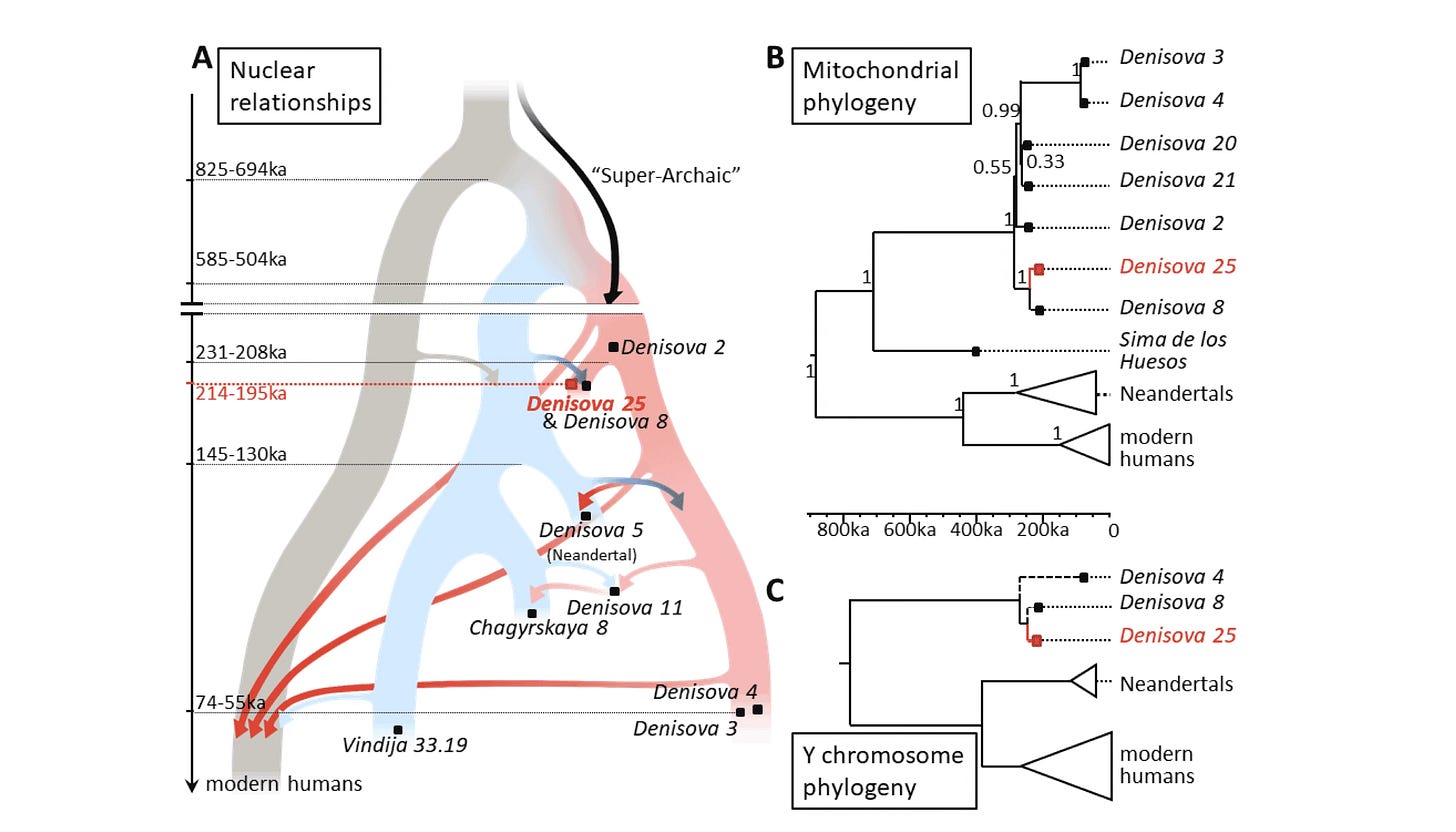

Tripling down on Denisovans has not usually been my approach in these year-end lists. But in October, Stéphane Peyrégne and coworkers released a high-coverage genome from the molar tooth designated as Denisova 25, roughly 200,000 years old. It’s the oldest high-coverage genome yet reported.

Adding even one early data point like this makes a surprisingly big difference to some findings. For example, a model including the new genome suggests that African ancestors of modern people diverged from Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors between 825,000 and 694,000 years ago—maybe 50,000 to 100,000 years earlier than the previous estimate.

Meanwhile, Denisova 3 and the hybrid Denisova 16 both already showed that mixture between these groups and Neanderthals was happening a lot. Denisova 25 adds a deeper time dimension to this mixture, from even earlier Neanderthal groups. The genome also confirms the ancient passage of “superarchaic” ancestry into the early Denisovans.

There’s a lot in this analysis to add detail to the mixture of Denisovans and modern people, including the observation that estimated admixture fraction goes up when the second Denisovan genome is added to analyses. There is a lot on the functional variation of Denisovan genomes, also. This is a study that I’ll be returning to over the next year.

Debunking Pompeii fantasies

Pompeii is possibly the world’s most famous archaeological site. It is certainly one of the oldest to be visited by the public. In 1863 Giuseppe Fiorelli, who was directing the excavations, recognized that hollow cavities in the hardened volcanic ash were negative molds of human bodies. He poured in plaster of Paris, waited for it to harden, and continued the excavation, exposing the plaster casts of the ancient people.

Enabling visitors to see the victims of Vesuvius at the times of their deaths was an immediate sensation. Today the plaster casts number more than 100 across the site. Over the years, stories arose about some of the figures. For instance, in the House of the Golden Bracelet, an adult wearing a golden bracelet with a child on their lap was long suspected to be a mother and her child. Other individuals found in the same house were assumed to be part of the family group.

Last year, Elena Pilli and coworkers carried out genetic analysis of bone from 14 out of 86 plaster casts that were undergoing restoration. Five preserved DNA sufficient for examining ancestry and relatedness.

Even with just this handful of individuals, the results showed that some longstanding stories were fiction. The “mother” with the golden bracelet was actually male; the child was unrelated. None of four people in the house were genetically related.

Two individuals found in the House of the Cryptoporticus ended their lives one touching the other, long interpreted as sisters in an embrace. But DNA from one of the individuals shows that he was male.

Pilli and coworkers end their study noting that narratives from such limited data are unreliable. One problem has been projecting modern assumptions about gendered behaviors and kinship onto ancient groups, where different cultural expectations were at play. Another is the temptation by previous generations of researchers to manipulate poses or otherwise emphasize some aspects of the evidence.

Marriages of the Avars

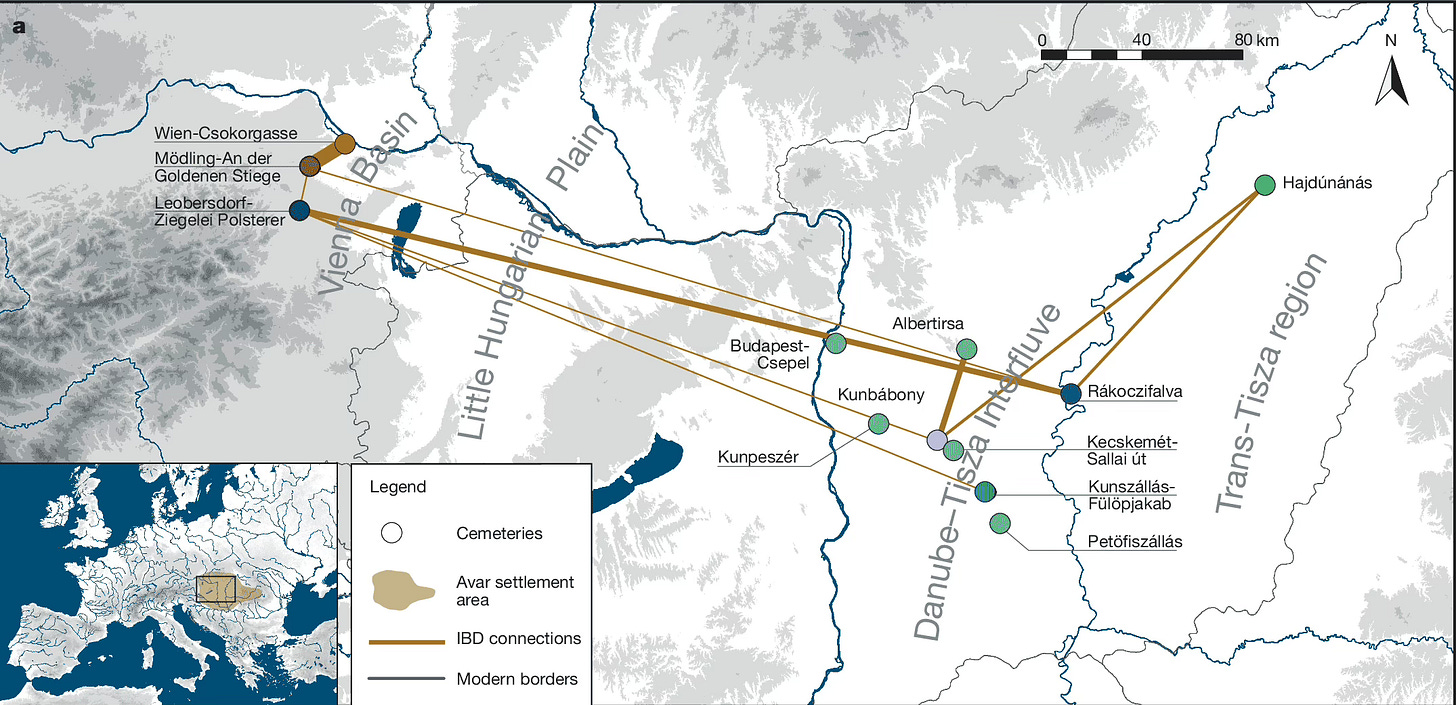

One of the most valuable uses of ancient DNA is to help understand how culture and genealogy are related. When people move en masse from one place to another, carrying their culture with them, the appearance of new culture and new genealogical lineages may be easily apparent. But it has been more challenging to see the genealogical effects of trade and interchange between established population centers. That kind of analysis has become possible with evidence of genealogical relatives from distant sites.

A well-designed study in January by Ke Wang and collaborators looked at two cemeteries from the late Avar period near Vienna, dating to the seventh century or eighth century CE. The Avars originated as steppe peoples before settling in central Europe north of East Roman provinces in the Balkans. Wang and coworkers sampled almost every skeleton from the Late Avar period from both cemeteries: Leobersdorf with 155 individuals and Mödling-An der Goldenen Stiege with 485 individuals. They added 83 from the nearby Csokorgasse cemetery, working to construct genealogies connecting individuals with each other.

All of these cemeteries lie within 20 km of each other and represent culturally similar peoples who lived at the same time, with the same burial practices and artifacts reflecting social status. So it is surprising that there is little genetic similarity between the Leobersdorf people, who derive most of their ancestry from eastern Eurasia, and the Mödling burials, which look like other nearby central Europeans.

Especially striking are the many instances of close genealogical relatives that Wang and coworkers could identify between Leobersdorf people and other cemetery sites hundreds of kilometers to the east, on the Hungarian plain. For Mödling, there were hardly any—instead, there were quite a few genealogical relatives in the nearby Csokorgasse cemetery.

As the authors note, the Leobersdorf people of this period seem to have sought out specific groups for marriages, focusing on the Avar heartland. For the Mödling people, the story was different. Two groups with such different patterns of intermarriage, yet within a common cultural setting: that’s something that we see today in many places, but can be almost invisible in the past. This is a remarkable case study.

Green Sahara

The Sahara Desert today covers more than seven million square kilometers, almost the land area of Australia. Much of the desert is inhabited very sparsely by groups of herders such as the Bedouin and Tuareg, with a few large population centers at oases where water can be found.

Between 15,000 and 5,000 years ago things were different. The central Sahara had shallow lakes and streams, well-watered grassland and brushland. This time is known as the African Humid Period.

This year, research from Nada Salem and collaborators drew attention to the people who flourished in this green Sahara. They obtained genomes from two individuals excavated from the Takarkori rock shelter in extreme southwest Libya, with radiocarbon ages between roughly 7000 and 6000 years ago. There, in the in the Tadrart Acacus Mountains, people herded cattle, sheep and goats. The running water in the nearby Wadi Takarkori enabled the people to continue a mixed economy with hunting and fishing. Abundant rock art depicts a vibrant society.

Salem and coworkers found that a deep, previously-unrecognized lineage makes up most of the ancestry of the Takarkori individuals. This deep ancestry shares a common stem with the founder group that dispersed from Africa into Eurasia more than 50,000 years ago. Identifying this deep lineage helped the researchers reinterpret findings from the 15,000-year-old genomes of people from Taforalt, Morocco. These people, representing the Iberomaurusian culture of hunter-gatherers, shared a connection with the Takarkori genomes, suggesting how widespread this lineage was through the later Pleistocene.

The research helps to provide context for the introduction of pastoral ways of life into North Africa. The idea of herding animals may have come from southwest Asia with the domesticated breeds themselves, but gene flow from earlier Levantine peoples did not make a major impact at Takarkori.

Finding unexpected genetic lineages has been a common occurrence in the ancient DNA era. For me, this one is especially interesting because it helps ground the out-of-Africa founders in Northeast Africa. Some archaeologists have long held that cycles of population growth and dispersal in a green Sahara were important to the eventual dispersals of modern humans into Eurasia. The Takarkori findings show that the greening of the desert did not pull much gene flow either from the south nor back into Africa from the Levant. The staging area for the dispersal may have been the Sahara itself.

Selection for micronutrients

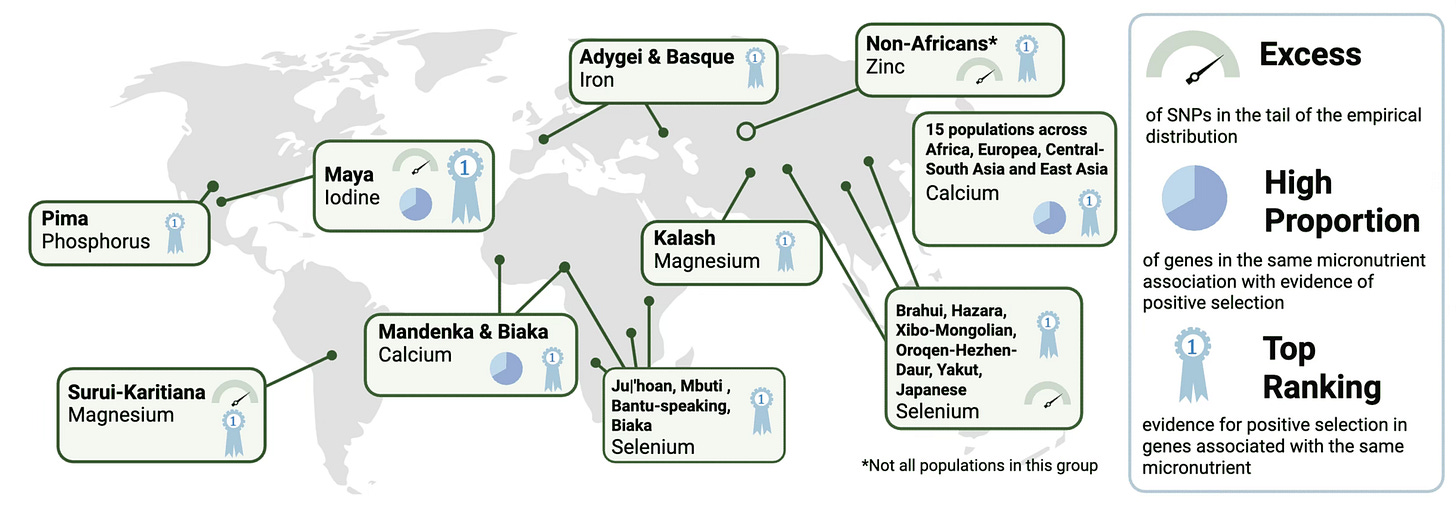

One of the most important factors in recent human evolution has been diet. Agricultural processes have shifted nutrient availability, so that calories come much more from high-carbohydrate grains, alcohol, and milk, for example. Less obvious are shifts in minerals like selenium and zinc, ultimately determined by their abundance in soils and local plants. But such micronutrients have impacts on health, and some human genes make a difference to how people’s bodies take in and process them.

In October, Jasmin Rees, Sergi Castellano, and Aida Andrés published a synthesis of how micronutrients have mattered to natural selection around the world. They identify several cases of local adaptation, some occurring in parallel in different groups.

For example, both Maya people and Mbuti hunter-gatherers live in iodine-deficient environments, and both have candidate gene sets that may reflect adaptation to low iodine. In East Asia, populations like the Yakut and Japanese show significant evidence of adaptation to selenium-deficient soils.

Many of these signals are made up of variants from several genes, a pattern of change called oligogenic adaptation—meaning that anywhere from three to ten genes may act together with fairly large effects on the trait. This evolutionary pattern may be especially relevant for humans moving into new regions and encountering new environments—seen in other contexts with pigmentation, adaptation to high altitude, and immunity.

Ancient genomes in 3D

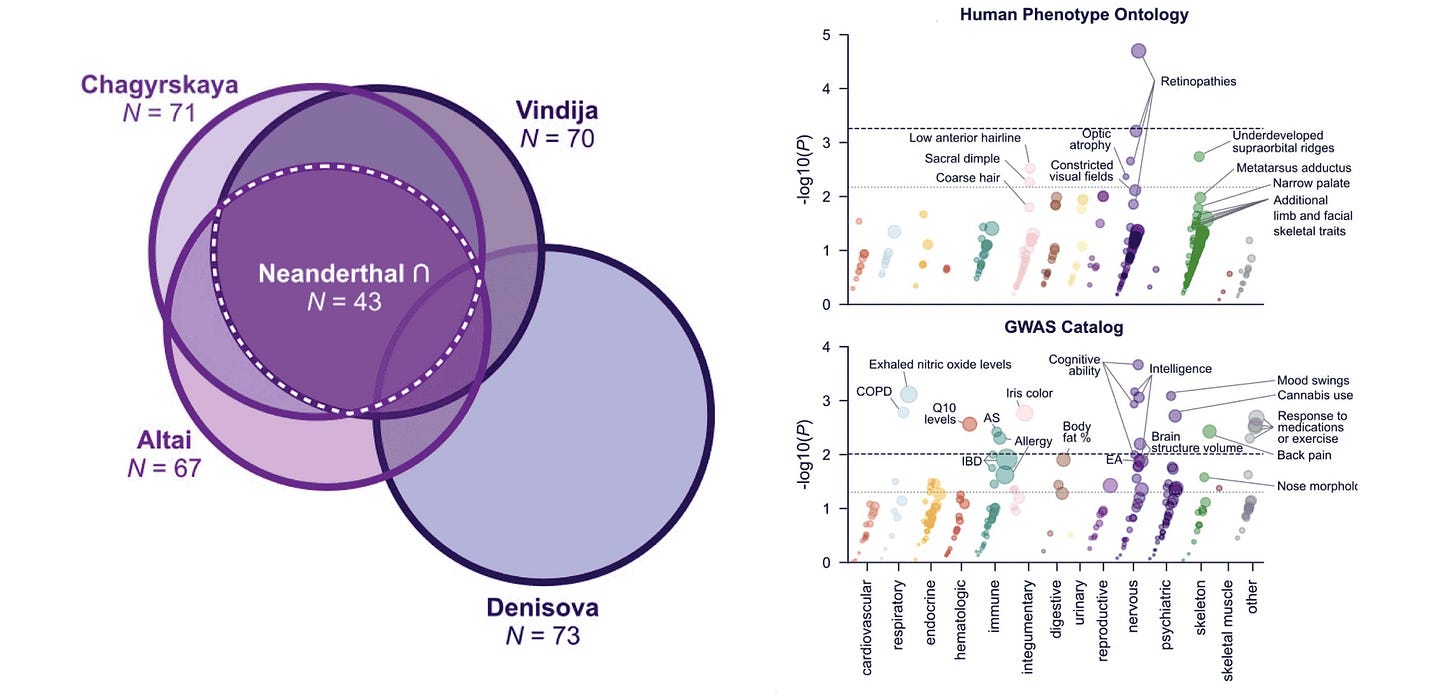

People living today have some clear differences in skeletal and dental form from Neanderthals and Denisovans. Tracking down the genetic correlates of those phenotypic differences has been a challenge. An early focus of research was amino-acid-coding differences, but there are surprisingly few of these between living people and the archaic genomes. Many researchers have pointed to the idea that it’s not protein-coding variation that drove the evolution of modern people, it’s how genes are regulated—focusing on regulatory sites and methylation as ways of understanding gene expression.

A growing area of research is the three-dimensional configuration of the genome. Genes are regulated in part by the physical proximity of sequence motifs after DNA-containing chromatin has been folded and looped into 3D shapes. In a preprint updated in September, Evonne McArthur and coworkers report on advances in understanding 3D genome organization in Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes.

What they find is fascinating. They identify between 60 and 75 parts of the genome in archaic human data where the archaic sequence exhibits high 3D genome organization divergence from all modern samples. That’s not a lot. Still, a pass across these areas in gene function datasets provides some interesting hits: Eye function, brain, skin and hair, and some skeletal traits.

The 3D genome organization may be a key to understanding some of the introgression of Neanderthal genes into recent people. McArthur and colleagues show that areas of the genome with high 3D variability in today’s people are also more likely to have introgressed variants, while areas with large differences in 3D organization between Neanderthal and modern genomes are less likely to have introgression. They also show some places where introgression has brought the pattern of 3D genome organization of some Eurasian individuals into a Neanderthal-like configuration.

Filling in the southern cone

The last decade has seen some large-scale syntheses of the dispersal of humans into the Americas. At a smaller scale, researchers have been investigating DNA records of particular regions. This year, Javier Maravell-López and collaborators reported in more than 200 ancient genomes from the Paraná River to the Andes Mountains, and across twenty degrees of latitude, from northern Paraguay to Bahía Blanca.

The people of this region developed a distinctive genetic lineage very soon after first arriving. An ancient genome from around 10,000 years ago already has a pattern of genetic drift distinguishing the individual from other groups around South America, and shared with later people from the same region.

That identity remained strong over time as groups of this area mixed with nearby regions. At the northwest extreme of the study area, ancient people mixed with populations of the central Andes, including Tiwanaku and related groups. In the south, they encountered the descendants of another fast-diverging group, expanding into their range in the Pampas region.

It’s easy to underestimate the vast land spaces of South America. Headlines this year flashed that an unknown lineage remained isolated for 8000 years. That’s not actually what the study says. What happened was fast growth followed by diffusion of people into and out of the region. Understanding that pattern may take us a long way toward the ancestral population structure across both Eurasia and the Americas.

Ancestral Puebloans

Many Indigenous people of the U.S. are deeply interested in what genetics can reveal about genealogy and history, but are deservedly wary. Archaeologists built up a bad track record across almost two centuries, often ignoring Indigenous histories, digging into sacred sites, and hauling ancestors away to museums. But across the last twenty years, many researchers who focus on ancient DNA have built stronger relationships with tribes. These relationships have led to better science and a stronger trust for research into the past.

This year provides a great example of research co-developed with Indigenous people. Eske Willerslev’s Copenhagen-based research team worked together with people from Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico, to focus on the ancestry of today’s community members and their connections to Ancestral Puebloans. A crucial aspect of the research involved a commitment to ensure data sovereignty for Picuris Pueblo throughout the collaboration.

By sampling both living members and ancient individuals from the last millennium, the study provides a strong picture of a large, diverse group prior to European presence in the region. The data also show a strong connection between Picuris people and Ancestral Puebloan people who lived in Chaco Canyon, around 250 km to the west. This part of the study reinforces oral histories that have been held by Picuris people and by other groups.

The work may also show how community-led research can help repair relationships that were broken by earlier researchers, including both archaeologists and geneticists. Work on DNA from Chaco Canyon published in 2017 became one of several high-profile instances where researchers pushed into ancient DNA sequencing without any consultation with descendant communities.

It is widely recognized within anthropology and human genetics that working with potential descendants leads to better, more accurate scientific results. That outcome can be seen in the new Picuris study, where the participation of the community has added greatly to understanding of the genetic results.

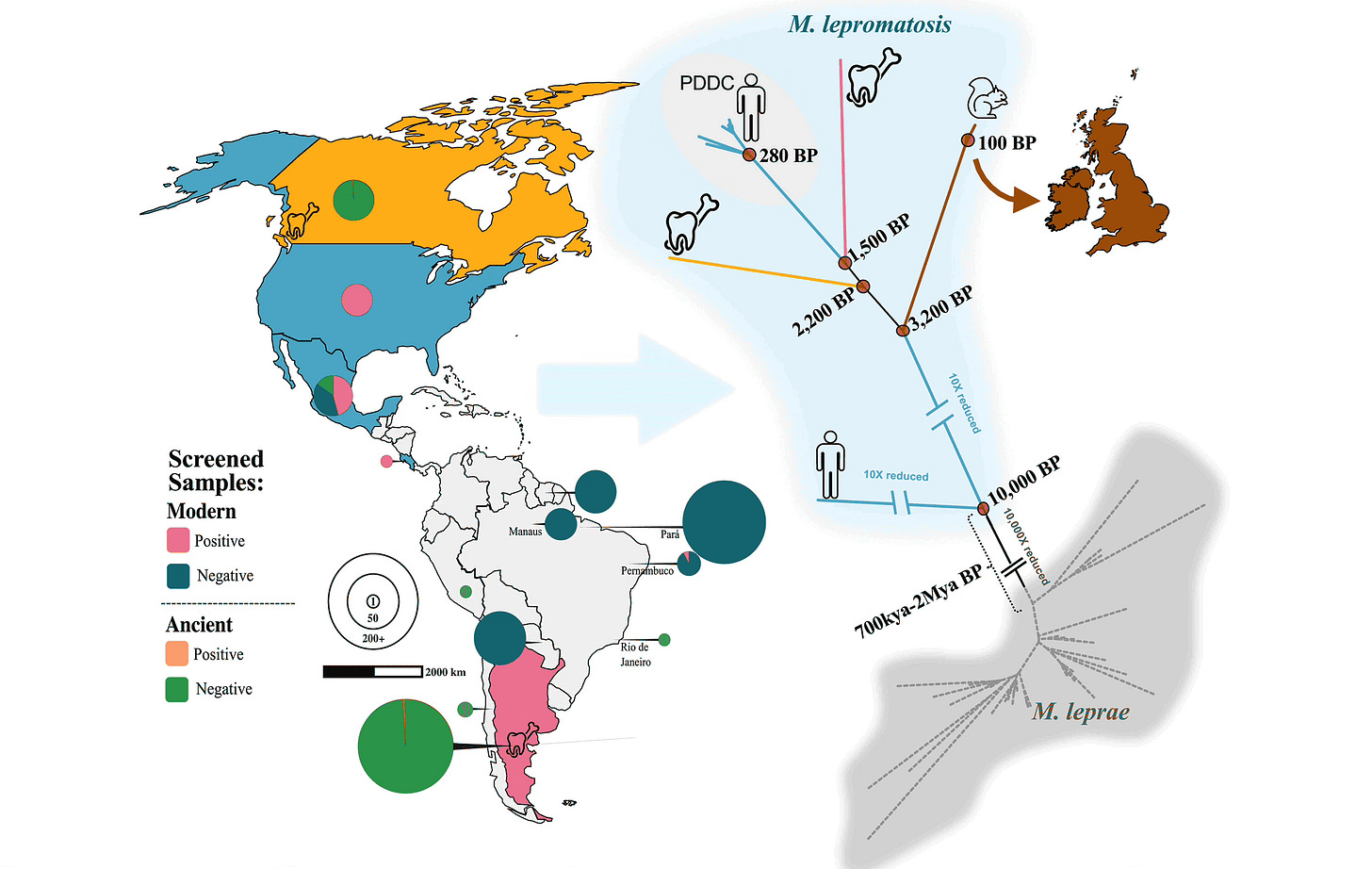

The other leprosy

One of my favorite stories of the year concerns an infectious agent of Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy. Until 2008, scientists thought that this global malady was always caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. Then a second pathogen was identified: Mycobacterium lepromatosis. It was first seen in the Americas, and later a few human cases were noted in Eurasia. Then, researchers found it in some of the lesions affecting red squirrels in Britain.

Was it an emerging pathogen, or a neglected one? In May, a massive study led by Maria Lopopolo reported on large-scale screening of bacterial genomes from more than 400 living patients, and 389 ancient genomes across the Americas.

They found M. lepromatosis in 34 living cases, mostly in the U.S. and Mexico. They also found three ancient genomes with the bacterium: one from Canada and two from Argentina, all from the period before European contact. This shows the presence of M. lepromatosis infection was widespread in the ancient peoples of the Americas.

To me the most fascinating element of the study is the estimation of the ancestral divergence between M. lepromatosis and M. leprae, with two models pointing to different dates: around 795,000 to 660,000 years ago, or alternatively between 2.5 and 1.5 million years ago. Either of these sets of dates would imply a passage of the ancestors of one clade from Eurasia to the Americas, or vice-versa.

Red squirrel cases of M. lepromatosis, possibly acquired after gray squirrels were introduced from North America into Britain, may point to the possibility that a nonhuman mammal host carried the pathogen across Beringia, where ancient Americans encountered it. But the obvious species to have dispersed M. lepromatosis in ancient times is humanity itself. It’s interesting to consider whether ancient humans may have contracted Hansen’s disease from earlier contacts with Denisovans or other hominins.

A look forward

Large-scale research teams have filled out many regions of the world with ancient genomes. Africa and southern Asia remain obvious outliers, where studies of a single genome can still make a big difference. Among the stories I didn’t include from this year: a study based on a single genome from Old Kingdom Egypt, as well as a study of a couple dozen ancient genomes from South Africa. I expect in the next few years that advancing technical methods will unleash new datasets from these regions.

Meanwhile, in Europe, China, and parts of the Americas, the state of the art has moved toward investigating cultural and social practices with genealogical genomics. What matters to these questions is not only regional ancestry but the pattern of genealogical connections between people. The studies of the Avar and Pompeii remains are examples of this kind of research from 2025. Investigation of more broad-scale aspects of kinship were also important in the Argentina ancient DNA study

Last year I pointed to the advancing work on ancient pathogens, which has continued to accelerate. This was a year of consolidation of some old results—like the many studies of bubonic plague from ancient sites. Researchers have also published a number of meta-analyses and reviews, starting to bring together the big epidemiological picture. The area is ripe for a new synthesis.

It’s paleoenvironmental analysis with DNA where I’m expecting some big innovation in the next year. Sediment DNA has extended the knowledge that can be brought from animal, plant, and microbial remains. A massive study of subsistence at Denisova Cave this year, a study of human-carnivore interactions from El Mirón Cave in Spain, and a look at ancient wolf, bison, and human DNA from Satsurblia Cave, Georgia, are all recent examples of this kind of work.

What will be next? We’ll see in 2026!

Notes: Several articles have looked closely at the genetic research on Pueblo Bonito individuals and their implications for tribal consultation and repatriation. I can suggest the works I’ve cited below led by Katrina Claw, and by Amanda Daniela Cortez.

There were some amazing DNA studies that I wrote about during the year and didn’t repeat for this post. Think of them as a bonus! A standout was the study of the MUC19 gene by Fernando Villanea and coworkers. Another excellent study was the work on Papuan adaptations with a focus on immunity. And there was the interesting study of lactase persistence genetics in China, with a Neanderthal haplotype implicated.

References

Fu, Q., Bai, F., Rao, H., Chen, S., Ji, Y., Liu, A., Bennett, E. A., Liu, F., & Ji, Q. (2025a). The proteome of the late Middle Pleistocene Harbin individual. Science, 0(0), eadu9677. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu9677

Fu, Q., Cao, P., Dai, Q., Bennett, E. A., Feng, X., Yang, M. A., Ping, W., Pääbo, S., & Ji, Q. (2025b). Denisovan mitochondrial DNA from dental calculus of the >146,000-year-old Harbin cranium. Cell, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.040

Claw, K. G., Lippert, D., Bardill, J., Cordova, A., Fox, K., Yracheta, J. M., Bader, A. C., Bolnick, D. A., Malhi, R. S., TallBear, K., & Garrison, N. A. (2017). Chaco Canyon Dig Unearths Ethical Concerns. Human Biology, 89(3), 177. https://doi.org/10.13110/humanbiology.89.3.01

Cortez, A. D., Bolnick, D. A., Nicholas, G., Bardill, J., & Colwell, C. (2021). An ethical crisis in ancient DNA research: Insights from the Chaco Canyon controversy as a case study. Journal of Social Archaeology, 21(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605321991600

Lopopolo, M., Avanzi, C., Duchene, S., Luisi, P., De Flamingh, A., Ponce-Soto, G. Y., Tressieres, G., Neumeyer, S., Lemoine, F., Nelson, E. A., Iraeta-Orbegozo, M., Cybulski, J. S., Mitchell, J., Marks, V. T., Adams, L. B., Lindo, J., DeGiorgio, M., Ortiz, N., Wiens, C., … Rascovan, N. (2025). Pre-European contact leprosy in the Americas and its current persistence. Science, 389(6758), eadu7144. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu7144

McArthur, E., Rinker, D. C., Cheng, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, J., Gilbertson, E. N., Fudenberg, G., Pittman, M., Keough, K., Yue, F., Pollard, K. S., & Capra, J. A. (2025). Reconstructing the 3D genome organization of Neanderthals reveals that chromatin folding shaped phenotypic and sequence divergence. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.07.479462

Peyrégne, S., Massilani, D., Swiel, Y., Boyle, M. J., Iasi, L. N. M., Sümer, A. P., Mesa, A. B., De Filippo, C., Viola, B., Essel, E., Nagel, S., Richter, J., Weihmann, A., Schellbach, B., Zeberg, H., Visagie, J., Kozlikin, M. B., Shunkov, M. V., Derevianko, A. P., … Kelso, J. (2025). A high-coverage genome from a 200,000-year-old Denisovan. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.20.683404

Pilli, E., Vai, S., Moses, V. C., Morelli, S., Lari, M., Modi, A., Diroma, M. A., Amoretti, V., Zuchtriegel, G., Osanna, M., Kennett, D. J., George, R. J., Krigbaum, J., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Caramelli, D., Reich, D., & Mittnik, A. (2024). Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts. Current Biology, 34(22), 5307-5318.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.007

Pinotti, T., Adler, M. A., Mermejo, R., Bitz-Thorsen, J., McColl, H., Scorrano, G., Feizabadifarahani, M., Gandy, D., Boulanger, M., Gaunitz, C., Stenderup, J., Ramsøe, A., Korneliussen, T., Demeter, F., Santos, F. R., Vinner, L., Sikora, M., Meltzer, D. J., Moreno-Mayar, J. V., … Willerslev, E. (2025). Picuris Pueblo oral history and genomics reveal continuity in US Southwest. Nature, 642(8066), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08791-9

Ramirez, D. A., Sitter, T. L., Översti, S., Herrera-Soto, M. J., Pastor, N., Fontana-Silva, O. E., Kirkpatrick, C. L., Castelleti-Dellepiane, J., Nores, R., & Bos, K. I. (2025). 4,000-year-old Mycobacterium lepromatosis genomes from Chile reveal long establishment of Hansen’s disease in the Americas. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 9(9), 1685–1693. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02771-y

Rees, J., Castellano, S., & Andrés, A. M. (2025). Global impact of micronutrients in modern human evolution. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 112(10), 2538–2561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2025.08.005

Salem, N., van de Loosdrecht, M. S., Sümer, A. P., Vai, S., Hübner, A., Peter, B., Bianco, R. A., Lari, M., Modi, A., Al-Faloos, M. F. M., Turjman, M., Bouzouggar, A., Tafuri, M. A., Manzi, G., Rotunno, R., Prüfer, K., Ringbauer, H., Caramelli, D., di Lernia, S., & Krause, J. (2025). Ancient DNA from the Green Sahara reveals ancestral North African lineage. Nature, 641(8061), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08793-7

Tsutaya, T., Sawafuji, R., Taurozzi, A. J., Fagernäs, Z., Patramanis, I., Troché, G., Mackie, M., Gakuhari, T., Oota, H., Tsai, C.-H., Olsen, J. V., Kaifu, Y., Chang, C.-H., Cappellini, E., & Welker, F. (2025). A male Denisovan mandible from Pleistocene Taiwan. Science, 388(6743), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ads3888

Wang, K., Tobias, B., Pany-Kucera, D., Berner, M., Eggers, S., Gnecchi-Ruscone, G. A., Zlámalová, D., Gretzinger, J., Ingrová, P., Rohrlach, A. B., Tuke, J., Traverso, L., Klostermann, P., Koger, R., Friedrich, R., Wiltschke-Schrotta, K., Kirchengast, S., Liccardo, S., Wabnitz, S., … Hofmanová, Z. (2025). Ancient DNA reveals reproductive barrier despite shared Avar-period culture. Nature, 638(8052), 1007–1014. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08418-5